There are two eminently reasonable ways to stop the off-kilter spinning top that Wall Street has become:

1. Starve the Beast

2. Allow only human beings to trade.

OK, I realize the genie is out of the bottle, so the second option is simply not going to happen. The regulators are in bed with Wall Street's trading desks so this eminently reasonable solution is off the table. That leaves #1.

Market volatility has increased due to institutional day trading, program trading, high frequency trading, and trading for the sake of trading. Partly as a result of this hijacking of "investing," individual investors have increasingly eschewed the equity markets in favor of bonds, CDs, gold coins and other non-equity investments.

But before we rush to blame bank and Wall Street trading desks for our woes (though they are due their fair share of shame and blame) let's take a look at what we ourselves have done, often with the best of intentions, that has changed this dynamic. Not that long ago, markets were dominated by individual investors. Those markets were considerably less volatile, and instead were characterized by positions held for long term future growth. Today, the bulk of transactions are institutional (trading desks, pension funds, hedge funds, mutual funds, ETFs, and the like) which are explosive in nature and, for the most part, incredibly short-term -- close of business today is a good time to flatten all positions

Looking back just to the late 1960s, only 23% of total buy and sell transactions were conducted by institutions. There were two primary reasons for this. First, almost everyone working for a big company had a pension, so the big institutions of the day were the pension funds. They invested the bulk of their funds in debt instruments, rather than equity. It wasn't as exciting but in that more restrictive regulatory time, they had to follow the Prudent Man rules, so they never forgot that the return of capital was the first order of business, not the return on capital.

The other reality then was that individuals took responsibility for their own investments. With no control over the pension monies, they invested their discretionary income in equities and the relative handful of mutual funds.

The situation today is completely reversed. Institutions account for somewhere between 75 and 80% of all trading in any given year; call it 77%. That would mean a complete and total reversal of the markets known to previous generations of investors. Individuals now contribute just 23% of total transactions. As if that isn't bad enough, it gets worse.

Since dark pools and off-exchange trading are murky at best, we must rely on estimates for the percent of total volume conducted by algorithmic trading without human intervention after the parameters for the trade have been established. Many analysts believe they account for as much as 70% of each day's total volume. If that's so, it means that institutional traders acting on their experience and reason account for 7%, individuals for 23% and the rest is done based upon models designed some time between last year and this morning.

Is it any wonder that we have flash crashes? If up to 70% of the average daily volume is done without human intervention, that's a billion shares or more of potential volatility. Not all these algorithms are designed for scalping, of course; some are hedges against real portfolios, triggered when a mutual fund needs to raise cash for redemptions, sold versus trailing stops as a result of good price appreciation, etc. But let's be honest. Most of these algorithms are designed to scalp pennies in seconds (or mills in nano-seconds.) When enough of these automatic trades are triggered by the same event, we see extreme volatility - nearly 20,000 such events in the last 6 years alone, with the Flash Crash of May 2010 being the most public, if not the most egregious, example.

Earlier I said we have mostly ourselves to blame. How did we get in this predicament? There are many answers, but three that you, I and every other individual investor must accept responsibility for, include:

(1) The rise of corporate 401(k)s without, in most cases, any Prudent Man restrictions. This is like setting a kid free in a candy store with no guidance whatsoever on what is healthy and what is not.

(2) The false promise of indexing, which demeans every investor's intellect by presuming all of us who don't work for a bankster are too dull-witted to beat the market, if by no other means than taking some money off the table when it is appropriate to do so. "Don't trade!" Wall Street intones. "You never know when you might miss something." My response? That cuts both ways; I'd just as soon miss the occasional calamity, thank you. And if I miss something good, stocks are like streetcars - wait 10 minutes and another one will come along.

(3) The exponential growth of hedge funds To justify their ridiculous "20 and 2" pricing (2% management fee plus 20% of any profits they make) they don't invest in an index fund or even, in many cases, "invest," as in buying and holding quality companies, at all. There are a few hedgies that carry on in the tradition of Ben Graham and Warren Buffett, both of whom ran hedge funds (but not at 20 and 2!) But most hire 20-something hackers whom they expect to write brilliant quant algorithms for the black box.

The charts that follow are merely snapshots in time and cannot reflect every external factor that may have influenced volatility. Nor are they a complete picture of any one year or decade. Instead, I selected the first 7 months of this year, just past, and compared them to the same 7 months in each year ending in "2" since 1972. As you will see, 1972 was a most appropriate starting point to study volatility in light of the three changes with 401(k)s, indexing, and hedge funds.

If you believe, as I do, that there is a certain seasonal, cyclical and secular rhythm to the markets, selecting 5 "snapshots" may be quite telling.

1972 was pre-401(k), pre-index fund and pre-proliferation of hedge funds. The S&P traded between 102 and 108 during the first 7 months of 1972. Sounds boring, but that lack of volatility might be a welcome interregnum today.

However - the next year, in 1973, Professor Burton Malkiel wrote A Random Walk Down Wall Street, propounding the efficient market hypothesis, positing that prices of publicly traded assets reflect all publicly available information. I think that's hogwash and apparently Warren Buffett, John Templeton, Peter Lynch and a whole host of non-academics agree, but we must concede this book was a watershed event.

Among Malkiel's prescriptions:

What we need is a no-load, minimum management-fee mutual fund that simply buys the hundreds of stocks making up the broad stock-market averages and does no trading from security to security in an attempt to catch the winners.

It seems John Bogle was all ears. The next year he founded The Vanguard Group to do just that and in 1975 started the fund that would become the biggest in the world, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund.

Another event was taking shape during this decade, as well. In 1978, Congress amended the a portion of the Internal Revenue Code, later called section 401(k). The law went into effect on January 1, 1980.

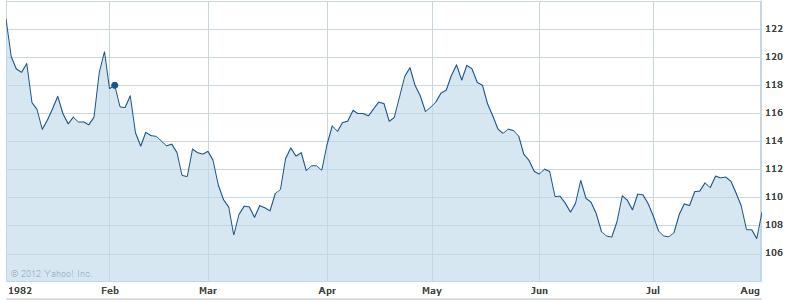

In the first 7 months of 1982, the market swung a little over 12%. Index funds and 401(k)s were still new ideas.

By 1984, however, 17,303 companies were offering 401(k) plans in lieu of pensions and we -- you and me -- were not just letting fixed income and blue chips fulfill our pension needs. We wanted action which meant a proliferation of mutual funds offered with no loads or other fees. Suddenly we wanted to see a little volatility, because that meant more profits, right? By 1992 it was "let the good times roll."

Unlike the two previous 7-month snapshots, one of which went slowly up, the other slowly down, this particular period of 1992 ended roughly where it began - but the volatility had increased markedly. Note, for instance, that the 1972 chart looks like a series of rolling foothills. Contrast that with 1992, where it more resembles a series of jagged peaks and troughs.

The result was that we had a bit of a comeuppance in 2002. We had given many of our investable dollars to mutual funds via 401(k)s -- and demanded that they outperform their peers. Here were the fruits of those decisions: in the bear period these 7 months covered in 2002, the S&P had a swing of 44% peak to trough -- in 7 months. This would have been the return in those index funds that Wall Street so wants you to buy and hold. Of course they do! If you take your money off the table, they don't have anything to play with. The "institutional" money isn't money they have laying around for a rainy day - it's your money. If you don't give it to them, the Beast starves.

Worse, those who selected the go-go choices for their 401(k)s (and other investable funds,) lost even more. Double-worse, we had deluded ourselves into believing during the dot.com.bomb that tech was the be-all and end-all to investing so we lined up around the block to give our money to hedge funds. Each touting their boy-wonders as the ones who could turn a sow's ear into a silk purse.

Who invested in these hedge funds? Typically, other institutions, like your pension fund or university endowment. Hedge funds are far less regulated because they are sold only to accredited investors and institutions.

Remember those pension funds that used to invest in bonds? Not no more. Having lost so much in the dot-com-bom, many of them were now giving chunks to hedge funds, trying desperately to make it all back to save their jobs.

This brings us to the current period, of which we are all personally and, for some people, painfully aware. The S&P 500 shot from 1280 to 1420 in the first 120 days of the year, then plunged right back down to 1280 in the next 60. We've now seen it roar back above 1400, so now -- where?

Everyone will have their own opinion, but I have chosen to position our clients in such a way that they are hedged with an ever-so-slight downward bias. I do so with equities, highly liquid ETFs which I can sell any time, and even with a few specialty mutual funds like the best of the long/short funds. My concern is that this market looks suspiciously like a triple top and, worse, is occurring at a time of maximum complacency among the investing public. Whistling past the graveyard is no way to protect yourself from the grave robbers at Wall and Broad.

Since we brought it on ourselves, we can, at least partially, fix it ourselves. Of course we could petition the regulators, for all the good that will do. (I hear Jim Morrison in the background singing "Petition? Petition? Petition the Lord with prayer?") And we could vote into national leadership office men and women who share our concerns and hope they have a real life to return to so they aren't easily co-opted by all that free Wall Street money to get them re-elected over and over again ad infinitum, ad nauseam.

Perhaps more realistically, and certainly within our immediate power to control: First, realize that your 401(k) is neither a particularly good investment vehicle nor a plaything. We have had clients come to us who still had money in the 401(k) of a company they left ten years ago and military members who still have the Thrift Savings Plan 10 years after they retired, instead of rolling it to a self-directed IRA. Why would they consider letting some pension fund give money to a hedge fund to speculate with their money? That laziness translates to more money for the big institutions to wreck the markets with their short-term trading, high frequency trading, quarterly window dressing, etc.

Starve the Beast. The "institutional money" isn't theirs -- it's ours. Don't give it to them via 401(k)s when you could roll it into your own IRA. Don't just toss it into an index fund that mirrors the biggest companies with the most liquidity that institutions view as their personal playground. Use them when diversification is more important than performance. And, finally, query your plan administrators -- how much business are they giving to hedge funds without you having a say in the strategies employed? Or your mutual fund managers - does their charter allow them to play in the derivatives market or give money to sub-advisors which are nothing more than hedge funds?

Take responsibility for your own investing. Among the many companies I believe have fallen, even in this "good" market, to prices that make them worthy of purchasing for greater gains in the coming months and years are: ABB (ABB), Total Petroleum (TOT), Pepsico (PEP), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), Statoil (STO), Joy Global (JOY), Natural Resource Partners (NRP), Bank of Montreal (BMO), Imperial Oil of Canada (IMO), Plum Creek Timber (PCL), Siemens AG (SI), Weyerhaeuser (WY), Penn Virginia (PVR), ScotiaBank (BNS), and Cenovus (CVE.)

I believe selecting great companies at a good price will provide far greater reward than playing Wall Street's silly in-and-out trading games or trusting our future to an index fund. These firms and others like them are a fine place to begin your own due diligence.

The markets are volatile because we outsourced our responsibility for our own future. Take it back. The decline in volatility will make the markets worthy of our research, attention and success once again.

Disclosure: We remain hedged in this volatile market. We own inverse ETFs that balance our long equities, including some of those above, leaving us with the nice dividends from the long side. We also have begun writing puts against some fine companies we'd like to own, especially at lower prices.

The Fine Print: As Registered Investment Advisors, we see it as our responsibility to advise the following: we do not know your personal financial situation, so the information contained in this communiqué represents the opinions of the staff of Stanford Wealth Management, and should not be construed as personalized investment advice.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results, rather an obvious statement but clearly too often unheeded judging by the number of investors who buy the current #1 mutual fund only to watch it plummet next month.

We encourage you to do your own research on individual issues we recommend for your analysis to see if they might be of value in your own investing. We take our responsibility to proffer intelligent commentary seriously, but it should not be assumed that investing in any securities we are investing in will always be profitable. We do our best to get it right, and we "eat our own cooking," but we could be wrong, hence our full disclosure as to whether we own or are buying the investments we write about.

Disclosure: I am long NRP, PVR, STO, TOT, PEP, JNJ, PCL

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Time For Investors To Take Back Wall Street. Here's How

Published 08/16/2012, 01:36 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Time For Investors To Take Back Wall Street. Here's How

3rd party Ad. Not an offer or recommendation by Investing.com. See disclosure here or

remove ads

.

Latest comments

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2024 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.