In a previous post in this series, I criticized proposals to raise the eligibility age for Social Security and Medicare. It is already getting harder to save enough for a comfortable retirement; raising the eligibility age would just make it still more difficult. In this installment, I turn to policies to encourage retirement saving, explaining why our current system is not working well and suggesting some alternatives.

Why should we make it easier to retire? Grasshoppers vs. Ants

We can start by asking why making it easy to retire should be an objective of public policy in the first place. The fable of the grasshopper and the ant is the lens through which many people view the issue. The ant works hard and saves carefully all summer, while the grasshopper sings and dances. When winter comes, the grasshopper begs for a handout. The fable portrays the ant as justified in shutting her door to him. Why should the government, as agent of the ant-like taxpayers that pay its bills, behave any differently toward grasshoppers who don’t have the self-discipline to save during their working years?

The most common response is to justify government support for retirement as a form of social insurance. Life is full of risks. For retirement saving, the relevant risks include spells of unemployment, health problems, the risk of losses or low returns on retirement savings, the risk of inflation, and last but not least, the risk of outliving one’s savings. When we take those risks into account, we understand that some people will reach retirement age without adequate savings not because they are grasshoppers, but because they are unlucky ants. Many of the risks that can thwart the best-laid plans for retirement savings are neither under the control of individuals nor privately insurable. Only the government is in a position to pool the risks broadly enough to guarantee a minimum level of retirement income for everyone.

At the same time, skeptics have a valid point when they warn against incentivizing grasshopper-like behavior. It is reasonable to want public policy to encourage people to save for their own retirement even while providing a safety net for those whose efforts fall short.

In the United States, the tension between providing a reasonable degree of social insurance and encouraging thrift has given us a two-part retirement policy that combines Social Security with tax-sheltered private retirement savings. Unfortunately, neither part is working well.

The future of social security

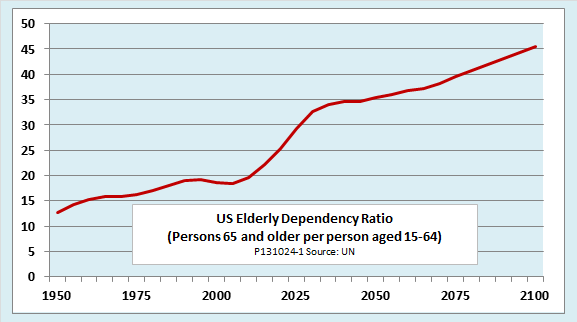

Social Security is one of the most popular government programs ever created, but it faces an uncertain future. As it stands now, Social Security is neither a real retirement savings program nor a pure social safety net. It is not a savings program in the sense that participants’ payroll taxes are not invested to fund their own retirement. Its trust fund, which consists entirely of special government bonds, is only an accounting device. What we really have is a system under which those currently working pay for those who have already retired. That worked reasonably well as long as the elderly dependency ratio was low, but it has come under strain now that the ratio is rising, as shown in the following chart.

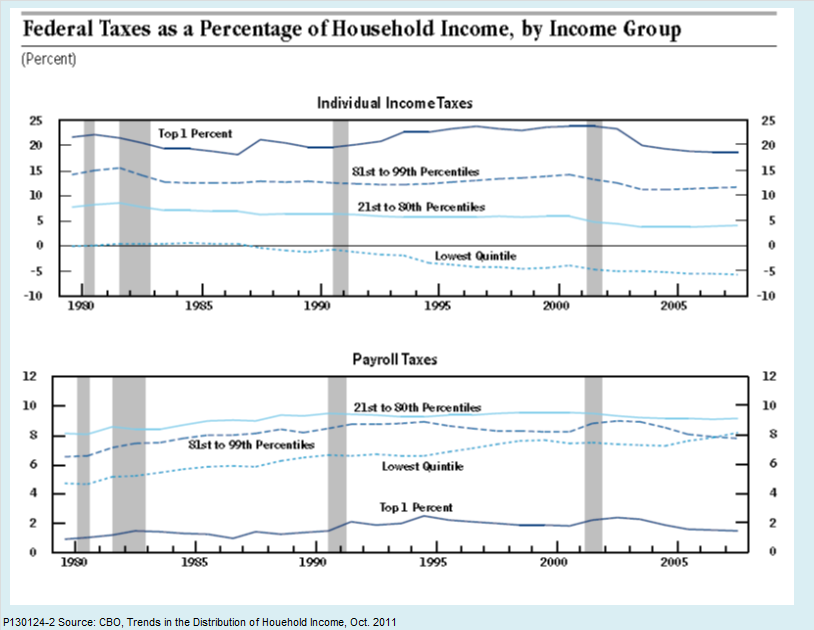

At the same time, Social Security is not a pure social safety net. People with fewer than 10 years of work usually receive no benefits. For those who have worked long enough, benefits increase with contributions. There is some progressivity built into the system since the relationship of benefits to contributions is not linear, but even so, the highest benefits tend to go to the least needy. Furthermore, the progressivity of the benefit schedule is offset to a substantial degree by the regressivity of the payroll tax that pays for the benefits. As the next chart shows, the payroll tax has been taking a steadily increasing share of the income of households in the lowest quintile of the income distribution, in contrast to the income tax, which has been taking a decreasing share.

Raising payroll taxes to meet increasing Social Security outlays no longer seems feasible. Most recent reform proposals have, instead, concentrated on reducing benefits. Raising the age of eligibility for full benefits, for reasons explained in the preceding post, would make the system more regressive. Changing the formula for calculating cost-of-living increases would gradually reduce benefits for all participants. Means testing of benefits for high-income participants would make the system more progressive. If the minimum benefit were raised by enough to bring recipients up to the poverty level at the same time that payments to higher-income beneficiaries were reduced, Social Security would start to look more like a real social safety net.

Whatever reforms are adopted, one thing is virtually certain. The trend toward increasing dependence on individual retirement savings will continue for most middle-class families.

Why tax incentives for retirement saving have failed

Today, the principal policy for encouraging retirement savings is to shelter them from taxes. Employer contributions to pension plans are subject neither to corporate nor individual income taxes. Individual contributions to 401(k) plans, Individual Retirement Accounts, and similar plans are tax deductible as they are made, and earnings on invested funds accumulate free of taxes. Pension benefits are subject to income tax when they are eventually paid out, but recipients are often in lower tax brackets by that time.

Taken together, preferences for retirement savings are one of the largest tax expenditures in the Federal Budget. The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center estimates that the immediate, direct revenue loss associated with contributions to IRAs and 401(k) plans will exceed $1 trillion over the decade beginning in 2011. That figure is the product of contributions multiplied by the applicable marginal tax rate. A more sophisticated estimate of the cost by the American Society of Pension Professionals & Actuaries suggests that the direct revenue loss, as calculated by the Tax Policy Center and others, overstates the true costs by as much as a third to a half, but even half a trillion dollars still makes a very large dent in the budget.

Unfortunately, tax preferences do little to increase retirement saving. Three factors undermine their effectiveness.

- As noted by William G. Gale of the Tax Policy Center, about three-quarters of taxpayers are subject to income tax rates of 15 percent or less. As a result, the very households who are most likely to have inadequate savings at the time of retirement gain little or nothing from the deductibility of retirement saving.

- Taxpayers in higher brackets have a larger incentive to contribute to 401(k) and similar plans. However, studies cited by Gale have found that the contributions of those higher-income households are much more likely to represent a reallocation into tax-preferred plans of funds they would have saved in any event.

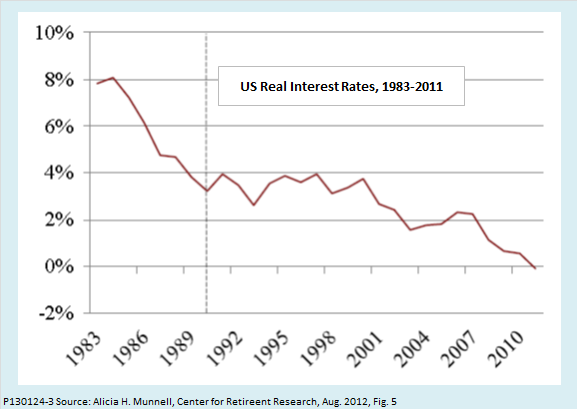

- As inflation has slowed, the benefit of tax-deferral of earnings on retirement plan contributions has decreased. For example, suppose the nominal interest rate is 8 percent and the inflation rate is 6 percent. For a household subject to a 25 percent income tax rate, the after-tax nominal interest rate would be 6 percent, just equal to inflation. That would make the after-tax real interest rate zero, compared with a tax-free nominal rate of 8 percent and a tax-free real rate of 2 percent. If the inflation rate falls to 2 percent and the nominal interest rate to 4 percent, the after- tax nominal rate is 3 percent, for an after-tax real rate of 1 percent. Meanwhile the tax-free real interest rate would remain at 2 percent. These are only illustrative numbers, but whatever the specifics, if we assume the before-tax real interest rate remains unchanged, slowing inflation reduces the relative attractiveness of tax-sheltered retirement plans.

In short, the present policy of encouraging private retirement savings by sheltering them from taxes is expensive but ineffective.

Two better ways to encourage retirement savings

There should be better ways to encourage retirement savings, and there are.

One idea, discussed by Thomas Gale in the paper cited above, would be to replace the current tax deductibility of contributions with a flat-rate credit. He describes the proposal as follows:

"First, unlike the current system, workers’ and firms’ contributions to employer-based 401(k) accounts would no longer be excluded from income subject to taxation, contributions to IRAs would no longer be tax-deductible, and any employer contributions to a 401(k) plan would be treated as taxable income to the employee (just as current wages are). Second, all qualified employer and employee contributions would be eligible for a flat-rate refundable tax credit, given to the employee. Third, the credit would be deposited directly into the retirement saving account, as opposed to the current deduction, which simply results in a lower tax payment than otherwise. . . . Contribution limits would not change. Earnings in 401(k) plans and IRAs would continue to accrue tax-free, and withdrawals from the accounts would continue to be taxed as income."

Gale proposes a 30 percent rate for the tax credit. A 30 percent credit would give the same incentive as a tax deduction for someone in a 23 percent tax bracket. For such a person, the after-tax cost of adding $100 to a retirement account would, under either the credit or the deduction plan, be $77. The tax credit would give a greater incentive than a deduction to people in tax brackets below 23 percent. That is just what we want, since those are the people now most likely to have inadequate savings when they reach retirement. For people in tax brackets above 23 percent, the incentive from the tax credit would be less than from a deduction. That is fine, because their contributions to tax-favored retirement accounts are more likely to be reallocations of existing saving than new saving.

According to Gale’s calculations, a 30 percent tax credit would be revenue-neutral compared to the current system of deductions. A credit at a lower rate would still provide some incentive to increased saving by lower-bracket households while increasing budget revenues compared to existing policy.

Alternatively, a second way to make it easier to save for retirement would be to reduce the risk and raise the return on funds invested in 401(k) and similar plans. A brief from the Center for Retirement Research cited in the preceding post lists falling real interest rates as one of the important barriers to successful retirement saving. The brief uses the chart reproduced below to illustrate the problem. The nominal interest rate on which it is based is that on bonds held in Social Security trust funds. Inflation is measured by the rate of change of the CPI for years up to 1991 and by 10-year inflation forecasts for later years. The real interest rate shown is the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate.

How could the government reduce the risk and increase the return on retirement savings? One way would be for the Treasury to issue a special series of retirement securities—call them R-bonds, for short. The R-bonds would have the following properties:

- They would be nonmarketable.

- Like all Treasury bonds, they would be free of default risk.

- Like Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), their principal value would be adjusted to reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index.

- Unlike TIPS, R-bonds would pay a guaranteed real interest rate (that is, an interest rate in excess of inflation) of, say, 2 or 3 percent.

- R-bonds could be held only in retirement accounts, with a limit on the maximum amount per individual.

Either a tax credit or R-bonds could increase the number of people who succeed in accumulating adequate retirement savings, but they would do so in different ways. A tax credit would work by increasing contributions to retirement accounts, but the accounts would remain risky. Depending on the market risks, default risks, and inflation risks to which a person’s retirement portfolio is exposed, the accumulated value at retirement age can turn out to be inadequate despite a lifetime of diligent saving. By reducing those risks, R-bonds, could increase the number of retirees who achieved minimally adequate savings even if they did not increase total saving.

Of course, if R-bonds ended up paying a higher rate of interest than ordinary Treasury bonds (as would likely be the case), they would increase the government’s interest expense. The increase could be offset by eliminating tax deductions for retirement contributions and taxing interest on retirement accounts. By adjusting the guaranteed real interest rate and the maximum amount of bonds per person, R-bonds, like tax credits, could be introduced in a way that was either revenue neutral or revenue enhancing.

Like tax credits, an R-bond program could be designed to increase retirement saving incentives for lower-income households while reducing the incentive of higher-income households to divert existing saving into tax-privileged accounts. The incentives and budget impacts could be fine-tuned further by using tax credits and R-bonds in combination.

Toward a secure, equitable, and affordable retirement policy

The bottom line is that the U.S. retirement system, as it exists, is neither secure nor equitable even as the stress it places on the federal budget increases. We can do better, and we should.

We should do better because there is an important public purpose in protecting citizens against unavoidable and privately uninsurable risks that can thwart the best-laid plans for retirement savings—the risk of losses or low returns, the risk of inflation, and the risk of longevity.

We can do better than the current combination of Social Security and private tax-sheltered savings plans. Social Security can be allowed to evolve toward a pure social safety net that provides poverty-level retirement protection for the neediest. Mechanisms such as tax credits directly deposited to retirement accounts or R-bonds with a guaranteed real return could substantially improve saving incentives, compared with the present system of tax deductions, without increasing the burden on the budget, or even decreasing it.

With a little imagination and the political will to act on it, we could end up with a retirement policy that is genuinely secure, equitable, and affordable.

Original post