Leo Tolstoy wrote that all happy families are alike, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Much the same is true of economies. Maybe that was what EU Commission President Jose Barosso had in mind when he said recently that, “it is a completely different situation in Cyprus and in Slovenia.” Different, but in many ways no less dangerous. For those struggling to keep up with the ever-evolving euro crisis, here are some of the key ways in which the impending crisis in Slovenia differs from—and resembles—the others.

The macroeconomic context

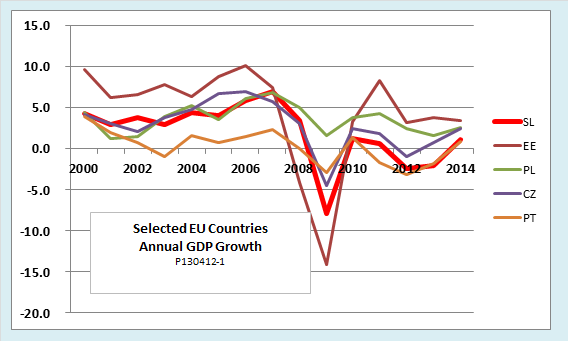

As in many other countries, the crisis in Slovenia, which now centers on the banking system, has developed against a background of broader macroeconomic problems. Not long ago, Slovenia’s economy was doing well. The country was one of the ten that entered the EU in 2004. Like others in its cohort, it initially enjoyed rapid economic growth. The following chart, which compares Slovenia’s economic growth since 2000 with selected other countries, shows that before the global financial crisis, Slovenia looked a lot like Poland, one of the EU’s biggest success stories. Since the crisis, it has looked more like Portugal.

What accounts for the shift from success story to problem case? Although many factors were at play, two were especially significant.

One factor was exchange rate policy. Beginning in 2005, Slovenia held its currency, the tolar, within a narrow trading band against the euro. In January 2007 it abandoned the tolar altogether to become the first of the new member states to officially join the Eurozone. On the whole, the new members with floating rates (illustrated by Poland and the Czech Republic in the chart) had a relatively easy ride through the initial phase of the crisis because nominal depreciation could absorb some of the shock. For example from mid-2008 to early 2009, the Polish zloty depreciated some 30 percent against the euro in nominal terms, helping give Poland the distinction of being the only EU member to avoid a recession. The Czech koruna depreciated by 17 percent over the same period, moderating the recession there. By comparison, euro members Portugal and Slovenia, along with Estonia, which was firmly locked to the euro by its currency board, suffered deeper initial downturns.

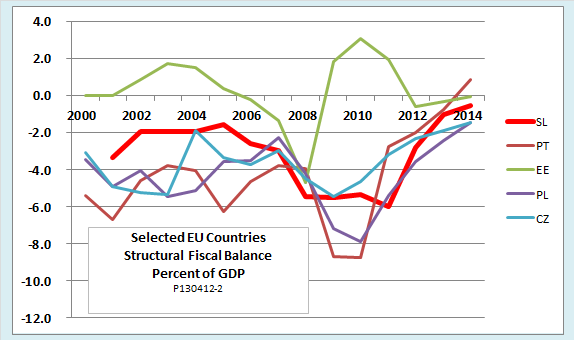

Another key macroeconomic factor was fiscal policy. One measure of a country’s fiscal policy stance is its structural fiscal balance, that is, the surplus or deficit that its government budget would have if its economy were operating at full employment (or more precisely, at potential real output). A move toward deficit in the structural balance indicates fiscal stimulus, whereas a move toward surplus—what economists call fiscal consolidation—indicates fiscal restraint.

The following chart shows structural balances for the same five countries. Estonia, together with its Baltic neighbors Latvia and Lithuania (not shown) took strong fiscal consolidation measures as soon as the crisis hit, making their recessions even deeper than they otherwise would have been. The other countries shown all applied a greater or lesser degree of fiscal stimulus. The stimulus phase lasted longest in Slovenia, which did not begin consolidation until 2012. The stimulus no doubt moderated the initial downturn, but it also caused a sharp increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Slovenia’s debt ratio, which as recently as 2007 was just 30 percent, is expected to rise above the EU’s permitted threshold of 60 percent by the end of this year.

In short, as Slovenia faces a worsening banking crisis in the midst of a double-dip recession, it finds itself with very little macroeconomic room to maneuver. Unlike Poland or the Czech Republic, it cannot rely on exchange rate flexibility to absorb further shocks to its economy. Unlike the Baltic States, which swallowed their prescribed dose of austerity medicine early, it is up against the EU debt limit. And that is not all.

The available policy options are further constrained by growing public protests against austerity, which contributed to the collapse, in January, of Slovenia’s previous government. The new government led by Alenka Bratusek has been reduced to making vague promises to pursue economic growth and fiscal consolidation without hampering the expansion. So far, those promises have not fully satisfied the protesters. One of them, who recently marched with a banner reading, “We are not right and we are not left but we are the people who are sick of you,” told a reporter for Reuters that “the incoming government has the same structure, the same principles as the old one, so we need a new election and we have to vote out the parties that are in parliament at present.”

Structural and governance problems of Slovenia’s banking system

Slovenia is neither an island nor a tax haven. Its banking system is relatively small by European standards. The ratio of banking assets to GDP, which is around 180 percent, is only about a third of the Eurozone average and far less than the ratios approaching ten to one of countries like Cyprus, Ireland, and Iceland. Unlike Ireland or Spain, Slovenia did not have a big housing bubble, and unlike Cyprus, its banks did not speculate in Greek bonds. Nevertheless, Slovenian banking has some serious problems of its own.

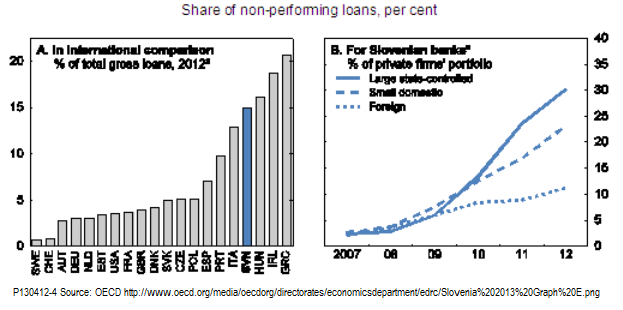

One of the biggest is that Slovenia’s largest banks have remained under state control. As a recent financial system stability assessment from the IMF notes, the large, state-controlled banks have not been well run. They have consistently had lower rates of returns on assets and equity than smaller domestic or foreign banks operating in the country. Also, as the following chart shows, Slovenian banks as a whole have one of the highest nonperforming loan ratios in Europe. Loans to the corporate sector, which is among the most heavily indebted in Europe, are a particular problem, especially loans to construction companies. Not surprisingly, these nonperforming loans are disproportionately concentrated in state controlled banks.

No doubt some of the nonperforming loans reflect garden-variety bad business judgment—the lure of low interest rates, the belief that any boom, once started, will go on forever, and so on. However, the fact that the bad loans are concentrated in state-controlled banks suggests that there may be more to the story than that. Using typically circumspect language, the IMF assessment refers to “long-standing governance weaknesses” and a need for “reducing government influence on the day-to-day operations and lending decisions of banks.” Protesters on the street see the problem more starkly as one of corruption.

True, by broad measures, Slovenia is only moderately corrupt. Transparency International’s 2012 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Slovenia 37th out of 174 countries surveyed. Only Estonia has a better corruption rating among the EU’s new member states, and Slovenia ranks higher than Italy (72) and Greece (94) among the 15 older members. However, looking more closely at the details behind the overall index, we see that some aspects of corruption are more problematic than others. For example, only 4 percent of Slovenians report having personally paid a bribe in the past year, compared to 16 percent of Greeks and 24 percent of Russians. That is all well and good. However, TI’s public opinion data show that political parties, parliament, and the business sector are viewed as more corrupt than other institutions. Furthermore, 75 percent of those asked believe that corruption has been getting worse.

The protesters who brought down the government in January were angered not only by austerity measures but also by corruption scandals that involved high officials. The problems are not unconnected. On the one hand, with austerity pinching everyone’s income, people are doubly angered if they find out that insiders have been getting fat at the public trough. At the same time, to the extent that corrupt mismanagement has weakened the financial system, it is partly responsible for the forced austerity the country is now facing.

Slovenia has an independent Commission for Prevention of Corruption that has exposed some serious abuses. For example, last winter, it found the then Prime Minister, Janez Janša, unable to explain the source of some €200,000 in unreported assets and expenses. It also uncovered evidence that he had purchased some of his real estate holdings with funds indirectly provided by construction companies that had major government contracts. The commission made similar findings against Ljubljana mayor Zoran Janković—€2.4 million in unreported assets and “several financial chain-transactions between the companies owned by Mr. Janković’s sons and companies doing multi-million businesses with the city.” Were any of these transactions channeled through state-controlled banks or facilitated by loans made on favorable terms? It would be more surprising if they were not than if they were.

What will happen next?

The IMF sees strengthening of the financial condition of Slovenia’s banks, followed by their privatization, as the government’s top priority. Citing a 2011 stress test, its most recent financial stability assessment estimated that a double-dip recession scenario—hypothetical in 2011 but now a reality—would require recapitalization in the amount of 5 percent of GDP. A more recent report based on a March 2013 staff visit raises the estimated capital shortfall to €1 trillion, or more than 11 percent of GDP.

The government has made some progress in establishing a framework for resolution of the crisis. In October, it set up an asset management company (AMC) to take nonperforming assets off of bank balance sheets. The AMC is to conduct a “carve-out,” that is, an operation that moves nonperforming assets of banks to the balance sheet of the AMC and replaces them with instruments that carry government guarantees. Such an operation immediately improves bank liquidity, since the beneficiary bank can use the new state-guaranteed assets as collateral for further borrowing. A carve-out can also increase the banks’ regulatory capital by replacing impaired assets that carry high risk weights for new assets with lower risk weights. (See here for a detailed explanation of risk-weighting and regulatory capital and here for a further discussion of carve-outs and other methods for rescuing failed banks.)

Will it work? A lot depends on how competently and honestly the AMC carries out its mandate. For example, among its other powers, it will have the ability to convert nonperforming corporate loans to equity, thereby restoring some corporations to solvency under the AMC’s full or partial ownership. Properly used, that power could strengthen the financial system, but it could also be used to shield well-connected individuals from the consequences of past corrupt or incompetent actions.

Even under the best of circumstances, the problem would remain of how to fund the recapitalization. Liabilities of the AMC are liabilities of the government, so any carve-out immediately increases the government’s total debt. If the AMC acquires nonperforming assets at a price higher than their book value, which would be necessary if the operation is to increase the bank’s common equity, the operation becomes more expensive still. If the terms of the carve-out are less advantageous, the operation could still leave banks with a capital shortfall that the government would have to make up in some other way, also adding to its debt.

As the IMF points out, Slovenia appears to have fallen into a vicious circle. A weak economy is threatening the solvency of the corporate sector. Insolvent corporations are unable to repay loans. Nonperforming loans are eroding bank capital. At the same time, weaknesses of the economy and the financial system mean that the government, which has already borrowed to the limit, has limited access to international financial markets for the funds it needs to recapitalize the banks.

What can be done to break out of the vicious circle? The IMF’s March memo holds out hope for a “clear and coherent plan” that could quickly restore access to international capital markets. As part of that plan, it envisions a fiscal policy that would “continue to reduce the structural deficit, while letting the automatic stabilizers work.” (Translation: move the structural budget incrementally toward surplus by cutting back the country’s welfare state while allowing the current deficit to rise as the economy sinks further into recession.) Unfortunately, Prime Minister Bratusek has not yet tabled the requisite clear and coherent plan.

If private lenders turn out to be unwilling to lend Slovenia the funds it needs to restructure its financial system and keep its government running, some other source will have to be found. One possibility would an Irish-style bailout in which the EU loans the Slovenian government enough funds to recapitalize its banks while fully protecting depositors and senior creditors. That would ultimately transfer the burden of restructuring to Slovenian taxpayers. They might not take kindly to the prospect, especially if some of the protected depositors and creditors were political insiders or their friends.

Alternatively, the EU might follow through on its latest theory that taking away the risk from the financial sector and putting it onto the public shoulders is no longer the right approach. Doing so would mean a Cyprus-style bail-in under which the EU would say to uninsured depositors and unsecured creditors (in the words of Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem), “Look, where you take on the risks, you must deal with them. And if you can’t deal with them, you shouldn’t have taken them on and the consequence may be that it’s end of story.” The problem is that EU authorities might not have the nerve to carry repeat that approach, fearing that using it too often could lead to a break-up of the Eurozone itself.

Meanwhile, markets are increasingly calling into question Slovenia’s ability to refinance its existing debt, let alone take on the burden of bank restructuring. Yields on 10-year government bonds have jumped from 2.16 percent at the beginning of the year to 6.62 percent last week. The cost of credit default swaps has soared. Last Monday, the government tried to sell 100 million euros in Treasury bills, but managed to raise barely half the desired amount. The story has not yet played itself out. Stay tuned.

Original post

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Slovenia Is Not The Next Cyprus; That Doesn’t Mean It’s Not In Trouble

Published 04/15/2013, 02:01 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Slovenia Is Not The Next Cyprus; That Doesn’t Mean It’s Not In Trouble

3rd party Ad. Not an offer or recommendation by Investing.com. See disclosure here or

remove ads

.

Latest comments

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2024 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.