- All Instrument Types

- Indices

- Equities

- ETFs

- Funds

- Commodities

- Currencies

- Crypto

- Bonds

- Certificates

Please try another search

Bonds

What Is A Bond?

A bond is a debt instrument that's created by a borrower for a specific amount of capital to be loaned over a specific period of time.

How Do Bonds Work?

The purchaser of the bond is the lender or bondholder. The lender receives interest payments from the borrower on specific dates until the bond matures, at which point the borrower returns the original amount of the bond back to the lender.

Governments, agencies, municipalities and corporations/companies issue bonds as a way of raising funds for such things as buying equipment, new projects, or refinancing existing debt. Issuing bonds can be more attractive than getting a loan from a bank because the bond is created by the borrower, whereas bank loan costs and terms are often more expensive and restrictive.

The specific amount of capital borrowed is called the face value; the specific period or duration is known as the maturity. The regular payments made by the borrower often occur annually or semi-annually, and the amount of each payment is determined by the bond’s annual coupon rate--expressed as a percentage of the face value.

For example, if company XYZ sells a bond with a face value of $1000, maturity of 3 years, a coupon rate of 5%, and semi-annual coupon dates, it would pay the bondholder (investor) $25 every 6 months for three years. The return, generally referred to as the yield, on the investment would be 5% annually and at the end of three years, XYZ company would return $1000 to the investor.

A bond’s coupon rate is largely determined by the risk of default by the borrower, but also by the duration of the bond, e.g., the longer the maturity of the bond the greater the chances that a borrower’s situation could change, making it more possible they could have trouble repaying the bond.

Bond Valuations

After being issued by a borrower, a bond can be traded in the same way as any other security. The value of this particular asset is in the fixed stream of payments.

On the secondary market, investors are willing to pay more or less for a bond depending on the interest rate environment at the time of the sale. The sale price changes the yield of the bond; the more paid for a bond with a fixed coupon rate the lower the yield. Conversely, the less paid, the higher the yield.

For example, using the XYZ bond mentioned above, consider what would happen if the original owner decides to sell the bond when interest rates of bonds with similar risk and duration have risen one percentage point.

In that case, the price to purchase the XYZ bond would fall, and the yield would rise because other bonds with better rates are now available. Conversely, if interest rates fell one percentage point, the XYZ bond would become more valuable, and the yield would fall, because it now has a better rate than other available bonds.

What are Government Bonds?

US Treasurys are called bonds if the maturity is longer than 10 years, notes if the maturity is between one and 10 years, and bills if less than one year.

Municipal bonds, often called munis, have tax free benefits. They are issued by states, cities, counties and other, smaller government entities in order to fund local infrastructure or educational projects, for example.

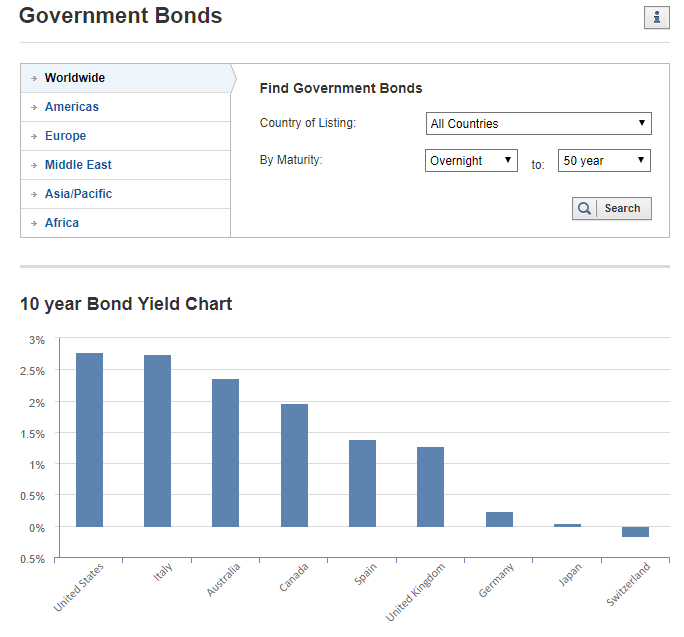

The Government Bonds page at Investing.com provides a searchable database of sovereign bond rates available around the world. The page begins with a chart of 10-year bond yields, often described as the benchmark rate, of major countries.

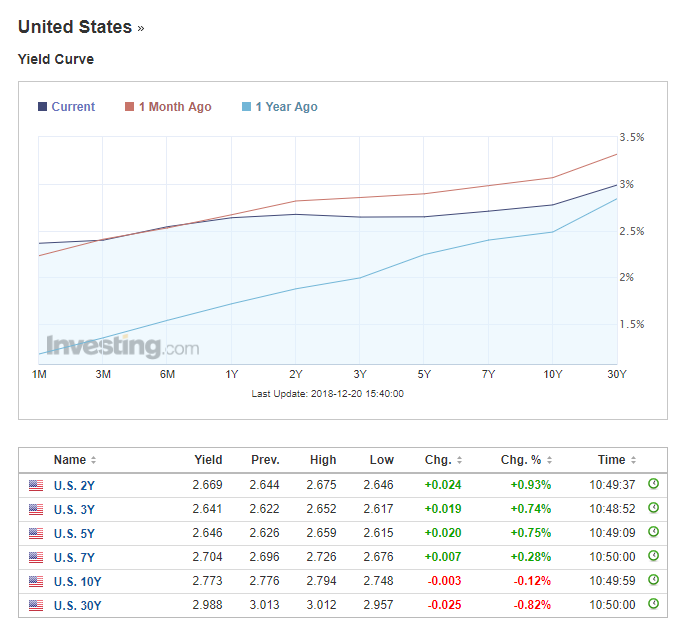

Searching the database by country and bond maturity produces a chart with current and historical yield curve data for each selected maturity. Tables of major bonds of different maturities follow, along with indices and prices of financial futures. The last table on the page details upcoming auctions around the world. For example, US Bonds:

Navigating across the entire section via the bonds tab allows users to filter for countries, spreads as well as major bond-related indices.

What Are Bond Investment Variations?

Bonds can be “callable," meaning the borrower chooses to pay off the loan early. In such cases, the bond issuer returns the original amount of the bond back to the bondholder (aka investor) and stops making the interest payments. Munis and corporate bonds are callable. Treasuries are not (save for very rare cases).

A bond can also be "putable" if it has that option stipulated at the outset. A putable bond allows the bondholder the right to exit the transaction before maturity if they so desire. However, this choice can only be exercised if certain pre-stipulated events or conditions occur.

Bonds can also be “zero-coupon,” meaning no interest (coupon) is paid to the bondholder while they hold the bond. Zero-coupon bonds are generally issued at a deep discount versus its face (par) value. When this type of bond matures, the holder is repaid at par rather than at the discounted rate, which is how the investor earns their return.

Corporate bonds can also be “convertible,” which allows bondholders to convert the bond to shares of the company’s stock under certain conditions.