A Multi-Asset Approach to Capitalize on Rising Uncertainty: Buy Volatility

Today's markets have become divorced from economic reality, thanks largely central bankers too scared to address growth challenges. Instead, they implement programs under which synthetically low interest rates and an endless credit convalescence is the new norm. This only leads to artificially inflated credit and equity markets, capex atrophy and an institutionalized misallocation of capital.

In the U.S., Washington is unable to make critical structural changes, as it stands gridlocked while our nation’s biggest economic competitors – China, Russia, and the oil-producing nations of the Middle East – are doing everything possible to end U.S. monetary hegemony. Risks has surpassed levels ever seen in history, yet markets have hardly made any real adjustment.

While the global marketplace confronts a minefield of risks, one of the most threatening is that of over-leverage.

Over-leverage and insolvency issues do not create themselves. Over the last decade, and more so in the recent 6-7 years, the free money era has prevailed among global central banks. It first began with the Fed’s implementation of massive quantitative easing, allowing newly created dollars to roll off the Greenspan/Bernanke printing press for years on end.

As the dollar became increasingly cheap, emerging market governments (and companies) took advantage of the opportunity to borrow on the cheap (in cheap USD), but forces are now moving in the opposite direction. As the Fed looks to reverse its hyper-accommodative monetary policy, the dollar is strengthening while many emerging market currencies are being devalued.

To make matters worse, these countries often produce largely commoditized products heavily reliant on demand from China, which is growing much more slowly than anticipated. As the impacts of both weak currency values (and thus a weak relative value of sales and earnings against debt service requirements) and declining demand for their product pressure these emerging markets from all angles, they’re approaching default on dollar-denominated debt obligations (if they haven’t gone into default already). Further strengthening in the dollar could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back, ultimately leading to the unraveling of domestic and international credit markets, which would inevitably leave wreckage in the equity markets as well.

A similar dynamic, that of overleverage, has taken place in the domestic consumer and small-to-medium-sized business (SMBs) lending markets, as institutional investors with masses of cash fight for qualified borrowers after the Fed flooded the market with liquidity. We’ve seen the student loan debt market implode after expanding beyond $1 trillion in outstanding loans, many of which graduates simply cannot afford to repay due to sluggish wages.

Hedge funds and other institutional investors that previously occupied the publicly traded credit arena have moved down the lending spectrum, looking to SMBs and consumer lending as an outlet to generate returns as the domestic Corporate and High-Yield (HY) debt markets are increasingly over-valued, with HY debt trading far above historic norms relative to the associated risk. As a result, competition for borrowers in the private lending arena has skyrocketed. With greater competition comes lenders willing to accept lower interest rates, reduce underwriting standards (with little to no covenants), and chase borrowers who might otherwise be denied due to moderate-to-poor credit ratings (at best). We’re now seeing a similar occurrence in the auto-lending market, which just surpassed $1 trillion in outstanding loans (akin to the student-debt dilemma) to a basket of borrowers whose credit ratings are far from stellar.

After the implementation of Dodd Frank following the 2008/09 financial crisis, regulations limiting commercial bank exposures to “assets” that are essentially bad debts helped remove some of the problems with major bank balance sheets, though derivatives exposures and counterparty risk is still pervasive and poses a serious threat to the system. As an example, global derivatives exposures on a gross basis (not to be confused with net exposure, a metric often misused to measure risk exposure) is greater than 9x global GDP. This clearly reflects a major distortion in the global financial system.

Insolvency issues are on the rise in Europe and Japan as well, and this isn’t the first time either country has seen problems created by major overleverage. Europe and Japan are each uniquely distorted markets, and together reflect the magnitude of the markets’ failure to properly allocate capital.

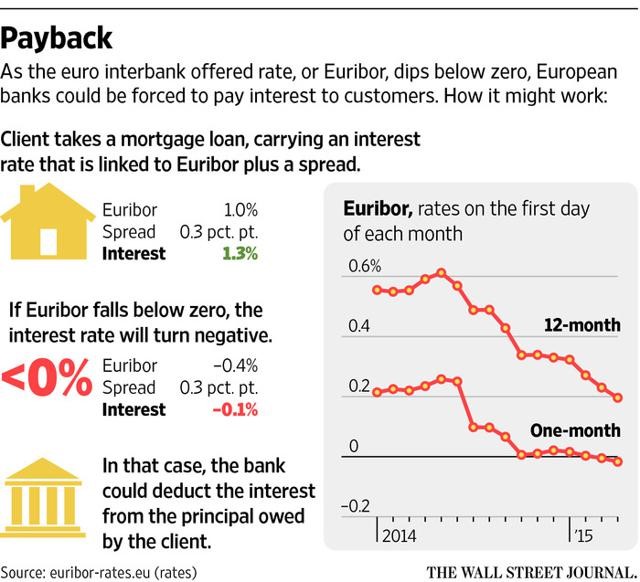

Let’s start with Europe. The ECB, prior to announcing a QE program to buy up ~$1.2 trillion+ of government and private debts, chose to experiment with negative rates. It was the first central bank to venture into this uncharted (and rightfully so) territory, bringing its deposit rate to negative 0.2% in September 2014. This effectively punished the conservative banks for holding decent levels of cash with the central bank instead of extending loans to businesses or to weaker borrowers. Sweden implemented a similar combination of negative rates and bond buying. Denmark pushed rates deeper into negative territory to protect its currency peg to the Euro, and Switzerland moved its deposit rate below zero for the first time since the 1970s. As central banks provide a benchmark for all borrowing costs, negative rates spill-over to a range of fixed income issues. By the end of March of this year, more than a quarter of debt issued by Eurozone governments carried negative yields, meaning investors who hold these positions to maturity will not get all their money back. With the actions of the ECB, many Eurozone banks elected to pass negative rates onto their customers.

Imagine a bank that pays negative interest. In other words, it gets paid to borrow money, and depositors are actually charged to keep their money in an account. Crazy as it sounds, several of Europe’s central banks have cut key interest rates below zero in a bid to reinvigorate an economy with all other options exhausted. No matter how you swing it, this is an unorthodox approach that has created distortions in the financial markets.

Negative interest rates are a sign of desperation, signaling that traditional policy options have proven ineffective, thus new limits must be explored. Despite the obvious artificial inflation that results from such policies, European markets continue to respond positively to these accommodative monetary developments – it’s the new conventional wisdom: When all else fails to trigger growth, create new money and buy bonds.

Did we forget about Basel I-III?

What was the point of the Basel regulations??? It was intended to bring banks across the Eurozone, primarily those in Spain, Portugal, Italy and France, to clean up their balance sheets and stay away from "toxic" corporate risk. As such, the laws limited the amounts of corporate debt these banks could hold on their balance sheets, resulting in banks' offloading these "high-risk" assets, often at fire sale prices (scooped up by private equity/debt players out of the U.S., the U.K. and Europe). Now, all of a sudden it's a positive indicator that European banks have retreated when it comes to standards for credit quality?? It seems logical that this is plan is certain to backfire.

Tumbling rates in Europe have put some banks in an inconceivable position: owing money on loans to borrowers. At least, one Spanish bank, Bankinter SA (OTC:BKNIY), has been paying some of its customers interest on mortgages by deducting that amount from the principal owed by its borrowers (WSJ). This is just one of many challenges caused by interest rates falling below zero (which makes no sense, to start). Throughout Europe, banks are now being compelled to rebuild computer programs, update legal documents and rebuild spreadsheets to account for negative rates. Interest rate have fallen sharply since the ECB introduced measures last year to reduce its deposit rate, and in March launched a new massive QE program targeted at buying public and private bonds to the tune of EUR 1.2 trillion, in EUR 60 billion monthly installments, driving down the yields on Eurozone debt with the intent to foster lending. See the image below depicting how this situation may occur (and is occurring at certain banks), due to Euribor falling into negative territory.

In countries such as Spain, Portugal, and Italy (key countries with undercapitalized bank balance sheets leading up and through the Basel regulations), the base interest rate used for many loans, especially mortgages, is based on a spread over Euribor. As rates have fallen, sometimes below zero, some banks face the paradox of paying interest to those who borrowed money from them.

Yet, the market and the illustrious members of the ECB see loosening lending standards as a positive? Remind us the entire reasoning behind the Basel regulations...

Banks are turning to the central banks for guidance, but what they're receiving is less than comforting.

Portugal's central bank recently ruled its banks would be required to pay interest to borrowers if Euribor plus their stated spread on existing loans falls below zero. Over 90% of the 2.3 million mortgages outstanding in Portugal have variable rates linked to Euribor (WSJ). Most mortgages in the country are linked to a monthly average of three- and six-month Euribor, both of which have been steadily declining and currently hover just above zero.

Additionally, in Spain (another problem area in the European banking system), the vast majority of Spanish home mortgages have rates that rise and fall tied to 12-month Euribor (according to statements issued by Spain's mortgage association). That rate stands at just above zero.

Finally, in the other big country that only recently began to pull itself out of its banking debacle (ITALY), also have about half of their mortgages on variable rates tied to Euribor and existing loan contracts do not stipulate how to proceed in the event Euribor were to fall into negative territory.

Two-month Euribor is at minus 0.072%. Hundreds of thousands of additional loans would be affected if medium-term Euribor rates enter negative territory; the six-month rate currently stands at 0.027% (which represents a rapid decline since the ECB's announcement of negative rates).

Central Bankers and Economists: Losing the Forest from the Trees

A simple, one-month positive data point out of the Eurozone with respect to rising industrial production does not mean the economy is on a rapid upswing out of its troubled position, nor can we say with certainty does the ECB's QE buying have anything to do with it. There are several interacting factors at play here, and monthly output data can be volatile. Interpolating what the ECB might do with its EUR 1.2 trillion QE program due to a single monthly data point is a faulty approach. Europe still has more than its share of structural issues to address to truly become confident about growth over the longer term.

After any given positive data release, economists begin to speculate whether the ECB will begin to signal its satisfaction with this supposed pickup and how this might affect the longevity of its EUR 60 billion (per month) bond buying program, currently slated "at least through September." In turn, this impacts how other central banks respond.

Where Central Banks Should Direct their Focus

Central banks such as the ECB, Japan's BoJ, the UK's BOE and the U.S. Fed should redirect their attention from short-term, often volatile monthly data figures and open their eyes to the obvious, long-term market distortion their actions have created. With repeated communications and actions suggesting markets can simply be manipulated to spur growth through printed money in numerous countries and various global currencies, how long can we rely on the true value of fiat currency? The system has driven itself into believing in its own stability, which in actuality is non-existent.

Groupthink has muddled our views as to how financial markets should behave. A lack of fundamental economic growth, masked by debt-driven financial growth, does not resolve any underlying issues. Instead, unsustainable QE and Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) and the subsequent high (and growing) nominal levels of stock and bond markets have led investors on the hunt for yields, buying assets of increasing levels of risk and ignoring the fact that these assets are often debt-laden and backed by poor or weakening fundamentals.

We need to criticize those who act as Fed proponents, with the only consistent argument being "well, what would you suggest the central banks do?" How about not allowing money to become so cheap that countries and, in some cases, corporations and individuals (as described above in the Eurozone) get paid to borrow. This is simply beyond the realm of sanity, and it puzzles me how many cannot understand this. How about central banks stop reminding the world that they can never run out of money, thus providing an infinite number of excuses to do nothing on the fiscal or structural side. "One should not mistake the wanton creation of money [for] omnipotence" (Anne Stevenson-Yang re the PBOC). This logic could also be applied to the BoJ, the Fed, et al. It's time to return to credible monetary policy that's sustainable over the long term, and pass the ball into the fiscal court. If that means the economy must suffer some dire misfortunes, then so be it. We have created the means for our own demise. From a fellow SA reader's comment (thanks Chrislund):

"Treating the financial system as an endless credit convalescence only leads to capex atrophy. Synthetically low interest rates designed to surrealistically suppress the cost of capital for this many years is a surefire way to institutionalize the misallocation of capital."

Global uncertainty in both the credit and equity markets is rising, and deservedly so. So how do we, as investors or investment managers, avoid following the herd and making investments that clearly have no fundamental basis, without losing out on potential upside as the market’s coalescence of views regarding the new normal continues to persist? Said differently, how do we participate in the upside (as market participants continue to behave irrationally) while protecting our portfolios from massive drawdowns when the chickens come to roost?

One effective approach is to utilize a multi-asset strategy designed to hold equities but also protect the overall portfolio from downside by buying market volatility. This can be executed in several different ways, and one must be careful in doing so to ensure allocation is aligned with risk tolerance. When I refer to “buying market volatility,” I refer to purchasing call options on the volatility index, or the $VIX, such that as global uncertainty continues to rise pending a market implosion, these options climb exponentially in value and thus offset to some extent any losses on long-term equity positions. If one was a complete risk taker with high conviction the heavy levels of market dislocation prevailing today will soon reverse, I could hold no equities positions and simply buy calls on the $VIX, betting that uncertainty will only get worse and thus volatility will continue to rise. As economic fundamentals become increasingly divorced from market behavior and asset valuations, the case for such a strategy becomes incrementally strong.