The stock market is betting on a Goldilocks scenario. Jerome Powell doesn’t foresee a recession, instead, he forecasts a soft landing. Apollo is bettering the soft landing scenario with an optimistic “no-landing.” Regardless of which description you choose, all three are bets that a recession will not occur.

Assuming the markets, Apollo and Powell are right, stocks may have already bottomed with a new high not too far away. Accordingly, investors buying into a soft or no landing should ignore numerous recession warnings and load up on stocks.

However, suppose the soft landing crowd is wrong and recession warnings, such as the yield curve and most national and regional manufacturing surveys, prove prescient, as they reliably have. In that case, 2023 may be a rough year for the stockholders.

While a soft landing may be good for stocks, recessions and stock prices are not the best of bedmates. Therefore to better appreciate what a recession is and how we can better track the odds of a recession, we lean on the arbiter of recessions, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Recession Rule of Thumb

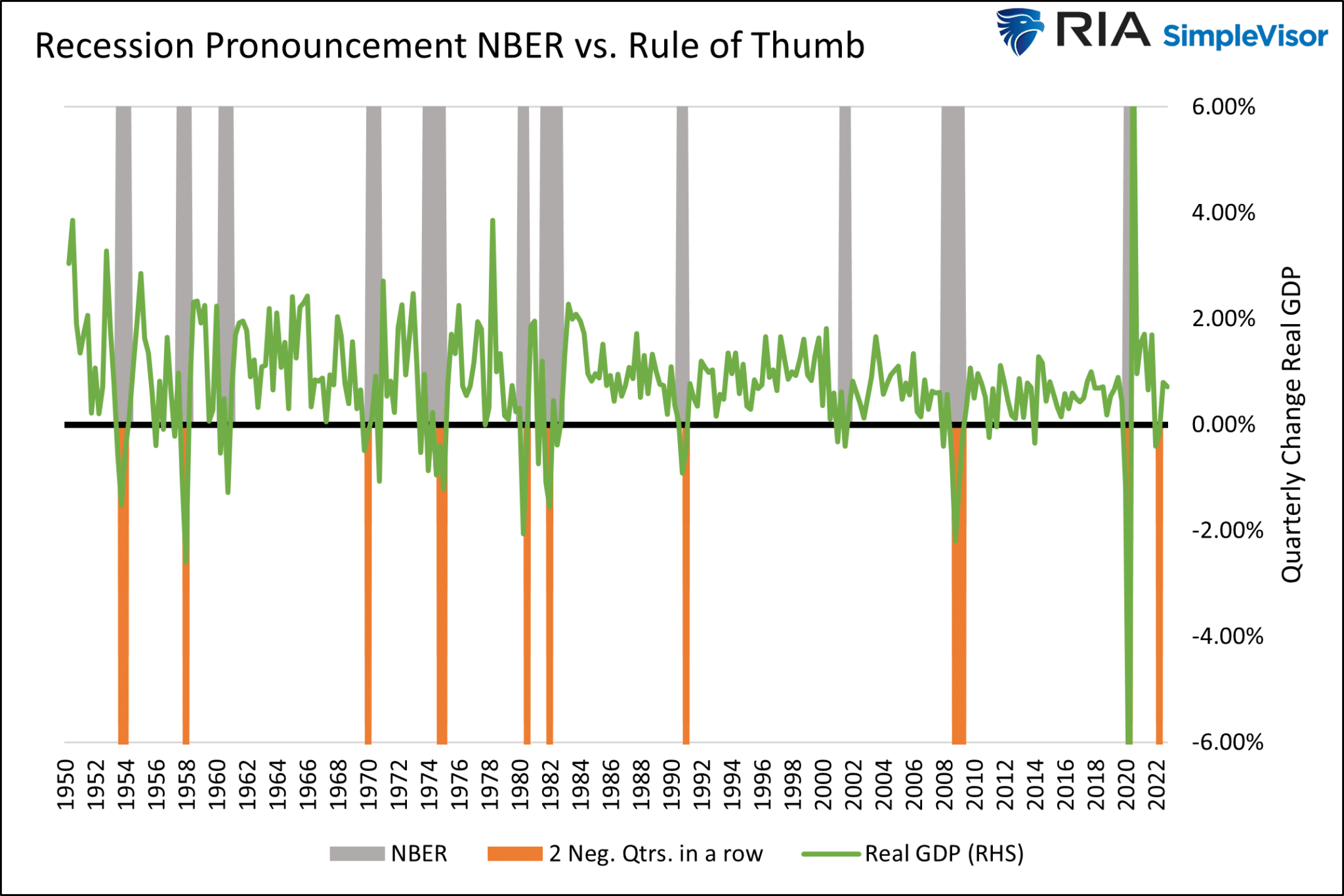

Before discussing the NBER, it is worth looking back a year. In 2021, real GDP declined in the first and second quarters. Quite a few economists and investors following a popular recession rule of thumb declared the economy was in a recession. The recession rule of thumb states that two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth constitute a recession. Investors shying away from stocks because of that rule of thumb may have missed an 18% gain in the year’s first six months.

The official determiner of recessions, the NBER, does not consider two consecutive quarters of negative growth a recession. We will discuss their approach shortly.

The graph below compares NBER declared recessions to the two consecutive negative quarters rule of thumb. As we see to the right, the rule of thumb-2022 recession was never an official NBER recession. Further, the rule of thumb didn’t see the recession in 2001 or 1961. In 1970, it was slightly early in calling a recession, and it was late in 2008, 1990, and a few other instances.

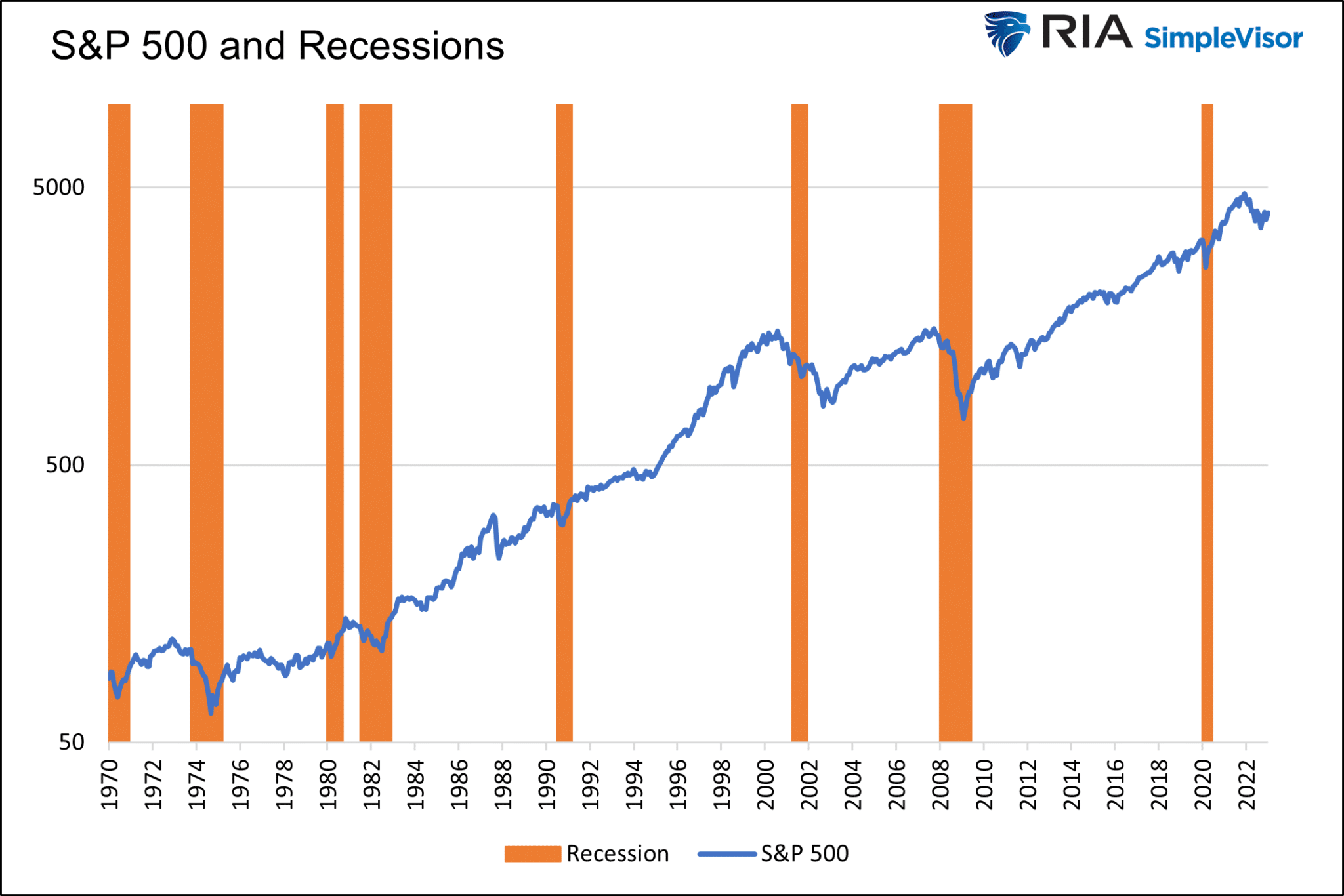

Getting a recession forecast right and early is essential. As shown below, stocks tend to decline three to six months before a recession starts. Being late on a recession call or failing to forecast a recession can prove costly.

NBER Cycle Dating

The NBER provides a succinct summary of how they determine whether the economy is in a recession. Per Business Cycle Dating, the NBER considers a recession a “significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.”

The definition is vague, given the massive amount of economic data they parse to assess the economy. However, there is a shortcut we can model to help predict when the NBER will make its recession call.

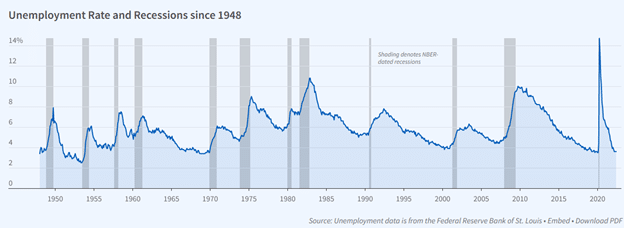

The first hint to finding this shortcut is the graph pasted at the top of the NBER’s aforementioned article.

The NBER chose to graph unemployment and place it just below the article’s headline. The clear intention is to show the strong correlation between higher unemployment rates and recessionary periods.

Employment and Wages Matter Most

The second hint is in the following paragraph:

The determination of the months of peaks and troughs is based on a range of monthly measures of aggregate real economic activity published by federal statistical agencies. These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production.

This paragraph provides a rundown of what they consider the most critical factors to determine the state of economic activity. Three of the six indicators are based on wages and employment. Another, real personal consumption expenditures, heavily depend on employment and wages.

Reading on, the NBER seemingly provides the secret formula as follows:

In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.

NBER Modelling

Armed with the two data points the NBER considers most valuable, we created an NBER recession model. The model helps us ascertain if we are or are not in a recession, but more importantly if the economy is trending toward one.

Before sharing our model, we review the two measures on which the NBER puts the most weight.

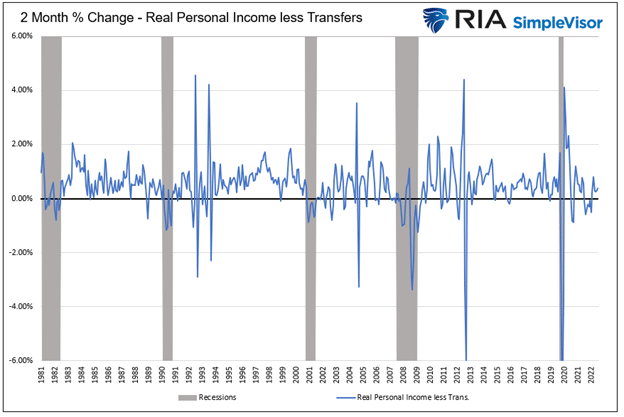

Real Personal Income Less Transfers is the total amount of personal income adjusted for inflation, less any income from government subsidies and benefits. Government transfers include Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid, unemployment assistance, special COVID benefits, and many other items.

As we show, real personal income less transfers tend to decline during recessions, but it has also dropped outside of recessions on multiple occasions. It is not a perfect indicator.

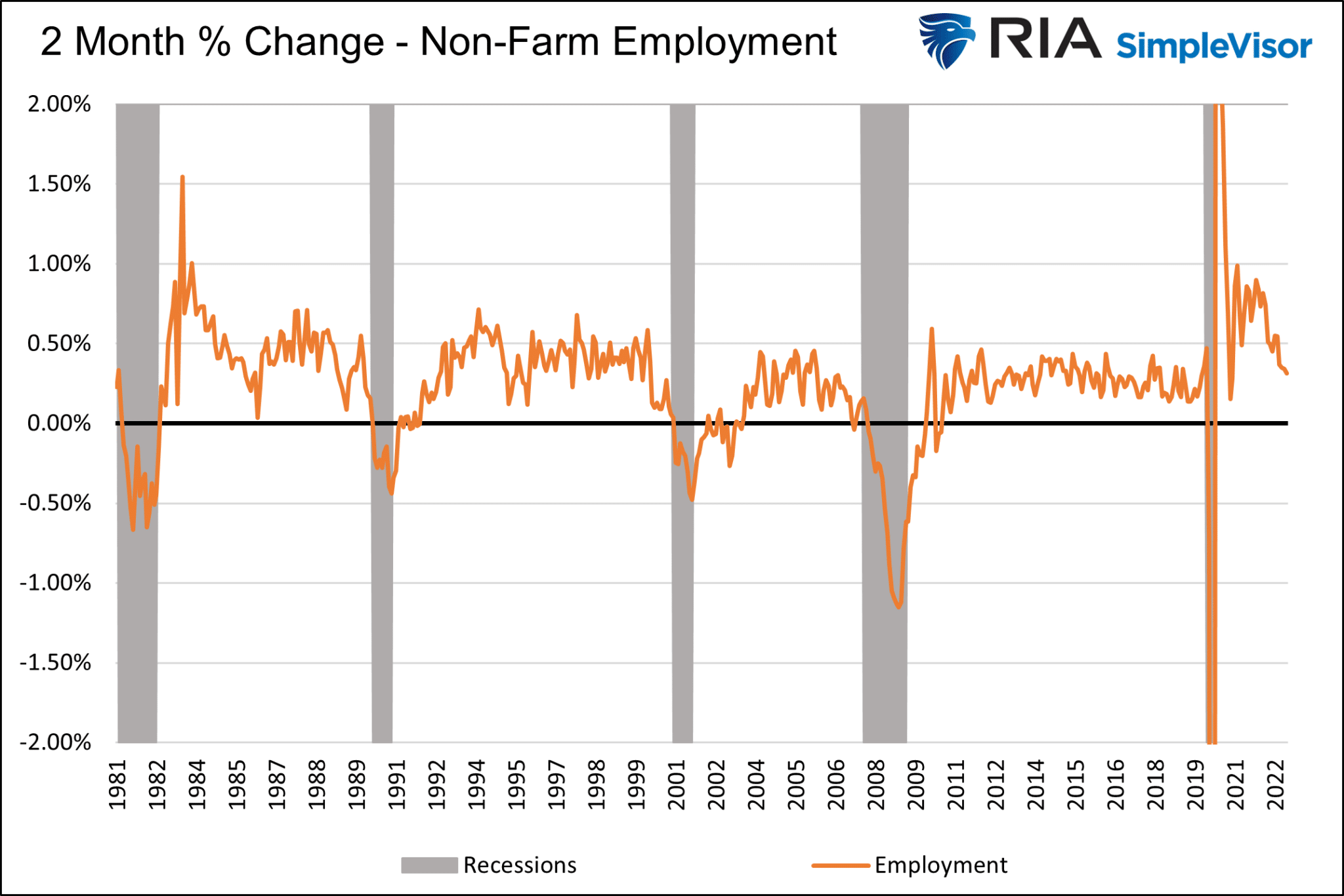

Nonfarm Payroll Employment measures the number of employees excluding farm workers and a few other job classifications. The graph below shows that negative employment growth for two quarters or more coincides with NBER recessions. A few negative readings did not correspond with recessions, but they all happened shortly after a recession.

With the two measures the NBER puts “the most weight on” we created a model that has proven to be accurate and relatively timely.

NBER Proxy Model

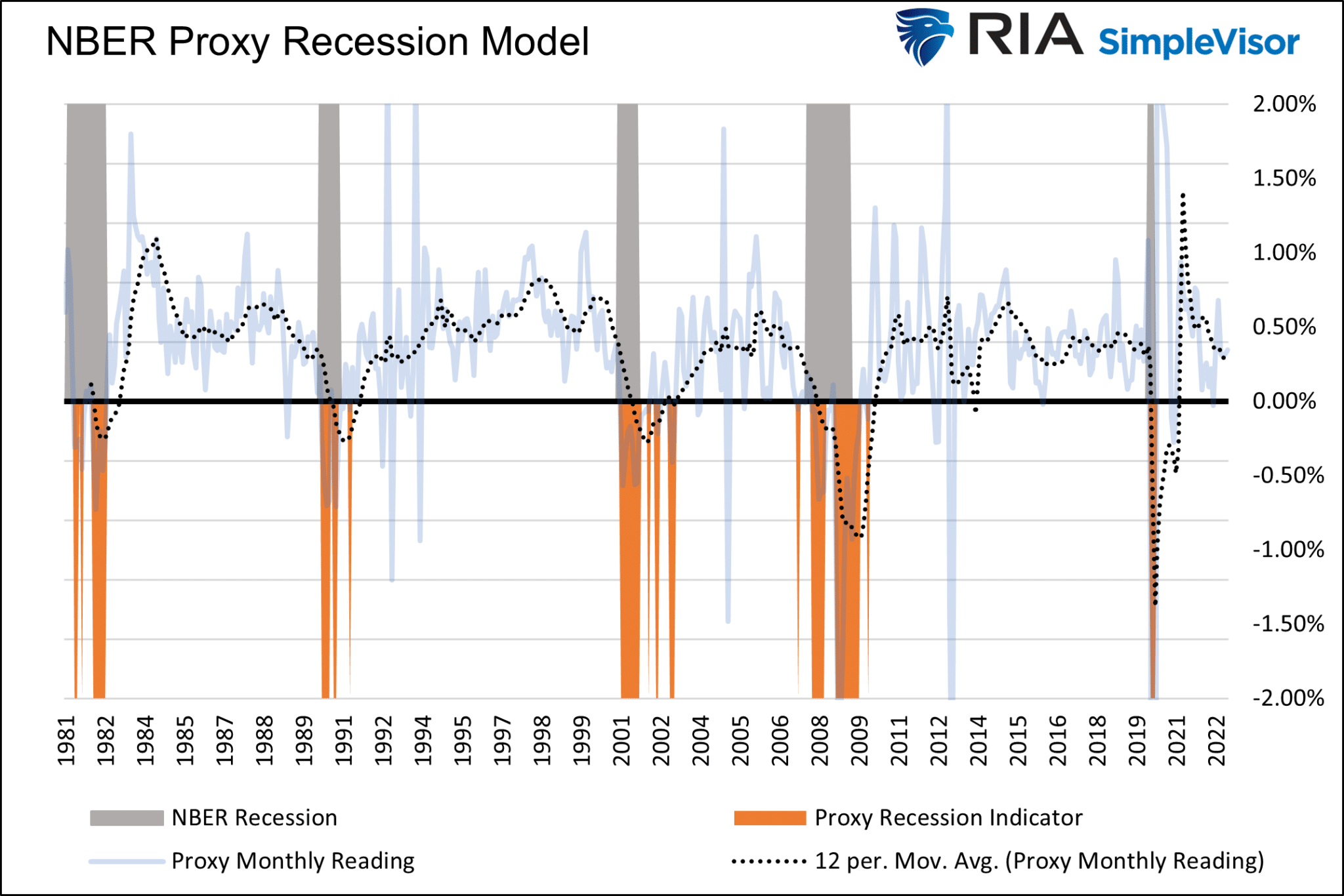

The graph below compares the proxy model recession indicator in orange to the NBER recessions. The indicator is often accurate within three months. Only once, in 2007, did it provide an early warning. However, it produces false signals during the recovery period following a recession.

The indicator is the light blue line. The dotted one-year moving average helps see the recent trend. As it shows, a recession is not imminent. The movement has generally been declining toward recession, but it resides at levels in line with economic expansion over the last decade.

Understanding the two pieces allows us to use this proxy model and, more importantly, follow employment, income, and inflation to provide potential early warnings that a recession may occur soon.

Staying Ahead of our Model

Now that we know two crucial recession indicators, we must ask how else we can stay ahead of a recession. The obvious answer is to understand when incomes and employment will decline.

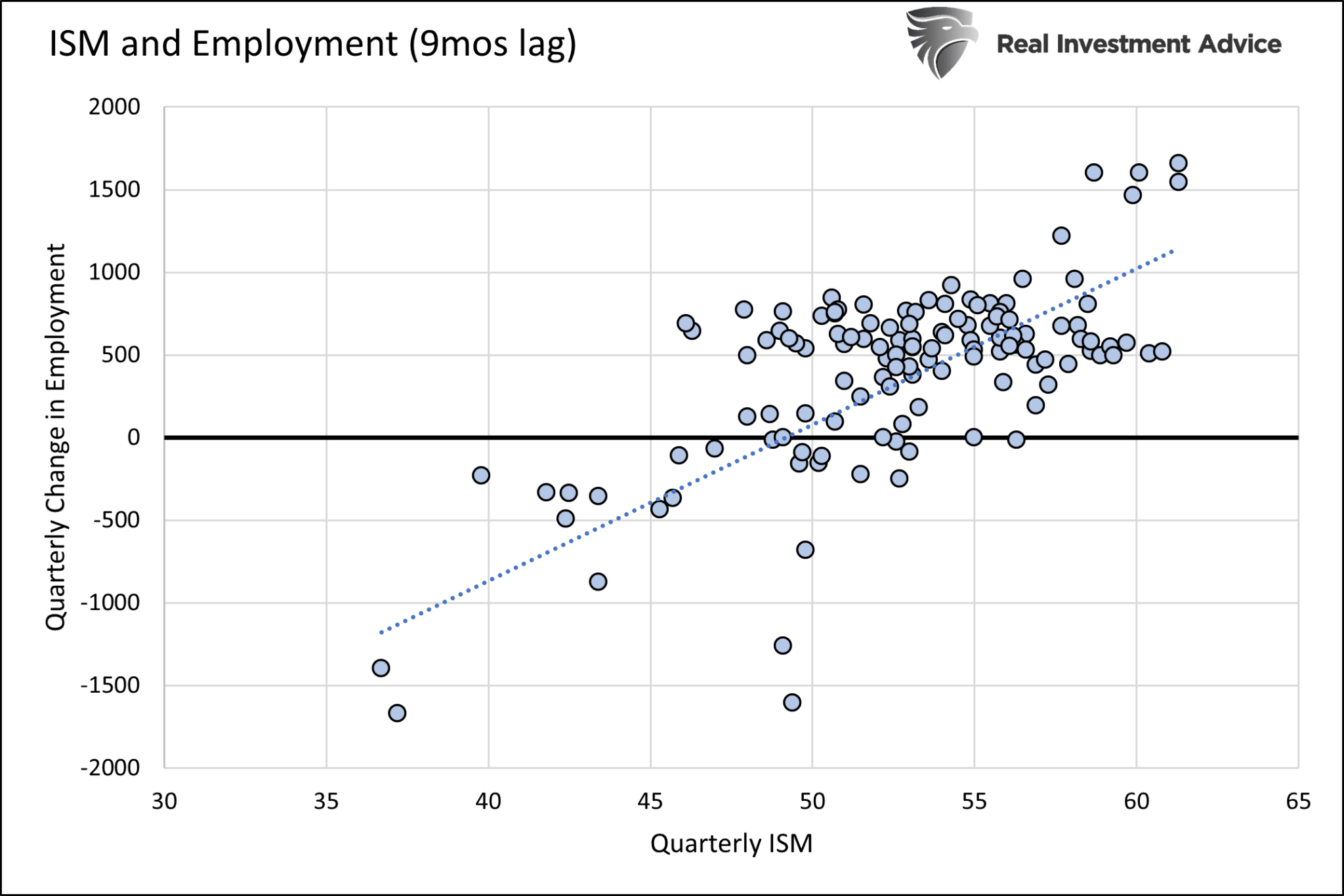

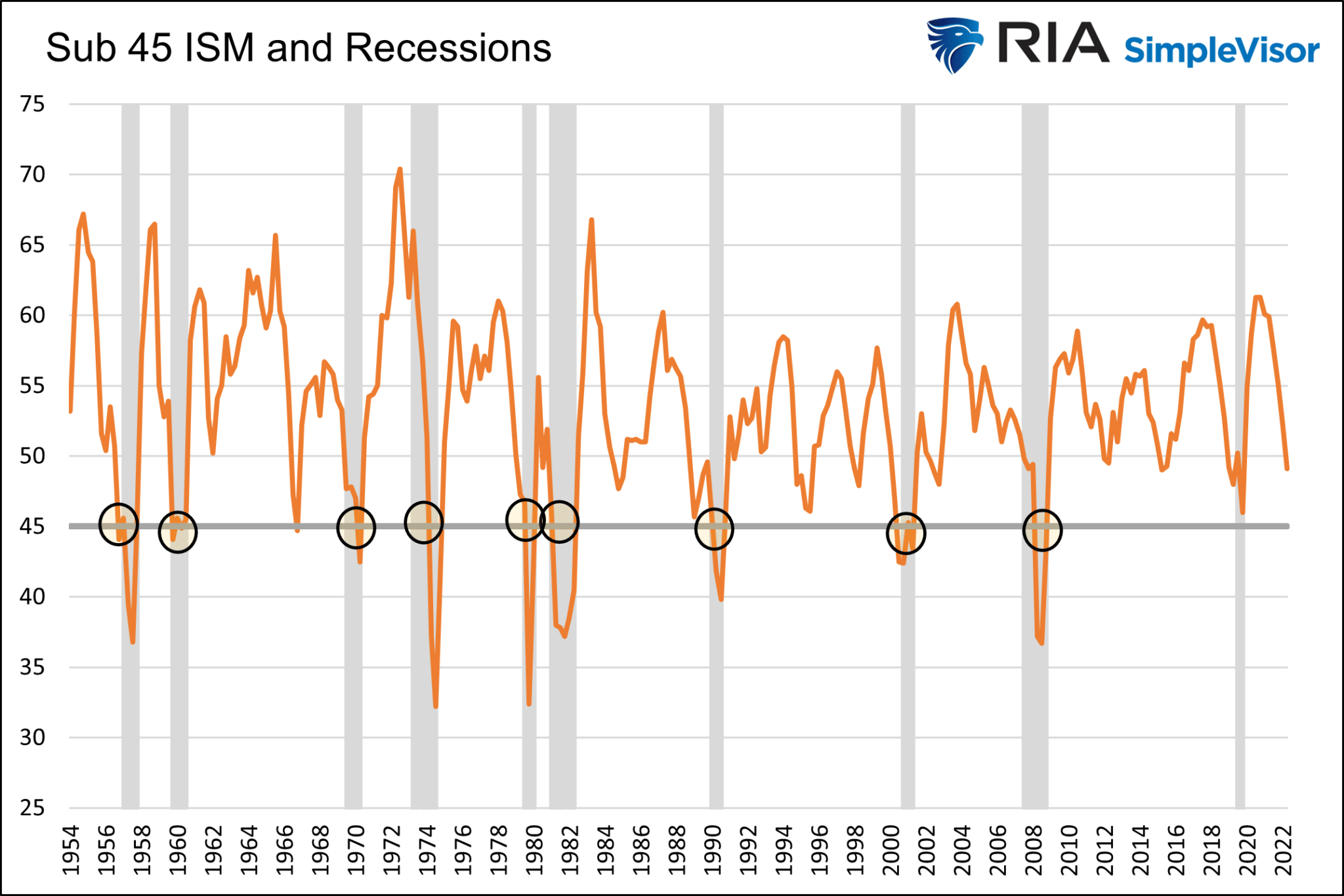

The ISM Manufacturing Index has an excellent track record of signaling recessions. Furthermore, as shown below, it tends to lead employment by about nine months.

The graph above shows that every time ISM has fallen below 45, employment has declined on a quarterly basis. The following chart shows that nine of the last ten recessions were accompanied by ISM below 45. The only time such did not occur was in 2020.

Given the unprecedented and immediate impact of COVID, it’s not surprising a survey of manufacturing executives did not foresee trouble. That said, it was in decline and possibly heading for 45, even if the pandemic never occurred.

ISM is currently at 47.4 and in economic contraction territory. It has been trending lower for over a year, albeit from very high levels. The trend and recent readings warn that a sub-45 level may not be that far off.

NBER Lags

The model we created above can lag the NBER by a few months. While that may seem like a risk, understand that the NBER waits nine to twelve months for revised economic data before ruling a recession. Therefore, while the model may be a little late, it will still be early compared to the NBER. Further, we can use tools like ISM and other leading indicators to help stay ahead of income and employment trends.

Summary

This model is just one of many tools we use to help guide our investments. It is not perfect, but it provides more than a rule of thumb that has previously hoodwinked investors.