Anti-Vigilantes

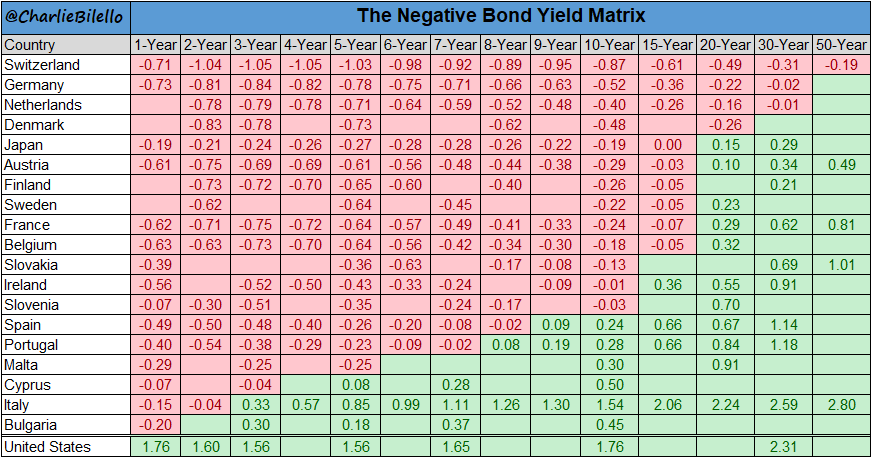

We dimly remember when Japanese government debt traded at a negative yield to maturity for the very first time. This happened at some point in the late 1990s or early 2000ds in secondary market trading (it was probably a shorter maturity than the 10-year JGB) and was considered quite a curiosity. If memory serves, it happened on just one brief occasion and it was widely held at the time that the absurd situation of a bond buyer accepting a certain loss if the bonds were held to maturity was an outlier, never to be seen again. And this is what the world of bonds looks like today:

Sovereign debt with negative yields to maturity rises to a new record high of $15 trillion

As the chart indicates, a trillion isn’t what it used to be, since lately another trillion in negative-yielding debt seems to be added to the pile every other week. Falling inflation expectations, the widely expected resumption of “QE” by major central banks (chiefly the ECB), speculative buying and regulations enforcing financial repression have all combined to drive “investors” (we use the term loosely in this case) over the cliff into the realm of utter madness.

With respect to regulations and financial repression, Charles Gave of Gavekal Research related the following anecdote in a recent missive (hold on to your hat):

When meeting some clients a few weeks ago in Amsterdam, I made my usual remark about the stupidity of running negative interest rates. In response my host told me a sobering story. He manages a pension fund and had recently started to build large cash positions. One day he was called by a pension regulator at the central bank and reminded of a rule that says funds should not hold too much cash because it’s risky; they should instead buy more long-dated bonds. His retort was that most eurozone long bonds had negative yields and so he was sure to lose money. “It doesn’t matter,” came the regulator’s reply: “A rule is a rule, and you must apply it.”

Thus, to “reduce” risk the manager had to buy assets that were 100% sure to lose the pensioners money.

You can read the rest of Mr. Gave’s article here. As he points out, the long-term management of savings by pension funds, banks and insurance companies is essentially doomed to failure by negative yields. It cannot be otherwise: someone is eventually going to take the losses – that is an apodictic certainty. The only question is whether these losses will be incurred sooner or later.

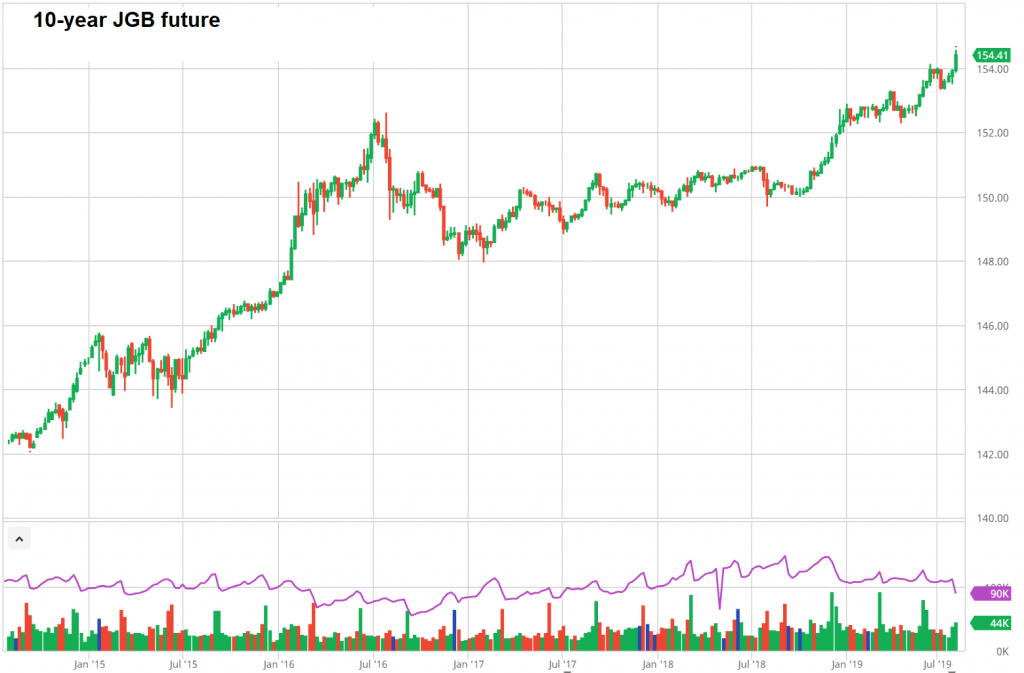

A friend recently asked whether the situation depicted above should be considered the “new normal”. Historically, long term bottoms in interest rates have tended to be quite drawn-out affairs. As the case of Japanese government debt demonstrates (the original “widow-maker”, so called because it has destroyed countless traders who tried to bet against the uptrend in JGBs over the years), if a central bank is strongly committed to manipulating bond prices, they can trade at extreme levels for years on end.

JGB futures contract, weekly – the original “widow maker”.

Having said all that, we believe that negative-yielding bonds very likely do not represent a “new normal”, i.e., an immutable state of affairs that will remain with us forever. In fact, there are very good reasons to believe otherwise. First, here are a few more charts of major sovereign bonds and their yields:

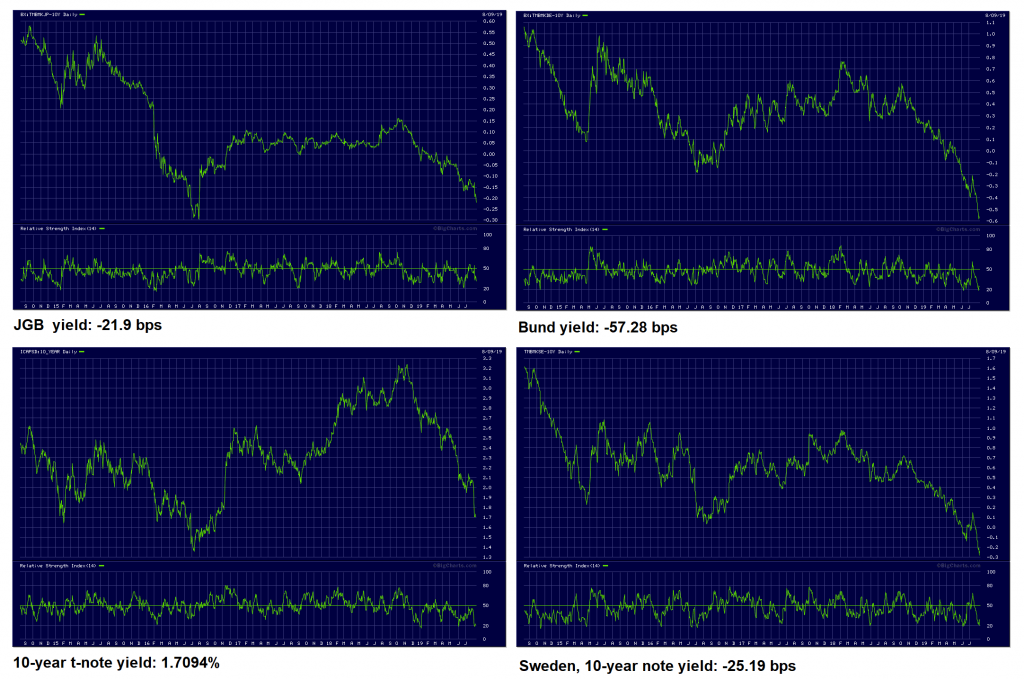

German Bund futures and 10-year US t-note futures (weekly). T-notes still trade at a positive yield of ~1.7%, which makes them a relative bargain compared to Bunds – which trade at a negative yield to maturity of nearly 60 basis points (a new record). In fact, the entire German yield curve out to the 30 year maturity has declined into negative territory.

Yields on 10 year government debt: JGBs, German Bunds, US t-notes and the Swedish 10-year note. Sweden’s Riksbank was the first central bank imposing negative interest rates on bank reserve deposits.

From a technical and sentiment perspective, bond prices and yields have reached rare extremes in the short term. It probably won’t take much to trigger a sizable correction. Note that due to the convexity effect very small moves in rates have an outsized effect on prices – both to the upside and to the downside.

As mentioned above, the main question is not whether losses will be incurred, but when it will happen. Who will end up holding the bag? In some shape or form, all of us will. After all, when pension funds, banks and insurers lose money, their clients are bound to suffer as well.

That is far from the only problem. Our readers have no doubt noticed that the massive central bank interventions of recent years have failed to create anything even remotely resembling sustainable economic growth. Central banks were not even able to generate an appreciable amount of CPI “inflation”, despite inflating the money supply at the fastest pace of the entire post WW2 era over the past decade.

As soon as monetary pumping stops or merely slows down, both economic activity and CPI inflation almost immediately sag. Central bankers are united in their response to this failure of their policies: they will simply do more of the same. What would we do without these brilliant central planning bureaucrats?

An Ominous Warning Sign

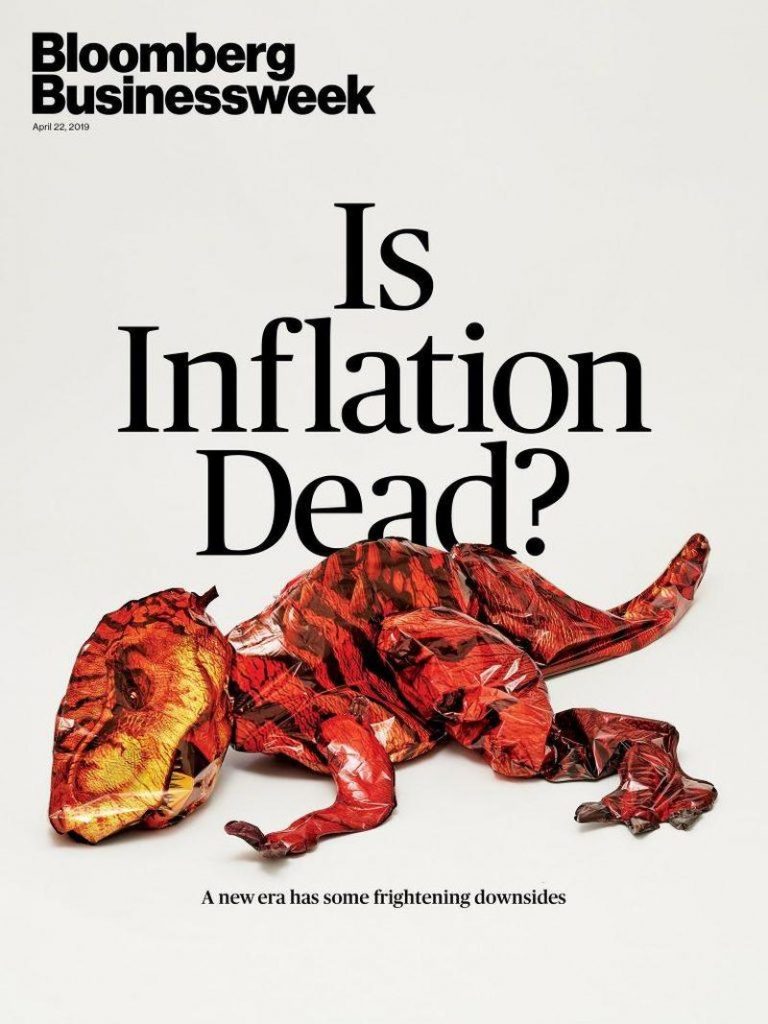

In late 1979, Business Week published a cover story that has become quite famous (presumably to the chagrin of the magazine). It was entitled “The Death of Equities”. Less than three years later, the greatest bull market of all time took off. To be sure, Business Week is far from the only mainstream financial publication publishing cover stories that can serve as a reliable contrary indicator (The Economist is justly famous for doing this as well – recall the 1999 cover “Drowning in Oil”, with WTI crude trading at $10/bbl).

In April of this year, Business Week was considerate enough to provide bond bulls with an early warning shot. It remains to be seen how long the lead time on this one will be; this is to say it is definitely not a useful short term timing tool. But it probably does represent a “heads-up” with respect to the bigger picture:

BW was careful to frame it as a question. Keep in mind that when a headline ends with a question mark, the answer to the question is almost invariably “No”. Oh, and it is a “new era”! We suspect the slain inflation dinosaur will be resurrected at some point.

Let us not forget, central bankers are entertaining the bizarre notion that a minimum of 2% of CPI inflation per year is needed to ensure economic prosperity. This is complete hogwash, to put it mildly – there is neither theoretical nor empirical evidence supporting this idea. Why they have all fallen prey to this obsession is beyond us. We still remember that the German BuBa was proud of having achieved a zero percent inflation rate in the late 1980s. Today this would be considered a “failure” in need of remediation.

The policies central banks pursue to achieve their recently quite elusive goal of 2% CPI inflation are extremely dangerous, since they foster massive bubbles in asset prices as well as capital malinvestment. Moreover, savers and wage earners are robbed by the constant debasement of money and the economy at large is bound to suffer greatly when the enormous credit expansion of recent years reverses.

Negative interest rates ensure capital consumption – as Ludwig von Mises explains in Human Action:

“If the capitalist no longer receives interest, the balance between satisfaction in nearer and remoter periods of the future is disarranged. The fact that a capitalist has maintained his capital at just 100,000 dollars was conditioned by the fact that 100,000 present dollars were equal to 105,000 dollars available twelve months later. These 5,000 dollars were in his eyes sufficient to outweigh the advantages to be expected from an instantaneous consumption of a part of this sum. If interest payments are eliminated, capital consumption ensues.”

“If there were no originary interest, capital goods would not be devoted to immediate consumption and capital would not be consumed. On the contrary, under such an unthinkable and unimaginable state of affairs there would be no consumption at all, but only saving, accumulation of capital, and investment. Not the impossible disappearance of originary interest, but the abolition of payment of interest to the owners of capital would result in capital consumption.”

“The capitalists would consume their capital goods and their capital precisely because there is originary interest and present want-satisfaction is preferred to later satisfaction. Therefore there cannot be any question of abolishing interest by any institutions, laws, and devices of bank manipulation. He who wants to “abolish” interest will have to induce people to value an apple available in a hundred years no less than a present apple. What can be abolished by laws and decrees is merely the right of the capitalists to receive interest. But such laws would bring about capital consumption and would very soon throw mankind back into the original state of natural poverty.”

Mises contends that the so-called natural or originary interest rate – the discount of future goods against present goods (which is incidentally not measurable) – cannot possibly ever be zero or negative. This is conditioned by the passage of time and the finiteness of human life. As Mises puts it, positive time preference “is a category inherent in every human action”.

As long as the terms “sooner” and “later” mean something, the natural interest rate has to be positive. It may well rise to unimaginable heights, for example if we were to learn that the earth was about to be destroyed by an asteroid strike. In that event, there would no longer be a need to provide for the future and the factors of production would become worthless. Everything would be consumed.

In a free market gross market interest rates are conditioned by and adjusting to the natural rate given by society-wide time preferences. In addition, they contain a price premium (or “inflation premium”) and a risk premium. It is of course thinkable that a negative price premium could develop if a sharp rise in the purchasing power of money was widely expected (fat chance!). One should probably also consider the risk of holding cash balances in bank accounts compared to the risk of holding the bonds of a highly rated government borrower. A negative risk premium may develop based on such considerations.

We would argue that a negative price premium doesn’t make much sense in a fiat money system run by central banks that can create money ex nihilo et ad infinitum. A negative risk premium doesn’t make much sense either, considering that almost all of today’s welfare/warfare states are highly indebted (it is generally tacitly acknowledged that their debt will never be paid back).

We concede that holding cash balances in bank accounts may pose a greater risk than holding government bonds, particularly in the event of a systemic crisis – but that does not mean that government debt is “risk free” or deserves to trade at a negative risk premium.

In light of this one must conclude that the main reason for negative market rates is indeed central bank manipulation of interest rates, and/or the expectation that more such manipulation is in store. This has made investing based on the “greater fool theory” a profitable endeavor – for the time being, that is. Buying a negative yielding bond may seem illogical, but it is worth doing it if later buyers are prepared to accept yields that have declined even deeper into negative territory.

Among these future buyers are of course central banks themselves – and since they create money from thin air, they can afford to be “price insensitive”. Ironically, once central banks actually succeed in generating the amount of CPI inflation they are targeting, the prices of today’s negative-yielding bonds will collapse. There will be a lot of wailing and gnashing of teeth when that day comes.

A matrix showing recent yields of various developed country bonds across the entire yield curve.

Negative Yields Carry the Seeds of Their Own Demise

Let us briefly think through the argument Mises makes with respect to capital consumption. Declining interest rates will increase the net present value of capital goods – the more distant to the consumer stage a good is, the greater the effect on its present price will be. In short, the effect of falling interest rates on the prices of capital goods (and titles to capital, such as stocks) is very similar to their effect on bond prices.

This will spur greater investment in long-lasting projects and higher order goods. As long as interest rates are falling on account of a genuine increase in savings, this more future-oriented investment behavior is in line with consumer preferences and therefore bound to increase wealth.

It is different when the decline in interest rates happens due to credit and money supply expansion rather than on the back of a growing savings. Investment in the higher stages of the production structure will still be spurred, but in this case it will be motivated by prices that are actually distorted. It will no longer be in line with actual consumer wants – hence much of it will represent malinvestment.

The more such capital malinvestment occurs, the harsher the eventual recession will be. Zero and/or negative interest rates represent a special situation. As Mises points out, it actually no longer makes sense for capitalists to invest if they are unable to receive a positive return. Note in this context that the spread that capitalists can earn from one stage of the production structure to the next is conditioned by prevailing interest rates (this spread is distinct from entrepreneurial profits – which are fleeting, due to competition).

If we think this through, it implies that production will eventually decrease; at the very least production growth should slow noticeably. At the same time, demand – partly egged on by an expanding money supply – is likely to either remain the same or increase. Eventually, a tipping point is going to be reached. This is when CPI inflation is likely to rise from the dead, so to speak (for a more in-depth discussion of this subject see also “Business Cycles and Inflation” – Part 1 and Part 2).

Keep in mind that the complex latticework of the economy’s capital structure is not a homogeneous self-replicating blob. It requires people to constantly make purposeful decisions on what and how much of it to produce. These decisions will depend on what can be expected to be earned in return for the risk taken. If people increasingly postpone or forego the necessary investment decisions, the future provision of goods will suffer.

Conclusion

Bondholders are facing quite a lot of risk, both in the near term and longer term. It is highly unlikely that price inflation is “dead”, despite the fairly high probability that a short term deflation scare will develop when the bubble in risk assets comes to grief. Since bubble conditions are clearly present in bond markets as well, it is by no means certain that bond prices will streak to even higher levels if e.g. the stock market were to suffer a decline. The recent past is not necessarily always prologue.

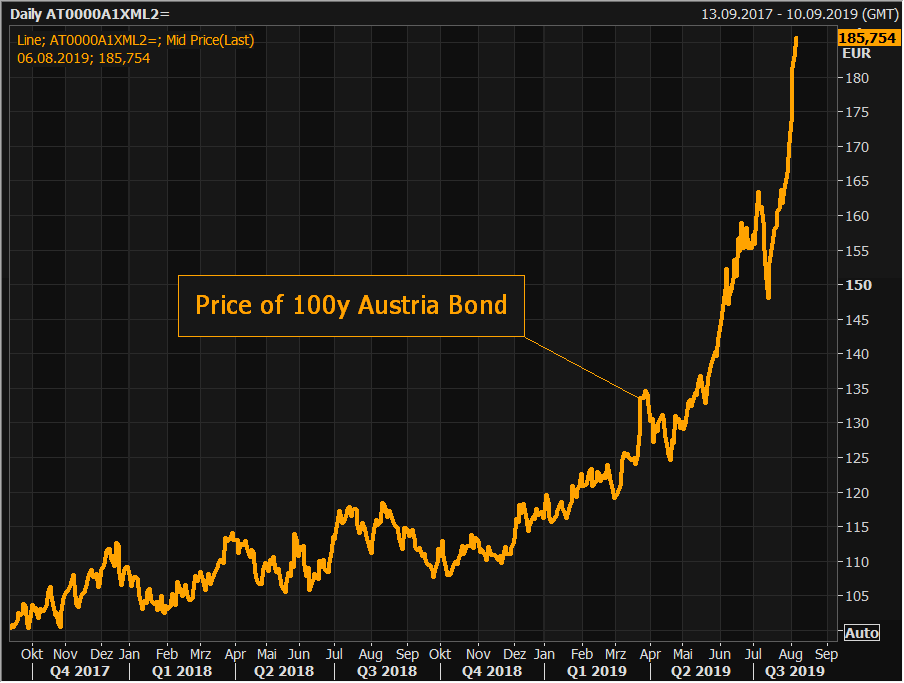

Bonus Chart: Austria’s 100-year Bond

The price of Austria’s 100-year government bond (the government is currently pondering issuing another one as long as demand is strong) illustrates the convexity effect nicely – note how the price curve becomes steeper and steeper. It goes without saying that this is not likely to end well for recent buyers.