Summary: Japan has remained in economic stagnation for so long we have come to consider that as normal. It’s not. Slow decay of a nation eventually ends in reform (as expected in Japan by experts for 2 decades) or regime change. Abenomics aroused excitement as the start of powerful reforms, as Japan’s last chance. The past few months’ data suggest that failure lies ahead. If so, after that will come exciting and unexpected events (but not necessarily beneficial or pleasant events). They will affect the world (especially if Japan walks a path on which America and Europe follow). Let’s review the evidence.

“GDP figures for July-September turned out not so encouraging.”

– Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, 17 November 2014 (source: Reuters)

”The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage …”

– Emperor Hirohito of Japan in his first radio broadcast, 15 August 1945

Contents

- Dark day for Abenomics

- Implications

- What’s the problem with Japan

- The bad news (lessons from history)

- For More Information

(1) Dark day for Abenomics

In the dark days before Abenomics, as Japan neared the quarter-century milestone for stagnation despite massive economic stimulus (running the government’s debt up to incredible levels), experts wrote that “Something is wrong with Japanese politics“, and about the necessity of “Restoring Political Stability“.

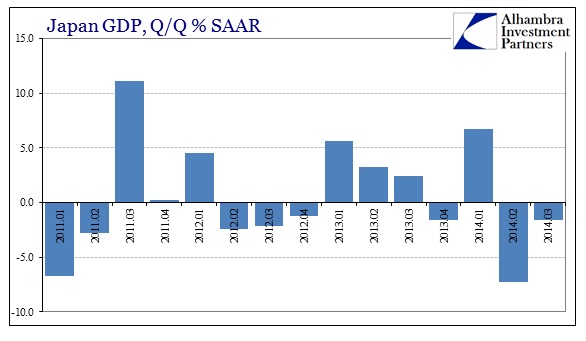

Abe has been prime minster since 26 December 2012. His political strength came from the desperation of his people after almost a quarter-century of the hopes of recovery he aroused, and his bold measures to revitalized Japan (“Abenomics”). Now that Japan enters a triple-dip recession, let’s turn from Wall Street’s happy outlook to ask about the effects should Abenomics fail? And it is failing, despite strong corporate profits and massive stock market gains, as described in this report by Alhambra Investment Partners: “The Inevitable End“.

Real GDP, from Alhambra Investment Partners, 17 November 2014

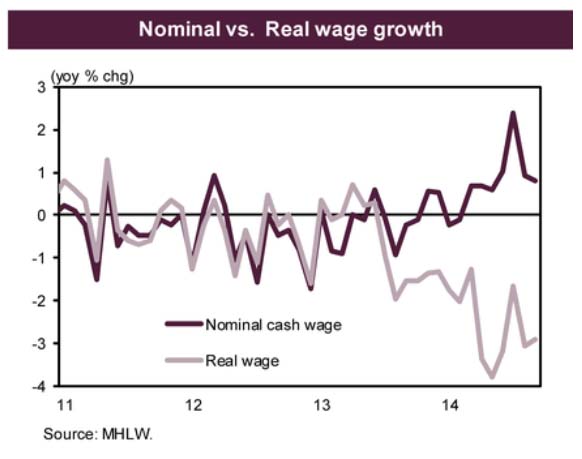

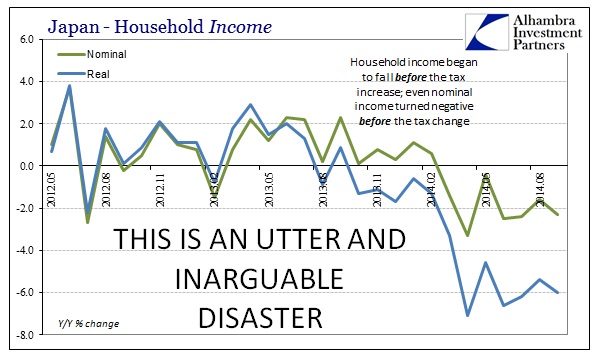

Perhaps even worse, Abenomics has lowered the value of the yen. While wonderful for corporate exporters and good for their workers, this has proven horrific for everybody else as the cost of imports rises faster than wages (and faster than fixed incomes, such as pensions) — without the promised economic acceleration. Another recession will further increase stress on people, as the yen drops even more — with even less offsetting job and wage growth.

.

.

From Alhambra Investment Partners, 11/11/2014

(2) Obvious Implications

The third of Abenomics “Three Arrows” is deep structural reform of Japan’s economy. He’s announced reforms, most recently in June. Most analysts consider these too small. They might also prove too late, announced after his political power had peaked. A recession might diminish the political power needed to push these (and necessary larger ones, later) through against the famously entrenched special interest groups that run Japan.

Abe’s expected to call for a snap election, before his support evaporates. Which it’s likely to do if the recession continues, as explained in this excerpt from a lecture by Professor J.A.A. Stockwin (Prof of Japanese Studies, Oxford), Paris for the Fondation France-Japon, 3 May 2011:

The most striking of these is the rapid turnover of prime ministers that has been occurring. Between 2006 and 2011 Koizumi, Abe, Fukuda, Asō, Hatoyama and now Kan have successively occupied the prime minister’s residence. That is 6 prime ministers in 5 years … since Koizumi stepped down in September 2006, not one of his successors has yet managed to stay in post for as much as a year. Over the same period there have been 3 British prime ministers, 2 French presidents, and 2 German Chancellors.

There are some other indicators of political instability as well. Prime ministers come to office with relatively high approval ratings, usually in the 50% to 60% range, but these rapidly fall, so that towards the end of their tenure public opinion polls showed an approval rating of 26 % for Abe, 19% for Fukuda, 13% for Asō, 17% for Hatoyama, and about 20% currently for Kan.

Another indication is that voting patterns, which used to be remarkably stable and predictable, have become exceedingly changeable and difficult to forecast. Huge blocs of voters seem to change their votes at each election, mainly against the government in power at the time. The LDP was elected in a landslide in the House of Representatives in 2005, the DPJ almost exactly reversed that position in its favour in 2009, and if elections were held today it seems quite possible that the position would be reversed once again. Since the 1990s those declaring no party allegiance to public opinion pollsters have been a majority of electors, and there is anecdotal evidence that many electors have a low opinion of politicians in general, while perceiving that prime ministers are endemically weak.

… In Japan as in other democratic countries, the electorate rewards governments when things are going well and punishes them when things are going badly. The mass media, with one eye on the electorate, are particularly tough on governments whose policies do not work out well, even when the failure of policies is brought about by difficult economic conditions rather than by lack of effort or perspicacity on the part of governments. Opposition parties also, quite naturally in terms of their aim of replacing the ruling party or parties in office, readily take advantage of a government’s difficulties to disrupt its performance.

This instability makes it difficult to build a consensus on new public policy, especially painful ones. The public’s low confidence in politicians and political institutions gives new governments little time to show results. That’s an ugly combination. Japan’s people hoped that Abenomics was the solution, a break with this past. Yet another disappoint might return Japan to years of impotent political instability.

(3) What’s the problem with Japan?

Before we look at deeper results from Abenomic’s possible failure, let’s consider the problem. Western experts explain that Japan has not sufficiently copied the West, and needs more neo-liberalism (the “third arrow”). However if the US and Europe are following Japan, that’s not the problem. Keiichi Tsunekawa (National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Japan) points instead to Japan’s political and social institutions, much as Karel van Wolferen did in his prophetic book The Enigma of Japanese Power (1989; essential reading for anyone seeking to understand events in Japan): “Political Economy of Stagnation and Instability in Contemporary Japan”. Abstract:

Different from dominant literature in the field, this paper does not regard the inadequate neoliberal reforms as the main source of economic stagnation and political instability of contemporary Japan. This paper argue s that the real problem Japan faces today is policy drift in which any policy, either more neo-liberal or more statist, does not last long enough for voters to judge which policy and supporting institutions are most appropriate for renewed and sustained growth of the economy. This policy drift is a reflection of the lack of a consistent ruling coalition, which in turn is the result of the specific mode of state formation and transformation in Japan.

In the specific political context in postwar Japan, the state was formed as a combination of the developmental and clientelist sub-states. Partially because they were so successful and entrenched and partially because organized labor failed to champion the welfare – state agenda, the developmental and clientelist sub-states have not been replaced but joined by the welfare and neoliberal sub – states as the economy matured. As a result, socio-political cleavages blurred and created a huge group of amorphous voters.

Rapid shifts of voters between parties by “amorphous” voters unable to commit to one political agenda? The causes differ, but this sounds like America, with our frequent “decisive” elections (most recently in 2008 and 2014, both sparking discussion of a broken major party).

(4) The bad news (lessons from history)

After a quarter century of economics stagnation, supported by multiple rounds of government stimulus, marked by repeated failed solutions, what might come next. The two readings above suggest the alienation of large fractions of society from Japan’s political system (imposed on them by the US after WW2). Nature abhors a vacuum. Something will replace this. Some group of leaders will replace the endless series of almost interchangeable grey bureaucrats who have run Japan into the ground. It’s not possible to reliably predict when, or who, or what they’ll be.

Regime change in Japan would be the second large milestone in the end of the post-WW2 geopolitical era (a transition begun on 9 November 1999 with the demolition of the Berlin Wall).

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

— Herbert Stein’s Law (US economist, 1916-1999)

“There are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen.”

– attributed to Lenin