Sure Mr. Biden, money is cheap. But who’s money is it?

The White House recently sent a $6-trillion budget plan to Congress.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Biden’s first wide-ranging budget calls for big spending on infrastructure, education and, of course, climate change. His plan lays out $6 trillion in spending against just $4.2 trillion in revenues. That’s an enormous 37% bump up from 2019 spending levels, and it suggests a deficit of $1.8 trillion, nearly double that of 2019.

The idea is to spend now while money is cheap, with interest rates at historical lows. In fact, they’re at the lowest levels in 5,000 years of history.

Bernie Sanders said it was “the most significant agenda for working families in the modern history of our country,” explaining that the budget would reduce poverty through the formation of millions of good-paying jobs.

But deficits pile on to become debt. Repaying that debt becomes a massive burden, so governments use financial repression by keeping interest rates low. That eases the challenge of repayment, but it leads to big inflation.

So the next generation’s best hope is to shield itself with hard assets, with gold chief among them.

A Debt Explosion

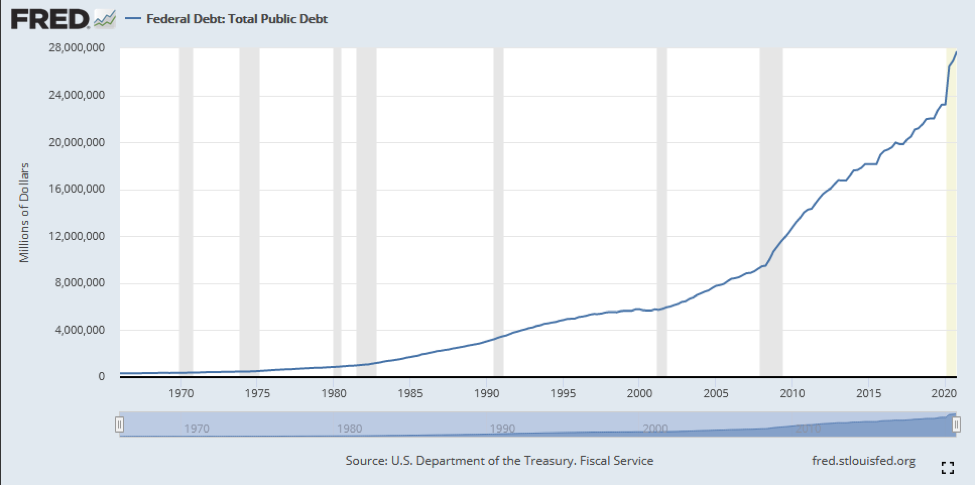

It took the U.S. 211 years, from 1789 to 2000, to rack up $5.7 trillion in debt.

From 2000 it had doubled, within just nine years, to $12 trillion in 2009. Since then, it has more than doubled again, currently weighing in at $28 trillion.

More than half of the entire U.S. public debt, over its 230-year history, has been created in just the last decade.

This chart shows quite clearly that things accelerated in 2000, and then exploded higher with the Global Financial Crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has just added gasoline to that fire.

And now we’re looking to pile on even more.

According to the IMF, at $28 trillion, U.S. debt is about 133% of GDP. Italy is at 157%, Canada is at 116%, France is 115%, the UK at 107%. For comparison, Japan’s debt is near 257% of GDP.

But before you start thinking all is fine because we’re nowhere near Japanese levels, let me throw some cold water on that thought. Consider that a study by the World Bank suggests national debt-to-GDP ratios above 77% for extended periods cause significant slowing in economic growth. In fact, it concludes that each percent above 77% actually costs 1.7% of economic growth.

And for perspective, U.S. debt-to-GDP peaked at 106% after World War II, then dropped consistently to a range of 30%-40% in the 1970s. Levels have risen since then, but the mortgage crisis that became a financial crisis in 2008 pressed down on the accelerator, and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has the pedal pressed firmly against the floor.

Prices Soar

The U.S. Department of Labor reported that the Consumer Price Index climbed 4.2% from April 2020 to April 2021. This means consumer goods prices have jumped the most in any 12-month period since 2008.

Many of the trillions of dollars we’ve added to our collective debts have started floating around. There are few goods and services we can point to that haven’t soared in price.

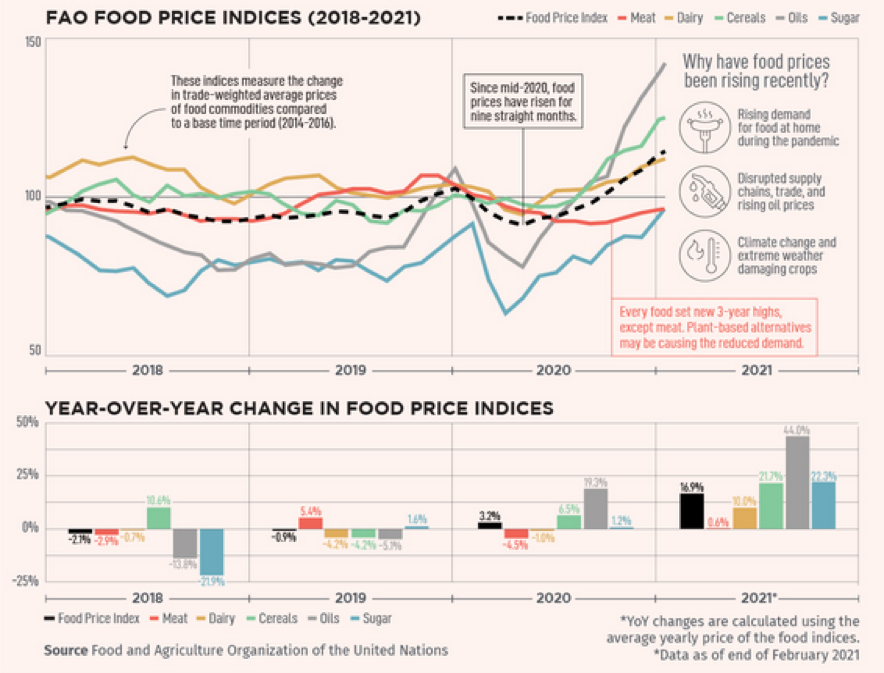

Food is no exception. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) food price index tracks international prices of the most globally traded food commodities. From mid-2020 to end March, (except for meat, so far) food prices had risen for nine straight months. In fact, every food had set new three-year high levels, other than meat, which may be undergoing substitution.

Source: visualcapitalist.com

Of course, even under pandemic restrictions and lockdowns, people still had to eat. So that helps explain support and strength in food prices. But it goes way beyond food.

Major international consumer goods producers Procter & Gamble (NYSE:PG), Kimberly-Clark (NYSE:KMB) and Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO) all recently cautioned they will be raising prices as their raw materials costs have risen.

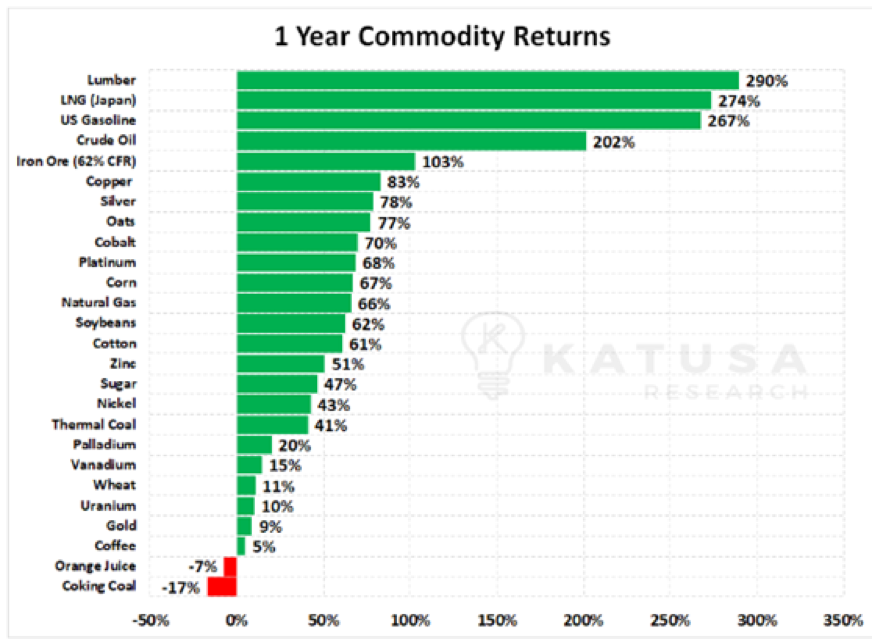

This next chart demonstrates that in spades.

Source: Katusa Research

At Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting earlier last month, Warren Buffet said: “We are seeing very substantial inflation. It’s very interesting. We are raising prices. People are raising prices to us and it’s being accepted.”

“We’ve got nine homebuilders in addition to our manufacture housing and operation, which is the largest in the country. So we really do a lot of housing. The costs are just up, up, up. Steel costs, you know, just every day they’re going up,” he added.

Berkshire also owns Benjamin Moore Paints and Shaw flooring, as well as businesses across multiple industries. If anyone has the pulse on inflation, it’s Buffet.

Money Velocity Kick Starts Inflation

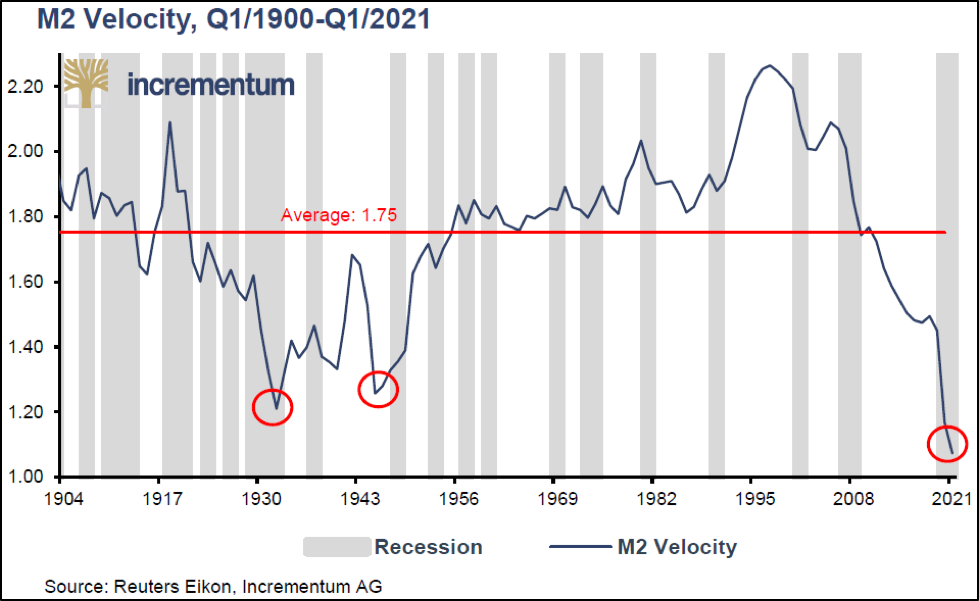

We can also look at this from the perspective of money velocity. The velocity of money is essentially the rate at which a dollar is exchanged in the economy from one entity to another over time. The next chart shows that’s been falling dramatically since the late 1990s. Interestingly, this coincides with the big ramp up in public debt since.

But the Fed just may get the inflation it’s so eager for. And not a moment too soon.

Money velocity could kick into high gear and start ramping up as the pandemic’s limits on activity start to fade. There’s a whole lot of pent-up demand out there with people eager to travel, renovate, go to concerts or sporting events, or just enjoy a restaurant meal.

There is precedent. As stated in the recent annual In Gold We Trust report by Ronald-Peter Stoeferle and Mark J. Valek:

In 1933 and 1946, the velocity of money was similarly low, and in both cases the U.S. government resorted to radical measures. In January 1934, it devalued the U.S. dollar against gold by almost 70%, and in the period 1946–1951 it enforced financial repression in cooperation with the Federal Reserve, which capped interest rates at a low level. Both times, this massive intervention resulted in significantly higher inflation rates in the years that followed. Currently, the velocity of money is at even lower levels than in 1933 or 1946. We expect history to repeat itself and central banks to seek their salvation in financial repression.

Piling on record historical global debts and holding rates down at 5,000-year lows is likely to stoke inflation like we haven’t seen for a long time.

Gold has been sensing this since 2000, but has kicked into high gear once again since late 2019. You’ve no doubt seen and felt increases in food and pretty much everything else. The Fed says the recent bump in inflation is transitory, but the action in precious metals says otherwise. It’s why gold prices are up 42% in just the last two years.

Sustained high inflation, coupled with low nominal interest rates, creates an environment of extended negative real interest rates. And that’s when gold thrives. At $1,900, gold is still 9% below its all-time high. But adjusted for inflation, gold is still 26% below its 1980 all-time high.

With money so cheap, record global debt will keep expanding as governments keep spending money it doesn’t have. That coupled with historically low interest rates and a likely resurgence of money velocity means inflation will rear its ugly head.

It’s time to fight back. Own gold.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.