Writing for the Upshot section of the New York Times, Harvard economist Greg Mankiwhas weighed in on the Pikkety debate. He accepts Pikkety’s scenario of ever increasing inequality as at least a “provocative speculation,” if not established fact, but then asks, So what? What is wrong with inequality and inherited wealth?

Nothing, says Mankiw. In fact, he maintains that if we consider not only the direct effects on the family but also the indirect effects on the broader economy, inherited wealth is good not just for the rich but for the rest of us as well:

When a family saves for future generations, it provides resources to finance capital investments, like the start-up of new businesses and the expansion of old ones. Greater capital, in turn, affects the earnings of both existing capital and workers.

Because capital is subject to diminishing returns, an increase in its supply causes each unit of capital to earn less. And because increased capital raises labor productivity, workers enjoy higher wages. In other words, by saving rather than spending, those who leave an estate to their heirs induce an unintended redistribution of income from other owners of capital toward workers.

This may be good textbook economics, but it should not be allowed to pass without three major caveats.

The link between productivity and wages is broken

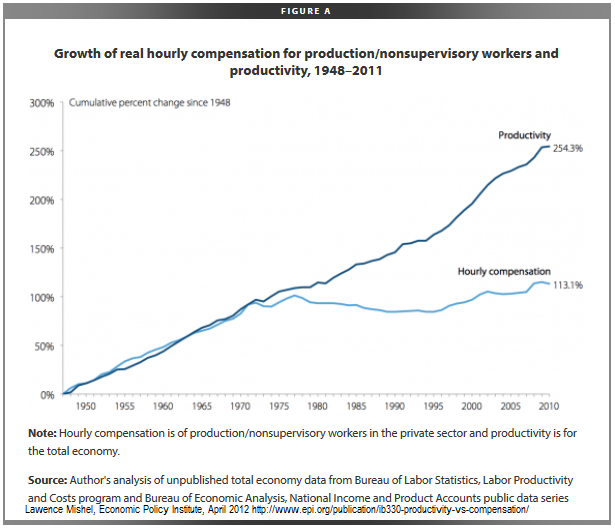

Yes, in the textbook model of labor markets, higher productivity, other things being equal, leads to higher wages, but in recent decades, other things no longer seem to be equal. The once-tight link between higher productivity and higher wages seems to be broken. As shown by the following chart, drawn from a study by Lawrence Mishelfor the Economic Policy Institute, the disconnect began long before the Great Recession. Wages did track productivity closely up to 1970, but they have stagnated since then even though productivity has continued to grow.

As Mishel points out, much of the growing gap between productivity and hourly compensation of nonsupervisory workers is explained by the growing share of capital income in total income. His data show that the share of capital income (interest, dividends, profits, rent and so on) is now at its highest level in 70 years. It is not exactly clear why this is happening—various writers point to globalization, the decline of labor unions, technological change, the falling real value of the minimum wage, the rise of hedge funds and other financial innovations, and other factors. Whatever the cause, the result is the opposite of what we would expect from Mankiw’s “other things being equal” argument, which is that higher saving plus diminishing returns to capital should lower capital’s share of total income.

Slack in the economy

The second caveat is that Mankiw’s argument is fully valid only for an economy at full employment. If the economy is in a slump (if I may bring in some more textbook economics) an increase in the average saving rate will lower total spending and the slump will worsen. The U.S. economy has been weak for several years now. Given that the rich save a higher share of their income than the poor, it is plausible that increasing inequality of income is prolonging the slow recovery, not hastening its end.

Economists usually discuss policies regarding income distribution and those regarding the business cycle separately, but we might speculate about how to combine the two. For example, we might impose an income tax surcharge on high incomes, including investment income, that varied directly with the output gap—high taxes in a slump, lower taxes in a boom.

Taken in isolation, such a policy would be procyclical, but it could be made countercyclical by requiring that the proceeds of the surcharge go directly to fund infrastructure investment. The math is pretty simple: Assume that the marginal propensity to save is, say, 40 percent for high earners. If so, for every $100 million in extra taxes collected during a slump, you would lose $60 million in spending on yachts and premium bourbon but gain $100 million of spending on roads and bridges. The result would provide a net economic stimulus. During a boom, the signs would reverse, reducing the danger of overheating the economy.

I’m only half-serious about this. Tax and spending lags would reduce the effectiveness of the policy, and it would admittedly make tax planning difficult for the high earners. Still, you can see the point—more income inequality is not automatically “good for the economy” when you take cyclical factors into account.

What policies are we comparing?

Third, according to Mankiw, when we consider matters from a policy perspective, we need to consider the indirect effects of inequality on the broader economy. Yes, but we need to ask, consider them in comparison to what?

Mankiw argues that saving helps the economy by encouraging investment, which raises productivity, and in turn, raises wages. We have already seen that the link between rising productivity and rising wages is weak, but for the sake of discussion, let’s stipulate that it is strong. Let’s also assume constant full employment, so that we don’t have to worry about excess saving or insufficient aggregate demand. That leaves us with the proposition that more saving is good—but is greater income inequality the best way to encourage saving?

Putting the question that way raises two problems. First, if the answer were yes, then what would be the optimal degree of inequality? The degree that maximizes saving might be even greater than we have now. The degree that maximizes wages might be lower. Even if inequality were the only factor affecting saving, it is not obvious the recent increases in inequality have moved us closer to, rather than farther from, the optimum.

More importantly, there are other ways to promote saving that would, arguably, be more effective in achieving higher productivity, wages, and growth. For example, reformers have suggested switching from income taxes to consumption taxes as a way to encourage saving. Alternatively, we could encourage saving by reforming our retirement system. I looked at some ways to do so in a post last year. One approach, proposed by William Galeof the Tax Policy Center, would be to replace the current tax deductibility of contributions to retirement plans with a refundable tax credit that would be deposited directly in an individual’s retirement account. Another idea would be for the Treasury to issue special “R-bonds” that would carry a guaranteed positive real interest rate if deposited in a qualifying retirement account.

The above proposals focus on personal saving. Instead, we might try to encourage business saving through appropriate reforms to the corporate income tax, including measures to encourage the repatriation of existing corporate savings so that they could be invested at home. We could also reform fiscal policy in ways that encouraged greater government saving and investment.

Any of these policies could, in principle, give us as much saving as we have with less inequality, or more saving with the inequality we have now. Raising inequality is not a necessary condition for more saving.

The bottom line

Mankiw wants us to regard income inequality and inherited wealth with gratitude:

Rising income inequality over the past several decades has meant meager growth in living standards for those near the bottom of the economic ladder, and one might worry that inherited wealth makes things worse. Yet standard economic analysis suggests otherwise. . .

Those who have earned extraordinary incomes naturally want to share their good fortune with their descendants. Those of us not lucky enough to be born into one of these families benefit as well, as their accumulation of capital raises our productivity, wages and living standards.

I can’t agree. Even if inequality promotes saving, as he claims, the link between higher saving by the rich and higher living standards for average Americans is far more tenuous than he suggests. Furthermore, even if increased saving is an appropriate goal, raising income inequality seems a clumsy way of getting there.

By all means, let the rich save as much as they want and share their wealth with their descendants if they choose. But please, don’t try to pass off inequality as good public policy.

Writing for the Upshot section of the New York Times, Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has weighed in on the Pikkety debate. He accepts Pikkety’s scenario of ever increasing inequality as at least a “provocative speculation,” if not established fact, but then asks, So what? What is wrong with inequality and inherited wealth?

Nothing, says Mankiw. In fact, he maintains that if we consider not only the direct effects on the family but also the indirect effects on the broader economy, inherited wealth is good not just for the rich but for the rest of us as well:

When a family saves for future generations, it provides resources to finance capital investments, like the start-up of new businesses and the expansion of old ones. Greater capital, in turn, affects the earnings of both existing capital and workers.

Because capital is subject to diminishing returns, an increase in its supply causes each unit of capital to earn less. And because increased capital raises labor productivity, workers enjoy higher wages. In other words, by saving rather than spending, those who leave an estate to their heirs induce an unintended redistribution of income from other owners of capital toward workers.

This may be good textbook economics, but it should not be allowed to pass without three major caveats.

The link between productivity and wages is broken

Yes, in the textbook model of labor markets, higher productivity, other things being equal, leads to higher wages, but in recent decades, other things no longer seem to be equal. The once-tight link between higher productivity and higher wages seems to be broken. As shown by the following chart, drawn from a study by Lawrence Mishel for the Economic Policy Institute, the disconnect began long before the Great Recession. Wages did track productivity closely up to 1970, but they have stagnated since then even though productivity has continued to grow.

- See more at: http://www.economonitor.com/dolanecon/2014/06/23/does-inherited-wealth-really-help-the-economy-a-reply-to-greg-mankiw/?utm_source=feedly&utm_reader=feedly&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=does-inherited-wealth-really-help-the-economy-a-reply-to-greg-mankiw#sthash.jMa5nxlg.dpuf