Last week’s convergence report from the European Commission gave Latvia the green light to become the eighteenth member of the eurozone as of next January. “The eurozone is again a club with a queue–not at the exit but at the entrance,” crowed Herman Van Rompuy, president of the European Council. “Joining the eurozone will foster Latvia’s economic growth, for sure,” Latvian Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis said in Riga. Yet Latvians on the street are less certain. Public opinion polls show that only about 35 percent of respondents favor the switch, and opposition parties that oppose the euro have done well in recent local elections.

Who is right? Is it really a good idea for Latvia to sign on for membership in Europe’s troubled currency union? Let’s look at some of the factors that would make the answer “yes” or “no.”

Criteria for an optimal currency area

We can begin by setting Latvia and the euro to one side to look at the broader question of which countries or regions might benefit from common currencies. Imagine that we sit down with a blank outline map of the world and try to fill it in so that countries and regions that are better off sharing currencies are assigned the same color. We ask questions like these: Should Maryland and Virginia both use the dollar? If yes, color them both green. Should Russia and Ukraine both use the ruble? If yes, color them both red, and so on. When our map is finished, the regions with the same color—whether they are sovereign nations, groups of nations, or regions that overlap national borders—are what economists call optimal currency areas.

The theory of optimal currency areas can be traced back to a 1961 paper of that name by Robert Mundell. Mundell emphasized that making the case for a common currency is a matter of balancing advantages against disadvantages. Economically, the advantages are reductions in the costs of trade—eliminating the need to buy and sell currencies, to hedge exchange rate risks with futures or swaps, and the like. The economic disadvantages stem from the fact that a country with a shared currency cannot respond independently to external shocks by using monetary instruments like changes in interest rates or exchange rates. Mundell also recognized a role for political factors in the choice of currency arrangements. Interestingly, at that time, he saw the question of currency areas as purely academic, seeing it as “hardly within the realm of political feasibility that national currencies would ever be abandoned in favor of any other arrangement.”

Mundell’s paper inspired a search for more specific criteria that would weigh for or against membership in a currency area. The factors emphasized by early contributors to the literature include:

- The extent of trade between members of the currency area. Obviously, countries that don’t trade much with each other, say Iceland and Chad, would have little to gain from sharing a currency. By comparison, the need to exchange currencies every time a Virginian bought something from a Marylander would be a burden best avoided.

- Flexibility of labor markets. Because countries with shared currencies cannot independently use monetary policy to respond to inflationary or deflationary shocks, it is important that labor markets be able to absorb those shocks through increases or decreases in wages, hiring or laying off of workers by firms and industries, and free geographic movement of labor within the currency area.

- Symmetry of exposure to external shocks. Consider an example. If a country is an oil exporter, an increase in global oil prices will be expansionary, and its central bank would want to respond with measures to prevent overheating of the economy. If the country is an oil importer, the central bank would try to soften the contractionary impact of an oil price increase. The shared central bank of a currency area in which all members were oil importers or oil exporters could equally well act in an appropriate way. However, the central bank of a currency area that included some oil importers and some exporters would face a dilemma; any actions it took to help some members would risk harming others.

Viewed in terms of these criteria for optimal currency areas, Latvia looks like a rather good candidate for membership in the eurozone. It trades mostly with other euro members, so it stands to gain significantly from any reduction in transaction costs. Its labor markets are relatively flexible—much more so than the notoriously rigid labor markets of many euro members, including France, Spain, and Italy. Its exposure to external shocks is reasonably symmetrical with those of Germany and the Nordic countries that are its main trading partners. Its largest trading partner outside the EU is Russia, and in that case, the floating exchange rate between the euro and the ruble can help adjustment to asymmetrical shocks and low labor mobility.

The EU convergence criteria

The European Union has laid down its own set of convergence criteria for letting new members into the euro. These have little to do with the classic criteria for an optimal currency area, and some of them have been criticized for making little sense. Nevertheless, Latvia has successfully met all of them.

- Legal convergence. New members must have appropriate legal frameworks governing monetary and fiscal policy. This point is relatively uncontroversial, and Latvia has tweaked its laws as necessary to meet it.

- Convergence of inflation rates. To join the euro, a new member must have an inflation rate that is no more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the inflation rates of the three “best performing” members of the EU, that is, those with the lowest inflation rates. Latvia safely meets that criterion, with inflation of 1.3 percent compared to a benchmark of 2.7 percent. Still, it is worth pointing out that economists see the criterion itself as very odd. First, it makes no allowance for the possibility that some of the “best performing” EU countries could be suffering from pathological deflation or could have low inflation only because they are in deep slumps. Second, some of the benchmark countries may not even be members of the euro, raising the paradoxical possibility that a candidate might have lower inflation than any current euro member, yet still be excluded. Third, the candidate is allowed to serve as one of its own benchmarks. As if to confirm these oddities, the inflation benchmark states for Latvia are Ireland (struggling to recover from a deep slump), Sweden (not a euro member), and Latvia itself.

- Exchange rate stability. Prospective euro members are required to prove they can maintain a stable exchange rate relative to the euro before they enter. Specifically, they must keep exchange rate fluctuations within a band of no more than plus or minus 15 percent around a central target value. Latvia has no problem with this one; it has kept its currency, the lats, within a band of plus or minus 1 percent around a peg of .7 lats per euro since it joined the EU in 2004.

- Long-term interest rates. The final criterion is that a candidate country have long-term interest rates that are no more than two percentage points higher than those of the three best-performing EU members. This criterion could be criticized as redundant, since a country that maintains low inflation and a responsible fiscal policy is unlikely to have excessively high long-term interest rates. In any event, Latvia meets this standard easily at present.

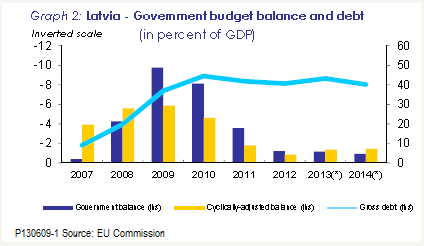

- Public finance.Probably the most important criterion is that a candidate for entry into the euro must show it can keep its public finances in order. The standing rule is that a country’s budget deficit should be less than 3 percent of GDP and its debt less than 60 percent of GDP. As the following chart shows, Latvia is currently well within these limits. The limits themselves are open to criticism, however. In particular, as EU authorities have come to recognize over time, it would make more sense to focus on a country’s cyclically adjusted budget balance rather than the current balance, which can be distorted by the state of the business cycle. Fortunately for Latvia, both its current and structural balances are in good shape at present.

Challenges that lie ahead

Although Latvia appears to meet both the classic criteria for membership in an optimal currency area and the EU’s formal convergence criteria, those do not tell the whole story. Membership in the eurozone will not always be easy, in part because of circumstances particular to Latvia, and in part because the eurozone itself is not in all respects an optimal currency area.

First, it is not likely that inflation in Latvia will stay as low as it is now. When Latvia joined the EU in 2004, it was the poorest member, with per capita income just 33 percent of the EU average. By 2011 that had risen to 53 percent, and the convergence of incomes will presumably continue. However, there is a strong tendency for a relatively poor, fast-growing country that has a fixed exchange rate to experience faster inflation than do its trading partners. As a euro member, Latvia will not be able to use monetary policy or exchange rates to manage its inflation rate.

Second, faster real growth and faster inflation will make management of fiscal policy more difficult. During the boom of 2004 to 2007, instead of letting rising tax revenues push the budget into surplus (as happened in neighboring Estonia), the Latvian government, yielding to populist pressures, raised government salaries and social benefits. The resulting overheating of the economy intensified the crash that followed the global economic crisis in 2008 and 2009. As a result, even more severe austerity measures were required than would otherwise have been necessary. Careful fiscal management will be needed to avoid a repetition of that scenario.

Third, Latvia faces a difficult demographic situation. Its total fertility rate has fallen sharply since the early 1990s, and now, at about 1.4 births per woman, is well below replacement. As a result, the country faces a steadily increasing number of retirees per worker. The rising burden of pensions and healthcare threatens to encourage emigration by young people, making the situation even worse. True, Latvia also attracts inward migration, including many professionals, and that should be encouraged, since the taxes they pay helps offset the drain of emigration. Still, it would be better if the EU as a whole tackled the problem by balancing its policy of free labor migration with a centralized pension scheme like the American Social Security system. However, any such move seems politically unrealistic for the foreseeable future.

Fourth, the eurozone as a whole faces serious unresolved problems with its banking system. Logically, a currency union should balance free capital flows among its members with a centralized system of bank supervision and resolution for insolvent financial institutions. Despite much talk, however, that is unlikely to happen soon in the eurozone, leaving it vulnerable to recurrent banking crises in member states. Fortunately, Latvia’s banking system is small relative to the size of its economy and is dominated by well-managed banks based in neighboring Nordic countries. Latvia does have a few banks of its own that specialize in offshore deposits from countries of the former Soviet Union, but the relatively small size and closer regulation of these institutions will, hopefully, prevent any repetition of the kind of crisis that has recently shaken Cyprus.

The bottom line

The bottom line is that the eurozone is not in all respects an optimal currency area. By joining it, Latvia signs on to share its problems as well as its benefits. Still, we should not exaggerate the drawbacks of membership. One reason is that Latvia has already lived with a fixed exchange rate ever since its independence in 1991. Arguably, a more flexible exchange rate regime would have moderated the extreme boom-bust cycle of 2004 to 2009, but that period is now behind it. With good management of fiscal policy, Latvia can hope that the next stages of its ongoing convergence with wealthier EU countries will go more smoothly.

Finally, we should keep in mind that the choice of joining the euro is as much a political decision as an economic one. Latvia likes to view itself as a bridge between Eastern and Western Europe. Financial ties, transportation links, and widespread fluency in the Russian language all create opportunities to profit from that position. Still, while Latvia cultivates good economic relations with former Soviet counties to the East, it will be prudent for it to maintain secure political anchors in the West. Government officials make it clear that they view the euro as one more such anchor, along with existing memberships in NATO and the EU. Finance minister Andris Vilks (as reported in the Financial Times) has said, “We are in a very fragile geopolitical location. We should be as deeply integrated as possible into European institutions.” Edgars Rinkevics, the foreign minister, adds, “My main message is that Latvia is joining the euro as a geopolitical choice.” Putting both economics and politics together, the choice seems like the right one.

Original post