President Obama has a major bone to pick with China – and it boils down to what is known as the “ratchet effect.”

The term refers to an escalation in production or price that tends to self-perpetuate. In the case of China, it’s all about production – that there’s way too much of it.

In fact, during its annual talks with Chinese government officials, the Obama administration has decided to take the opportunity to push for cuts in excess Chinese industrial output – something that has flooded global markets with discounted products.

This surplus – particularly on a number of commodities such as aluminum and iron ore as well as manufactured goods – is provoking anger from producers, unions, and politicians alike.

Officially known as the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, this discussion between the U.S. and China is taking place this week over the span of two days. During this annual sit-down, senior American and Chinese officials discuss a broad range of economic, foreign policy, and security concerns.

Dissecting the “Ratchet Effect”

The definition of the “ratchet effect” includes the inherent inflexibility of its outcome – the resultant difficulty in reversing a rise in production.

This rise in production becomes difficult to reverse, mainly, because producers and consumers alike tend to be influenced by the previous best or highest level of production.

In essence, the ratchet effect, like many trends in economics, tends to self-perpetuate, especially when it comes to the production side of the equation.

The ratchet effect may not only impact large-scale firms – in terms of their investments in capital – but influence entire economies, as well.

Whether it’s a widget manufacturer or a government, once it has made new investments, injected capital, and built plants and factories, it becomes difficult to scale back production.

Ahead of the start of the dialogue on Monday, U.S. Treasury Secretary, Jack Lew, emphasized, “Excess capacity is not just a domestic issue,” as it’s causing “distortions in global markets.”

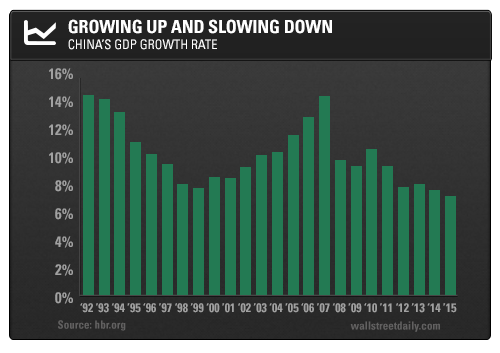

Since 2006, China has increased production of raw materials of all kinds, from metals to energy to grains.

This is not only because China recognized the need to reduce its dependency on foreign goods and materials, but also because it was building an infrastructure whose growth has been unprecedented in our time.

China’s alarming growth was perhaps best displayed to the world during the 2008 Summer Olympics, in which its grandiose performances, costumes, and facilities shocked viewers worldwide.

It seemed as if a modern day Roman Empire had risen to power with extravagance and self-congratulations. In fact, in its years of double-digit growth, new cities in China were popping up faster than the world could count. It was even reported that China was building a Boston-equivalent city every two weeks.

By 2013, China had succeeded in becoming the largest producer and consumer of most global commodities, as well as the number one exporter of goods, in general.

Affecting the Consumer and the Worker

From the consumer angle, similar principles govern the ratchet effect. Once raw materials and the products that are created from them become more readily available and affordable, people’s expectations are heightened, making it difficult for the consumption process to scale back.

This is the case with China.

China is not only the largest consumer of coal, aluminum, iron ore, and copper, but of an increasingly mind-boggling list of agricultural goods – including rice, wheat, pork, grapes, peanuts, tobacco, paperboard, milk, and even beer, according to the 2013 FAOSTAT, which is a part of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

As China’s overall population has grown, so too has its middle class.

In 2015, China abandoned the one child policy, implemented in 1980, due to its graying demographics, thereby encouraging more consumption of costly goods such as beef and dairy.

Any excess commodities could be exported to a growing middle class in the emerging market world, and to developed nations as well, whose own output is more costly, predominantly as a result of less competitive labor costs – even after factoring in the cost of transport.

And whether it’s working within a business or a country, the ratchet effect has direct implications for labor and wages.

In an effort to avoid any wasted investment in human capital, after hiring and training – it’s difficult to lay off workers or reduce their wages.

In China’s case, keeping its employment rates high and its people at bay has become a priority for the government – especially in light of increasing access to social media as well as uprisings at plants, factories, and farms. Keeping businesses running, even with rising inventories, is seen as preferable to dealing with disgruntled laborers.

Bottom line: Over time, it became difficult for China to justify producing less than the aggressive new standard they had set for themselves.

All of these examples illuminate the dangers of the ratchet effect.

The primary problem is of course that people become accustomed to constant growth, even in industries that have over-saturated the markets with too many goods and not enough demand. Thus the market is no longer satisfying their wants and needs, defeating the overarching purpose of economics.

Well aware of this predicament, Secretary Lew went on to say, “Excess capacity ultimately is corrosive of an economy’s economic efficiency. It means that you have a misallocation of resources.”

Now, China’s economy is faltering and factories are closing, something that has prompted additional concerns that are now shaking global stock markets.

Recently, China has acted in an attempt to strengthen the value of the renminbi, making imports into China more attractive to avoid weakening the currency. This has come about even as the Chinese renminbi is seeing a five-year low against the dollar.

Vague Promises

In response to pressures from the U.S., Chinese President Xi Jinping has said that China will cut back some production at steel mills and coal mines where the capacity far exceeds domestic demand – particularly with an aim to reduce CO2 emissions.

Meanwhile, China is also trying to win official status as a market economy from the U.S. and E.U. in a bid to helping its manufacturers ward off punitive tariffs on exports.

Xi has been facing the production gun for some time. In March, the U.S. levied hefty tariffs on Chinese steel makers for selling below cost, and last month, the Commerce Department raised already-sizable duties on imports of Chinese steel.

But while Xi has made it clear that he is enforcing what he calls “supply-side structural reform” by shifting investments to more rewarding industries, his plans still remain vague.

Much of the excess capacity is still exported abroad in competition with foreign producers who are struggling against China’s cheaper production.

Mr. Lew believes there may be more of a reaction from Beijing as he is putting excess capacity high on the agenda for the Group of 20 (G-20) summit meeting to be held by China in Hangzhou this September. Here, leaders of the major economies will have a chance to discuss concerns regarding the global markets, of which China will likely be a focal point.

With respect to the next U.S. president, many doubt the talks will continue in the same tone with which the Obama administration has interacted with China.

After Chinese government officials announced that the country will continue to support overcapacity in their steel production, Hillary Clinton released a statement condemning the unfair decision as threatening to American manufacturing and jobs. If nominated, she pledged to take on Chinese trade abuses.

And both Donald J. Trump and Bernie Sanders have argued strongly that trade agreements with China have had negative ramifications for American workers.

Yet in the short-term, any encouraging words from Mr. Xi that point to curbing production should have the effect of edging commodity prices higher, even in a glut.

How’s that for the ratchet effect at work?