In a post earlier this week, I explained why a majority of economists fear deflation. They argue that deflation disrupts the operation of financial markets and labor markets in a way that risks touching off a downward spiral. At the same time, they say, deflation weakens the power of monetary policy to reverse the downward slide. Even radical measures like quantitative easing have limited power. For that reason, the standard advice is to prevent deflation before it gets started. In the conventional view, that can best be done by maintaining a moderate but positive rate of inflation of 2 percent or so—enough to provide a cushion against unexpected economic shocks.

Not all economists are aboard the anti-deflation bandwagon, however. Some argue that deflation is actually a good thing, while others make the more nuanced argument that deflation can be either benign or malign according to circumstances. Let’s take a look at some of their arguments to see which make sense and which do not.

Three weak arguments in support of deflation

Before turning to the serious reasons why deflation might not always bad, let’s begin with three pro-deflation arguments that seem to me to be weak.

The benefits of low interest rates. Writing in Forbes, John Matonis tells us, “Contrary to the central banking and political class’s insistence that deflation must be prevented at all costs, an economy with a monetary unit that increases in value over time provides significant economic benefits such as near zero interest rates.”

To understand what is wrong with this argument, we need to distinguish between nominal and real interest rates. As we saw in the preceding post, nominal interest rates are those stated in terms of dollars of interest per year per dollar of the amount borrowed—the way interest rates are expressed on loan contracts and ads in the window of your local bank. The real interest rate, on the other hand, is the nominal interest rate minus the rate of inflation. The real interest rate represents the true burden on the borrower and the true return to the lender. If there is no inflation, a nominal interest rate of 5 percent means that a person who borrows $100 for a year at 5 percent will have to put up $105 at the end of the year to repay the loan, a sum that has a purchasing power 5 percent greater than that of the original $100 borrowed at the beginning of the year. On the other hand, if the loan terms are the same but there is 4 percent inflation over the course of the year, the $105 surrendered by the borrower has a purchasing power equivalent only about 1 percent higher than the $100 borrowed had at the beginning of the year. The real interest rate is just 1 percent.

The problem with Matonis’ contention that deflation brings low interest rates is that it applies only to nominal rates. In times of deflation, nominal interest rates go down, but when they get to zero, they hit their lower bound. We cannot have negative nominal interest rates—at least not for ordinary borrowing and lending between private parties. Once nominal interest rates hit the zero bound, then, any increase in the rate of deflation causes the real interest rate to increase. If the nominal rate is zero and we subtract a rate of inflation of -2 percent (that is, if prices are falling at 2 percent per year), then we get 0 – (-2) = +2 percent for the real rate. If the rate of deflation accelerates to 5 percent, then we get 0 – (-5) = +5 percent for the real rate, and so on.

In short, the faster the rate of deflation, the higher the real interest rate. If you want to ease the burden of borrowing in order to encourage people to buy cars and build houses, you need low real interest rates, so should strongly oppose any but the mildest forms of deflation.

Lower prices increase demand. On the web site of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Doug French writes, “Lower prices increase demand; they do not reduce or delay it. That’s why more and more people own flat-screen TVs, cellular telephones, and laptop computers: the prices of these goods have fallen, and people with lower incomes can afford them.”

The problem here is that the examples of flat-screen TVs and similar items pertain to decreases in relative prices. No one disputes that when the price of one good falls relative to others, demand for that good tends to increase. However, a decrease in relative prices is not deflation. Deflation means a decrease in the average price level of all goods and services. When the average price level falls, the sales revenues of producers also fall, which in turn, squeezes their profits and puts downward pressure on nominal wages. In short, because general deflation tends to cut both the average level of prices and average incomes, it does nothing to increase anyone’s purchasing power, whether they be rich or poor.

Deflation encourages saving. In an interview with Louis James, editor of the International Speculator, Doug Casey says, “Deflation can be a very good thing, because when dollars are worth more over time, it encourages people to save—and one of our big problems is that nobody’s saving.”

This is the exact opposite of French’s argument that deflation makes people spend more and save less. Both arguments can’t be true, and if French is wrong, then Casey could be right. In fact, he is right, at least in part. Rapid deflation does tend to push up real interest rates, and by itself, that does give people an incentive to save more. He is also right that in the long run, economies where people save and invest more will tend to grow more rapidly than ones where saving and investment are low.

The problem here is one of timing. An economic slump that is deep enough to produce rapid deflation is exactly the wrong time for added saving. As we saw in the preceding post, during a deflationary slump, borrowers are struggling to pay off expensive loans that they took out earlier when nominal interest rates were high. Banks are reluctant to make loans because they fear defaults and falling values of collateral. To get out of a severe recession like that, the economy needs more spending, not more saving.

Bad deflation and good deflation

Not all pro-deflation arguments rest on such weak foundations. A more credible argument holds that deflation may be bad, but it is not always bad.

Chris Farrell, a contributing editor at BloombergBusinessweek, puts it this way:

How fearful should we be of deflation? It depends on why prices are falling. Bad deflation stems from a “demand shock” in a highly indebted economy, say, a housing market implosion or collapsed banking system (the story of the Great Depression and Great Recession). . .

Deflation isn’t always bad, however. Sometimes, mild deflation can signal a vigorous, creative, healthy economy. Good deflation stems from a positive supply shock, e.g., a string of major innovations that combine to push down costs and prices while opening up new markets and opportunities.

In a more analytical paper, economist George Selgin says much the same thing:

The truth, however, is that deflation need not be a recipe for depression. On the contrary, a little deflation can be a good thing, provided that it is the right kind of deflation.

Since the disastrous 1930s, economists and central bankers seem to have lost sight of the fact that there are two kinds of deflation—one malign, the other benign. Malign deflation, the kind that accompanied the Great Depression, is a consequence of shrunken spending, corporate earnings, and payrolls. . . Strictly speaking, even in this case, it is not so much deflation itself that is harmful as its underlying cause, an inadequate money stock. In response, firms are forced to curtail production and to lay off workers. Prices fall, not because goods and services are plentiful, but because money is scarce.

Benign deflation is something else altogether. It is a result of improvements in productivity, that is, occasions when changes in technology or in management techniques allow greater real quantities of finished goods and services to be produced from a given quantity of land, labor, and capital.

A simple equation will help to understand the difference between good and bad deflation. Let P stand for the price level, Y stand for real GDP, and Q stand for nominal GDP. By definition, Q = P X Y. Malign deflation is driven by a collapse in nominal GDP, whether attributable to a decrease in the money stock (as Selgin suggests) or some other cause. As Q falls, both P and Y fall along with it. In contrast, benign deflation occurs when rising productivity causes Y to grow strongly, while monetary and fiscal policy hold Q unchanged, or allow it to grow a little, but not as fast as Y. By simple arithmetic, P must then fall, producing moderate deflation.

For three reasons, the benign, supply-side variant of deflation does not produce the downward spiral described in the first part of this series:

- Strong investment demand keeps real interest rates high enough to prevent nominal rates from hitting the zero bound despite a moderately negative rate of inflation. For example, we might have a 3 percent real interest rate and a -1 percent annual change in the price level, allowing a nominal interest rate of +2 percent.

- Strong demand for housing, factories, industrial equipment and other real assets supports the value of the collateral that backs bank loans. Even when occasional defaults occur, lenders are able to sell their collateral for enough to cover the outstanding balance of the loan.

- Rising productivity and full employment ensure that real wages are rising. Even if deflation holds the growth of nominal wages below that of real wages, it can still be positive. For example, real wages might grow by 4 percent per year while nominal wages grow by 3 percent. With paychecks growing and workers’ standard of living growing even faster, there is little cause for widespread labor unrest.

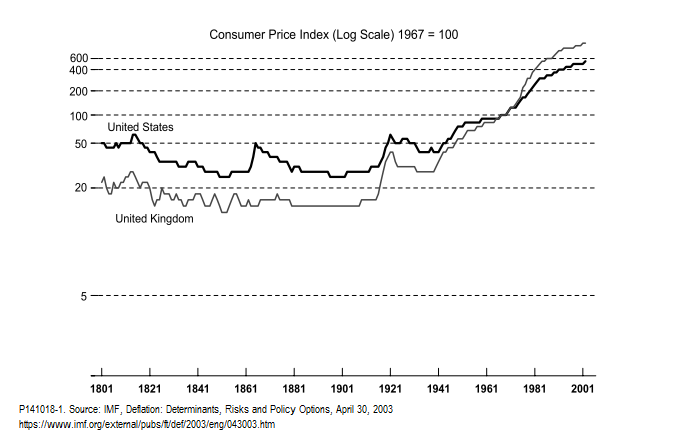

Can benign deflation happen in the real world? Yes. As the following chart from a 2003 IMF paper shows, the average trend of prices was downward in both the US and the UK throughout most of the nineteenth century, and more briefly, in the 1920s. These were, on the whole, periods of healthy economic growth, despite interruptions by periodic recessions in the nineteenth century.

Unfortunately, it has been almost 100 years now since any major economy has experienced a lengthy episode of benign, productivity-driven deflation. The best known deflation of recent years is that which has afflicted Japan on and off since the 1990s. It has been of the malign variety, accompanied by stagnation of real output and rising unemployment. The deflation now threatening the eurozone is clearly more like Japan’s than like the benign inflation of the 1920s.

Is it really all that hard to reverse deflation?

Finally, some economists argue that we need to have no fear of deflation, not because it is good, but because it should be easy to reverse and even easier to avoid. The trick, they say, is to provide monetary and fiscal stimulus in a sufficiently vigorous and coordinated way. This argument has been made by modern monetary theorists like William K. Black and also by more orthodox economists like Willem H. Buiter, chief economist at Citigroup.

According to this view, monetary policy alone, even in the form of quantitative easing (QE), cannot cure severe deflation. Although QE floods the banking system with new reserves, growth of reserves does not by itself guarantee more lending and spending. That is especially true in a slump, when potential borrowers are already struggling to work off excessive debt and lenders are afraid of defaults and falling prices for collateral. Fiscal stimulus, whether in the form of additional government purchases, tax cuts, or transfer payments, cannot do the job alone either. According to the conventional view, without support from monetary stimulus, fiscal stimulus would drive up interest rates, which in turn would crowd out private spending and make the stimulus less effective.

The right course, then, would be to apply expansionary fiscal and monetary policy together, in massive doses if necessary. Buiter calls large-scale tax cuts or transfer payments financed by the monetary expansion “the combination that always succeeds.”

How exactly could we implement such a policy? Milton Friedman famously proposed that the Fed could print tons of fresh $100 bills and drop them over city streets and shopping malls from a helicopter. People would treat the $100 bills as newfound wealth and would spend at least a substantial part of the windfall. Paper currency, although technically a liability of the federal government, bears no interest, so it would not push up interest rates and crowd out private borrowing. Because paper currency has no expiration date, it does not require tax increases or cuts in other spending to service the debt. A helicopter drop would be a foolproof way to stimulate aggregate demand.

In practice, there would be no need for actual helicopters. The Treasury could accomplish exactly the same thing by mailing tax rebate checks to every household. For internal bookkeeping purposes, it would cover the checks by selling an equivalent quantity of newly issued Treasury bonds to the Fed, which, in turn, would credit that amount to the account it keeps open for use by the Treasury. Just like a literal helicopter drop, this operation would give consumers a windfall increase in wealth without increasing the net amount of redeemable, interest-bearing government debt in the hands of the public. Instead of transfer payments, an increase in government purchases of goods and services, financed in the same way, would have much the same effect.

However, although the economic logic of a helicopter drop is strong, political constraints make such a policy hard to implement. One such constraint is the belief that a prudent government should confront hard times in the same way that a household does, by cutting expenditures and paying off debt. This view, often derisively called “austerianism,” is particularly strong among politicians and the general public in Germany and the United States.

Japan is the country that has done the most to use coordinated fiscal and monetary expansion to break out of deflation. Shinzo Abe, prime minister since December 2012, has backed an expansionary program, popularly known as “Abenomics,” that consists of three components (three “arrows”, he calls them). The first is monetary policy that targets a 2 percent minimum rate of inflation (rather than treating 2 percent inflation as an upper limit, as in the EU). The second arrow is expansionary fiscal policy and the third is a package of pro-growth structural reforms.

To date, however, only the monetary component has come fully into force. An increase in consumption taxes earlier this year seriously undercut the fiscal component while structural reforms have been slow to get off the ground. Although inflation has been above the 2 percent mark since April, growth of real GDP fell below zero in the second quarter, breaking a run of three quarters of strong growth. The ultimate success of Abenomics remains uncertain.

The bottom line

We have now reviewed five reasons not to fear deflation. None of their supporting arguments can be accepted without reservation and some not at all.

The first three reasons are the claims that deflation benefits the economy through low interest rates, increased spending, and increased saving. Each of these arguments appears to rest on faulty economic reasoning.

The fourth reason is that deflation can take both good and bad forms. This proposition appears to be conceptually sound. It is further supported by historical episodes in the US and UK when economies experienced sustained economic growth combined with a falling price level. The only problem is that the deflation that Japan has experienced on and off since the 1990s and that which faces the eurozone today are clearly of the malign variety, driven by a collapse of demand rather than a productivity boom. At least in the short run, the benign deflation scenario looks more like a theoretical and historical curiosity than a serious pathway to prosperity for Europe.

The final reason not to fear deflation is that even if it is harmful, it can easily be reversed through a sufficiently strong and properly coordinated program of fiscal and monetary stimulus. The necessary stimulus could come in the form of a hypothetical “helicopter drop,” or more concretely in the form of something like Abenomics. The reservation here is that although the economic reasoning is sound, there is strong political resistance in many countries to implementing any such policy.

The bottom line, then, is that Europeans are right to fear deflation. Countries such as Greece, Spain, and Italy where prices have been falling are experiencing high unemployment, declining living standards, and social unrest. Others that are slipping toward deflation, like France and Belgium, fear the same outcome. France and Italy are currently making a last-ditch effort to form an anti-austerity coalition within the eurozone. They appear to have the support of Mario Draghi at the European Central Bank. However, they are meeting stubborn opposition from German politicians who remain determined to balance their own budget despite a slowing economy and to enforce strict budget rules for the rest of the currency area. The eurozone economy, then, appears poised between outright deflation and mere stagnation, with an early return to prosperity no more than a slim hope.