Following the explicit path of orthodox monetary and economic theory delves into something very much like Lewis Carroll’s monstrous rabbit hole he devised for Alice all the way back in 1865. Like the story’s Wonderland, the other side of the hole leads to some version of nonsense that seems to project, in the book’s case, the reader’s own senses. In economics and especially econometrics, the boundary to Wonderland is rational expectations.

The theory is simple enough, even intuitively so. Broadly speaking, rational expectations theory asserts that economic or market agents will act today on expectations of tomorrow. It is positively basic and so much so that it seems inarguable; but that is not the extent of it, as rational expectations leads in all sorts of directions once you follow the white rabbit of dominant theory.

Start with “forward guidance”, for instance. The current iteration of the term in use under Janet Yellen’s FOMC is not much like the version that preceded it. The former, under Bernanke’s regime, was closer to the original. While today we are supposed to believe forward guidance is something like the comical dot plots that accompany each and every (wrong) FOMC projection, what forward guidance in its native setting applies is much more convoluted (and appropriate for this examination).

If markets act according to rational expectations theory, then QE would never work; it couldn’t. The very act of suggesting QE would be its own undoing. In other words, if markets are fully rational and efficient, then they would expect QE to work and therefore would act today as if QE had already interjected its effects before it ever did anything (in anticipation; expectations). Since QE is supposed to work by lowering interest rates hard against the zero lower bound, rational market agents would instead sell bonds expecting higher interest rates in the future where QE dominates. Thus, interest rates would rise at the outset where policy intends that they fall.

Forward guidance was invented, quite literally, as a means to thwart rational expectations of, well, rational expectations. Paul Krugman in 1998 argued against the Bank of Japan not because he was against the forthcoming ZIRP but rather because he didn’t think it could overcome this initial contradiction. Dr. Krugman wanted BoJ to “credibly promise to be irresponsible” so that markets would have no choice but relent up front to the intent rather than act on future expectations.

For QE to work, then, it has to convince markets that it won’t work (because rates have to fall, which signals, on the whole, that the future is bleaker) but only so much as it can plausibly maintain that it will work at some distant point far enough in the future that investors won’t act as if it will right from the start. That was the whole idea behind Bernanke’s final version of forward guidance, as he promised initially in 2012 that QE3 and QE4 would be “open ended” (Krugman’s “credibly promise to be irresponsible”) and large but then tied to the unemployment rate. In other words, the Fed would force down interest rates but only until the fruits of low interest rates were demonstrated.

Unfortunately for him, the Fed’s economists did not anticipate the collapse in labor participation that artificially quickened the championed “improvement” in the published unemployment version ,which meant expectations all over were entirely messed up and not that far into the program. That meant, in the summer of 2013, investors were back to rational expectations where Bernanke’s promise of being tied to the (published) labor market were taken as true despite his protestations against it; and so interest rates rose before he was ready for them to, and they did so in rather violent and global fashion. From a theoretical standpoint, what was monetary policy projecting in the summer of 2013?

Bernanke said that he wasn’t going to tighten but also that there were signs QE was working perhaps faster than expected. Those positions aren’t necessarily at odds with each other, but in the world of economics dominated by expectations they were contradictions and taken as such. Much of the policy confusion and reluctance since that point can be traced to this root. That is especially true as since that point interest rates have again done the opposite of what was intended – rates, in general, rose during QE and fell after it.

These kinds of inherent contradictions suggest something else entirely about the theory itself, which undoubtedly owes to the very conditions (and reasons) that birthed rational expectations in the first place. While it sounds like something developed out of pop psychology, its genesis was purely mathematical.

In 1972, economist Robert Lucas was working on the theoretical notions of inflation and monetary settings developed by Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps (ironically in refuting the Samuelson and Solow attempt at economic control through the “exploitable Phillips Curve”), in particular the pursuit of the generations-old goal of mathematically calculating a general equilibrium view of money and economy that included and harmonized every important variable. Quantity theory had always been part of the discussion but with technological advances in the 1950’s and 1960’s econometrics started to seem truly possible. Among the required steps were more developed statistics and equations.

What Lucas did, in his famous 1972 paper Expectations and the Neutrality of Money, was to assume generalized equilibrium from the very start. Departing from a regime of “adaptive expectations” Lucas asserted “rational expectations.” What that meant was neutralizing the equations of price expectations so that the difference between actual and expected prices is thus set to zero. In that sense, price behavior could then be adapted under a general equilibrium format, and the whole set of Freidman/Phelps “natural unemployment rate” econometrics would balance (I am simplifying here intentionally).

The implications of such a mathematical breakthrough were striking and recognizable in the aftermath of the Great Inflation. The most direct interpretation, and the one at which modern and 21st century economics turns, is that “rational expectations” will lead to models in which quantitative monetary policy prescription and evaluation can be made. This is perhaps most well-known in the “rules-based” paradigm of monetary alternatives, such as the Taylor rule, but also forms the central theory even behind QE (especially the “Q”).

The problem, as with quantum physics, is that “rational expectations” is not a real world phenomenon and certainly not directly relatable or transferable. It sounds as if it may be consistent with our experience of economic reality, as setting the differential of actual and expected prices to zero represents something like total market efficiency. It means that “market” prices are always correct and therefore econometric models need not concern themselves about initial equilibriums – they are always just assumed to be in that state. Inside the math, market prices are thus presupposed to always be market-clearing, and thus not subject to stochastic tests.

If we are forced to assume that all market prices are correct and efficient, and all market prices such as the UST or eurodollar curve price only very nasty times not just immediately ahead but into the intermediate future as well, then rational expectations is forced to reckon with QE as itself a total failure. That was the appeal of stock prices for so long, as they were at one point the only market-based concurrence (especially after the events of 2013) of what monetary policy expected markets to expect. Since stock prices have stopped conforming, policy must explain both what changed and why it no longer has any markets (assumed to be full efficient) confirming its curiously unchanged narrative.

To further break down stocks as expectations, you are forced to conclude that they surged especially after QE3 in anticipation of economic circumstances that were to come but not at that time apparent – as forward guidance. And then just when it looked like growth was possibly about to turn in the long-awaited direction (middle of 2014), stocks stopped rising. In other words, from the get-go stocks indicated the recovery policy wanted but then when it seemed very close to being realized (5% GDP and all that) stocks suddenly flipped to signaling only trouble – the very “financial turmoil” that now paralyzes Janet Yellen’s bland and watered down forward guidance. Worse, that updated position in equities only brought them into conformance with the view from credit and funding (and commodities) that had been in place almost the entire time. From the standpoint of monetary policy, everything is backwards.

The bigger problem as you might notice from the focus of all this discussion is the absence of inflation and the real economy, with attention perhaps too much devoted to markets as an economic intermediary. The simplest version of inflation expectations involves no markets at all, namely that people and businesses view the “credible” threat of money printing as inflationary and thus work in anticipation today without waiting for confirmation of that threat. The emphasis on markets, then, is to assess the credibility of “money printing”, which suggests where all this has gone awry.

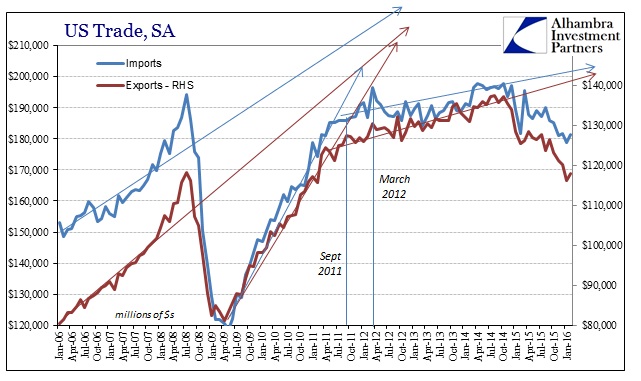

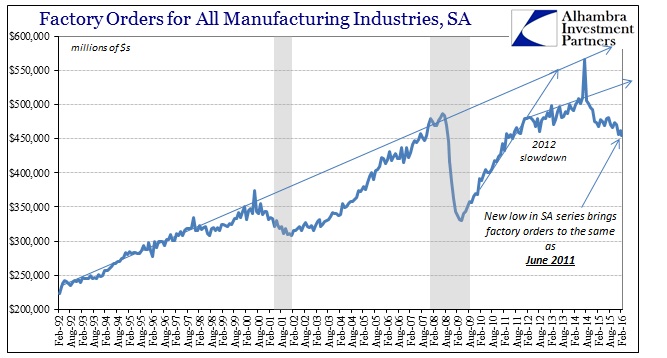

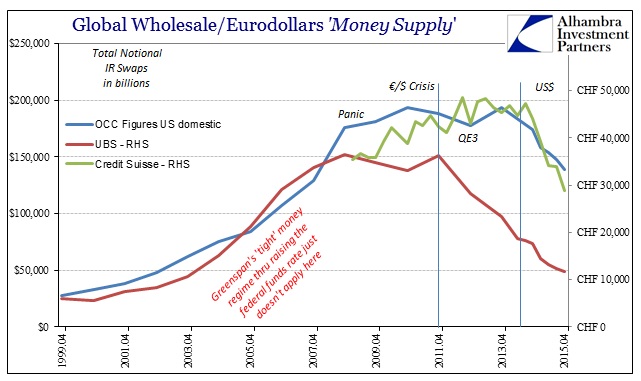

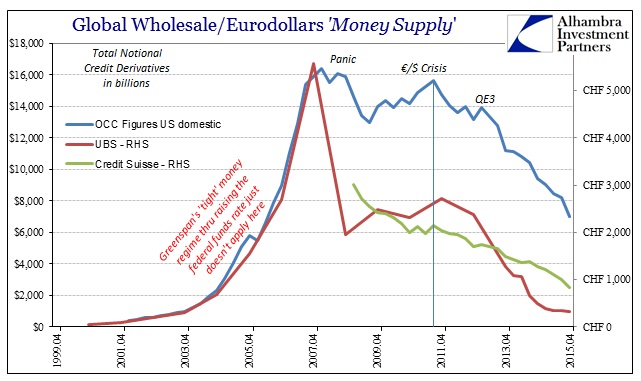

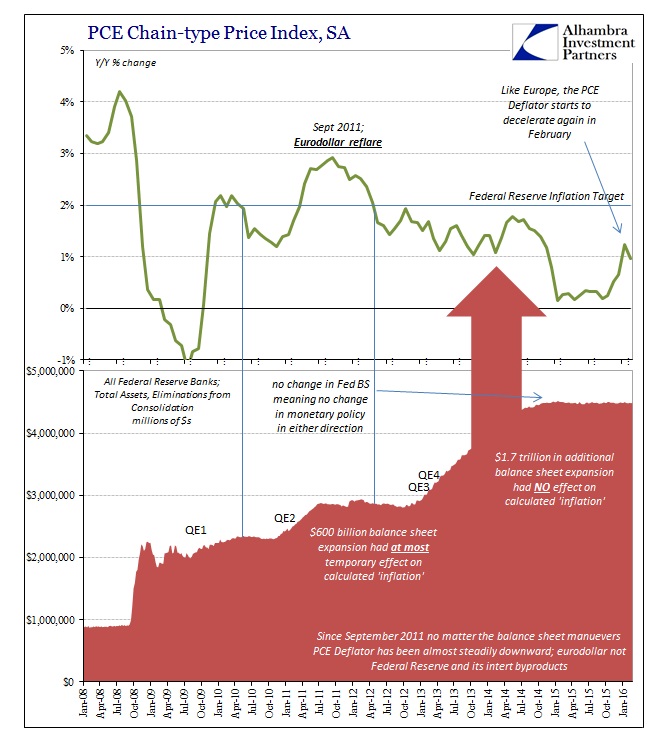

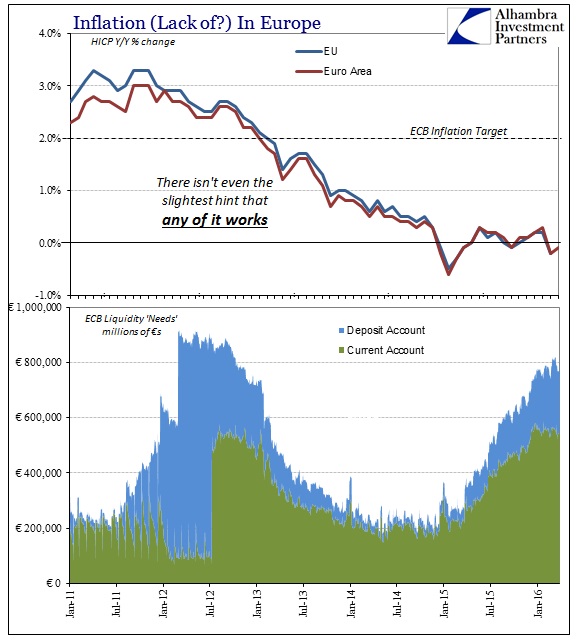

No matter how stocks reacted to the QE’s, commodities and real economic circumstances only seem to have followed the first one – maybe the second. By the third, “credible” seems to have shifted to something else, which is why you can plainly see QE2 having some effect on calculated inflation, for example, but only for a short time; and then QE3 and QE4 have none at all. What happened between QE2 and QE3 is the same as we find all over the world – the eurodollar shift in 2011.

It actually makes sense in terms of expectations just not in the academic version of rational expectations as a plugline to make a system of equations compute. In other words, there is a great deal of evidence to support the idea of the power of expectations in both financial and economic settings, but that monetarists and policymakers make too much of their own role in those determinations. That might have been especially true of the events in 2011 which suggested (perhaps even so far as proved) only impotence. From that perspective, the financial and economic circumstances that have occurred since (eurodollar decay; slowdown that won’t stop slowing down) actually make perfect sense.

QE3 wasn’t taken as a “credible promise to be responsible” where QE2 might have been (and even then doubts had already started to intercede) but rather confirmation in the real economy that neither of the prior two actually worked and thus it might make sense to anticipate and prepare for a world where central bank promises are irrelevant. In raw banking, it was a step further as ratification that the dollar system, which was in a very precarious state since the panic, was simply not salvageable. Even stocks, which had a different view of QE3 and its potential, have instead been mugged by the “dollar” to conform far more to the pessimistic view, rejecting the very idea of rational expectations to begin with.

The participation problem of the labor market “wins”, thwarting not just Bernanke’s forward guidance but the whole idea of “money printing.” It offers very compelling evidence that QE was never anything but illusion; the real economy can be moved by illusion, that is the nature of expectations, but only for so long and only as far as the deception is never actually revealed. That was 2011 in a lot of places, and the doubt has only expanded since then.

In the Wonderland of orthodox economics, this all requires policymakers to continue to chase their own tail as if that were a goal worthy of effort; it never leads anywhere and in fact, owing to rational expectations theory in the first place, can never lead anywhere. Unlike economics and all its wonderful and elegant DSGE models, the real economy is never obliged to view monetarism as credible at anything. That doesn’t mean, however, that expectations are never fulfilled or met. Greenspan was once the undisputed maestro; Bernanke an arguable but somewhat accepted hero; nobody can quite tell what Janet Yellen is talking about, only they are sure she’s not sure she knows either. The difference in interpretation between them is not personality. You might even say that it is just rational progression, as the more central bankers actually do the less expectations are impressed.