It was only a few days ago when the stock market celebrated a Trump-Xi tariff delay. And it was only a few days before that when Federal Reserve Chairman Powell flip-flopped on the extent of rate hiking yet to come.

Both of the above-mentioned actualities sent stocks and risk assets soaring higher. And both were expected to serve as tailwinds for a phenomenal December rally.

So how did the Dow lose nearly 1600 points in two days, then recover roughly 700 of them on news of a rate-hike pause? Trouble with the curve.

Indeed, the month began with a recessionary warning. On Monday, when the yield on 5-Year Treasuries fell below the the yield of 3-Year Treasuries, the inversion signified a safety-seeking desire for longer-term maturities.

Granted, the fact that 3s and 5s have inverted is not particularly telling in and of itself. The big time curve inversion that analysts and economists look for is when the 10-Year note yields less than the 2-Year note. Every recession since World War II came after 2s and 10s inverted.

Nevertheless, buyers had already been pulled into equities earlier, alongside a more subdued Fed as well as the perceived easing of trade tensions. When algorithmic trading picked up on a “first-time-since-2007 event,” sell orders began accumulating and, eventually, overwhelmed a lack of additional buying interest.

There’s more.

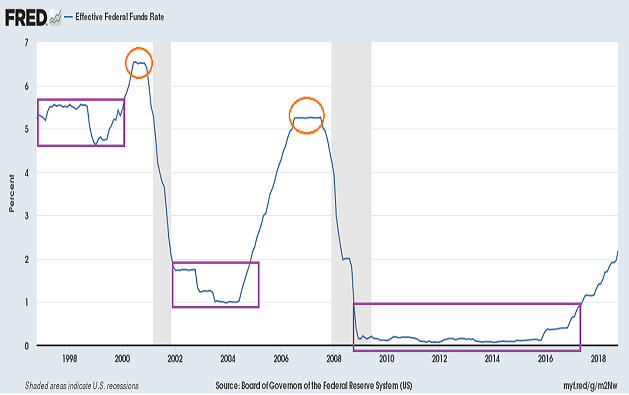

Participants in the financial markets, including “the computers,” eventually factor in the probable implications of a Fed that stops raising rates. Specifically, a neutral plateau may precede a recession. (See the orange circles below.)

“There’s no recession in sight,” you argue. In particular, employment indications remain robust.

On the other hand, we are only a few months away from a tenth year of economic expansion. The longest growth periods in U.S. history — 1960s and 1990s — did not journey into an eleventh year. It follows that probability alone implies we are closer to the finale than to a second act.

Even before the recent rout, defensive stocks began outperforming high beta stocks. Consider the sentiment shift since October. Former leadership via SPDR Select Sector Technology (XLK) and SPDR Select Sector Consumer Discretionary (XLY) have been no match for the perceived safety of SPDR Select Sector Health Care (XLV) and SPDR Select Sector Consumer Staples (XLP).

Surely, members of the Federal Reserve must know what they are doing. After all, isn’t the central bank of the United States comprised of the smartest men and women in the country? The world?

Intelligence notwithstanding, members of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) have not been particularly successful at identifying the development of recessionary pressures. Alan Greenspan hiked the Fed Funds Rate aggressively in 1999 and 2000, only to discover that the Fed’s rate-related popping of the Nasdaq bubble led to massive layoffs in the dot-com economy. Recession followed.

More recently, on January 10, 2008, Ben Bernanke infamously stated, ““The Federal Reserve is not currently forecasting a recession.” Unbeknownst to the Bernanke-led Fed, the Great Recession had already started in December of 2007.

There are some fairly straightforward markers for recession forecasting. I shared my predictive model in December of 2007 with readers on platforms like Seeking Alpha, theStreet.com and ETF Trends. At that time, I placed recession probability at 70%. (Note: Investor’s Business Daily interviewed me in the first week of January of 2008; my model raised the probability to 80%.)

Leaders at the Federal Reserve are certainly smarter than I am. Indeed, they knew just how powerful it would be to give word to the Wall Street Journal of a potential rate pause going forward today, when there was a mere 30 minutes to go in the trading session. Doing so put a band-aid on a particularly painful two-day sell-off.

Still, it is important for near-retirees and retirees to understand that the Fed may not be able to preserve account values through jawboning alone. Even if Chairman Powell tells the world on December 18 that the global economy is moderating, and that the Fed will be pausing on rate hike endeavors moving ahead in 2019, the dovish guidance may merely delay a more serious reckoning.

Fed Chairman Powell’s job may be the most difficult on the planet. Increasing borrowing costs for corporations, consumers and government? It may have been a whole lot easier to keep on suppressing borrowing costs like Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen before him.

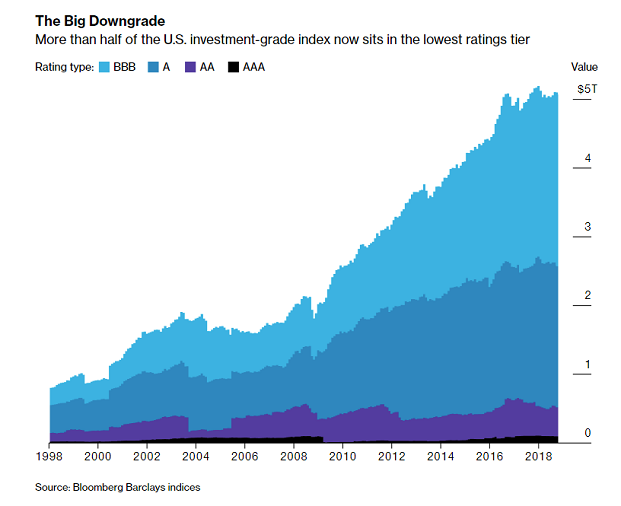

Most notably, Powell and his colleagues have acknowledged the risks of excess leverage in the corporate bond space. In a recent Fed report, they wrote,

“The distribution of ratings among investment-grade corporate bonds has deteriorated. The share of bonds rated at the lowest investment-grade level (for example, an S&P rating of triple-B) has reached near-record levels. As of the second quarter of 2018, around 35 percent of all corporate bonds outstanding were at the lowest end of the investment-grade segment, amounting to about $2¼ trillion.”

“In an economic downturn, widespread downgrades of these bonds to speculative-grade ratings [to junk] could induce some investors to sell them rapidly, because, for example, they face restrictions on holding bonds with ratings below investment grade. Such sales could increase the liquidity and price pressures in this segment of the corporate bond market.”

Why is this acknowledgement significant? For one thing, it highlights the reality of what is likely to happen when the Fed manipulates rates way too low for way too long. In the previous expansion, scores of consumers took on debts that proved unsustainable. In this go around, many companies (and government) have been the ones to borrow excessively.

Acknowledging the debt concerns is meaningful for another reason. Subprime debt completely seized up in 2008, where a debt crisis exacerbated the recession.

Can Powell continue raising the shortest term rates as well as reducing bonds on the Fed balance sheet without eventually sparking a similar crisis? As marginal investment grade debt morphs into junk? Will a pause in 2019 merely serve as a prelude to an inevitable downturn in stocks and corporate bonds, as well as economic contraction?

In spite of the risks to financial assets, Chairman Powell has yet to throw in the towel completely. Current market volatility may be enough to inspire the communication of data-dependent pausing, but it is unlikely to bring a shift form tightening to direct easing.

A pause and/or a sharp slowdown in rate hike activity is likely to become a neutral plateau. During the neutral rate policy phase (See the orange circles above), stocks may not fully capitulate on the downside. In the same vein, riskier assets may struggle to recapture previous glory in the presence of a wishy-washy Fed.

Until Powell throws in the towel in a decisive manner, with the promise of more stimulus — zero-rate policy, negative rate policy, quantitative easing — riskier assets will trade like riskier assets. And that may require “dry powder” cash for an opportunity to take on more S&P 500 exposure at a 25%, 35% or 45% bearish discount.

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (“blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.