Commentators often portray the Baltic countries as laboratories for testing the effects of austerity under fixed exchange rates. Although they share many common traits, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia have each followed distinctive paths during the global economic crisis. Estonia maintained tighter fiscal discipline going into the crisis, helping it to win entry into the Euro. Latvia suffered the deepest slump, but it has stuck with its austerity program for better or worse and has recently recorded some of the fastest quarterly growth rates in the EU. This post examines the distinctive elements that Lithuania has added to the Baltic saga.

The Political Situation

Unlike Latvia and Estonia, which re-elected the parties that had led them through austerity, last fall’s vote in Lithuania brought a change of government. The coalition that took office on December 13 consists of four parties. The largest is the Social Democratic Party of Lithuania, led by the new Prime Minister, Algirdas Butkevičius. The Social Democrats had previously led a minority government from 2004 to 2008, leaving office just as the global crisis was beginning. The Labor Party (also a member of the pre-crisis coalition), the Order and Justice Party, and a party representing the Polish minority complete the current coalition. It replaces a center-right government under former Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius of the Homeland Union Party.

The new coalition, which has a strong populist flavor, comes to office in an atmosphere of controversy. The leader of the Labor Party, Viktor Uspaskich, a Russian-born entrepreneur, has been under investigation for tax fraud and his party stands accused of serious financial irregularities. President Dalia Grybauskaitė initially vetoed Labor Party participation in the cabinet. She later relented to allow some Labor Party ministers to be seated, explaining her decision on the grounds that the individuals in question were apolitical technocrats. The Order and Justice Party is also controversial. Whereas the Social Democrats and the Labor Party share leftist views, Order and Justice is seen as populist in a more socially conservative sense. It is led by Rolandas Paksas, a former stunt-flying champion and later president, who was impeached in 2004 for granting citizenship to a Russian businessman suspected of criminal ties. To add to its problems, the new government’s election victory was tainted by charges of voting fraud.

Whether this coalition lasts out its term is an open question. President Grybauskaitė has suggested that it may not. Meanwhile, the new government faces some serious economic challenges.

The Economic Situation

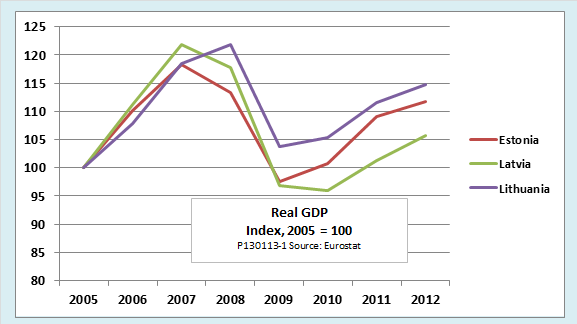

All three Baltic States had a rollercoaster ride through the global economic crisis, with Lithuania faring a little better than its neighbors, as the following chart shows. The pre-crisis boom was fueled by strong capital inflows, both from EU funds and through Scandinavian banks. Much of the incoming credit went into real estate and other non-tradable sectors. In all three countries, strong financial inflows and rapid growth led to real appreciation of exchange rates. Since their currencies were pegged to the euro, this appreciation could not take the form of a change in nominal exchange rates, so it manifested itself through rapid inflation, instead.

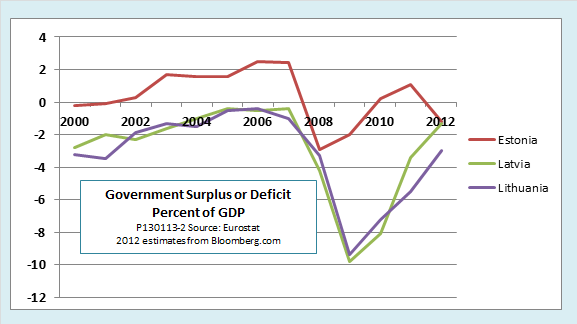

In Latvia and Lithuania, loose fiscal policy aggravated the pre-crisis boom, as detailed in the next chart. True, the budget deficits were small in absolute terms, well within the EU’s 3 percent limit. However, the Baltic economies at that time were seriously overheated, with borrowing and building far above any reasonable estimate of what could be sustained in the long run. Under those conditions, their budgets should have been strongly in surplus, both to moderate the boom and to accumulate fiscal space for future contingencies. Estonia did manage a modest budget surplus and had very little debt, but even so, it was unable to get through the crisis without external help.

In principle, the Baltic countries could have reacted to the crisis by devaluing their currencies, but they chose not to do so. In purely economic terms, there are strong reasons to think that floating exchange rates ease adjustment to external shocks. That proposition finds support in the experience of floating-rate countries like Poland, the only EU member not to undergo a recession, and the Czech Republic, which experienced a relatively moderate downturn. In the Baltics, however, domestic political arguments for keeping the peg to the euro were stronger than economic arguments for floating. Concern for the many Baltic citizens who had borrowed heavily in euros during the housing boom was particularly important.

Instead of floating their currencies, then, all three Baltic States chose the path of internal devaluation. That meant strict austerity, not only to control government spending but also to put downward pressure on prices and wages with the aim of restoring competitiveness.

Unlike Latvia, which turned to the IMF for financial help, and, in doing so, subjected itself to strict international oversight, the Lithuanians did not ask for IMF aid, in the hope of retaining greater freedom to design their own crisis program. In practice, though, their options were limited and their austerity policies ended up being no less severe than those of their neighbors. By the time the crisis hit, the center-right coalition was in power. It promptly raised the VAT, excise taxes, and corporate taxes; cut pension benefits, unemployment compensation, and paid holidays; introduced mandatory health insurance premiums; and began raising the retirement age from 60 toward an eventual target of 65.

In addition to restoring competitiveness, wage deflation was also supposed to facilitate a shift of labor and other resources from non-tradable sectors like construction to tradables like manufacturing, farming, and forest products, allowing an export-led recovery.

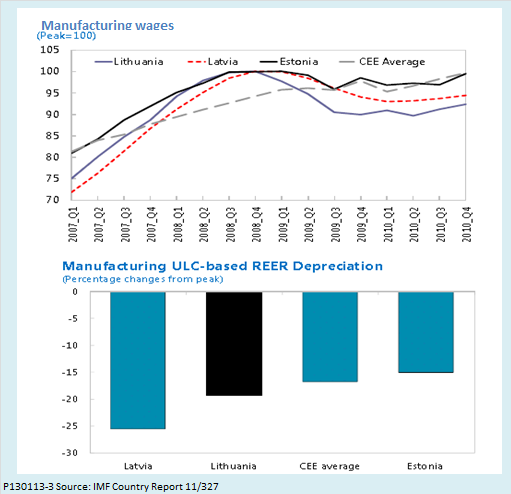

The next pair of charts, taken from an IMF country report, show that internal devaluation strategy did have at least some of its intended effects. Internal devaluation brought down manufacturing wages and also reduced unit labor costs, which reflect changes in both wages and productivity. Lithuania achieved an impressive 20 percent reduction in unit labor costs, although Latvia, where wages decreased less but productivity increased more, did even better.

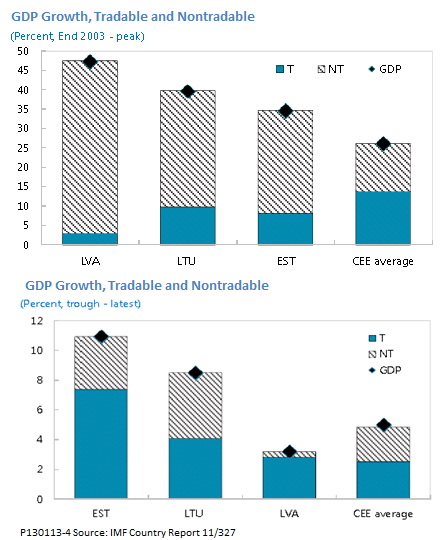

The final pair of charts show that internal devaluation succeeded in shifting resources from non-tradable goods to tradables. During the boom, the tradable sector accounted for only about 20 percent of real output growth in Lithuania. As the economy recovered, that share rose to about 40 percent. The shifts from non-tradables to tradables in the Baltics stands in sharp contrast to the average for Central and Eastern Europe, where the shares remained roughly constant.

The Challenges Ahead

In sum, it appears that the Baltic strategy of internal devaluation has been partly but not fully successful. It did not prevent a sharp contraction during the crisis; in fact, it appears to have aggravated it, as compared to the floating rate countries of Central Europe. The policy did achieve a significant real devaluation, allowing exports to lead a robust recovery. Real GDP is not yet back to its pre-crisis peak, but the structure of GDP looks more sustainable than it was at the peak of the credit-fueled construction boom. Real GDP per capita is higher than before the crisis, but only because of substantial emigration, which, together with an aging population and a low birth rate, creates an unfavorable demographic situation.

Unemployment remains uncomfortably high. In Lithuania, it was 12.5 percent as of November 2012, down from its peak of 18.3 percent. Unemployment in Latvia is a couple of points higher. In Estonia, the rate is 9.5 percent, a rate that looks good only in comparison to the EU average of 11.7 percent. To put matters in perspective, the unemployment rate in Lithuania had briefly dipped below 4 percent just before the crisis, and was only a little higher in Latvia and Estonia.

Looking ahead, the Lithuanian economy faces major challenges. During the 2002-2007 boom, real GDP grew at a rate over 8 percent. Now, according to the IMF report cited above, growth is expected to fall by as much as 5 percentage points. About 2 percentage points of the decrease simply reflects the fact that pre-crisis growth was unsustainably rapid. The rest is due to lower investment, slower growth of trading partners and the fact that growth tends to slow as income levels rise.

In the view of the IMF staff, Lithuania will need to press ahead with structural reforms to sustain even that reduced rate of growth. The previous government made some progress in reforming state enterprises, education, and pensions, but the incoming government may find it hard to maintain the momentum. Indeed, it is already threatening to reverse some educational reforms and has announced an increase in the minimum wage. Although perhaps justified as a response to the effects of the crisis on living standards of low-wage workers, the wage increase could undermine hard-won gains in competitiveness. In addition, the IMF sees a need to make the business environment friendlier, simplify overly complex regulations, and improve conditions for small businesses.

Beyond these tasks, the new government faces a difficult problem of national energy policy. As a condition of entry into the EU, Lithuania shut down a Soviet-era nuclear plant that had supplied most of its electricity. Now it is dependent almost entirely on Russia for both electricity and gas. The outgoing government favored construction of a modern nuclear plant to replace the old one, but the opposition preferred seeking less costly alternatives. The nuclear project was put to a nonbinding referendum at the time of last fall’s elections, and lost by a two-to-one margin. Options are limited. The new government is talking about an LNG terminal to bring in gas and a crash program of energy upgrades for aging Soviet-era apartment buildings. It has not completely ruled out a new nuclear variant. It is far from clear, though, where the funding would come from for any of these.

The bottom line is that the new government will have a hard time meeting the economic challenges it faces. It inherits an incomplete recovery from a crisis that it did nothing to prevent during its last turn in power. It has raised populist expectations that may undermine its ability to implement further structural reforms. After encouraging voter rejection of the nuclear alternative, the new government has no convincing alternative energy plan. Its ability to deal with all of these issues risks being undermined by the distractions of legal actions and corruption allegations.

The new coalition has only been in power for a month. In fairness, it should be given a chance, but there is no doubt it has its work cut out for it.

Thanks to Sarunas Merkliopas, who served as a research associate for this post.

Original post

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

What's Ahead For Lithuania?

Published 01/15/2013, 01:45 PM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

What's Ahead For Lithuania?

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2024 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.