As I watched the Greek drama unfold, it occurred to me that this episode represents a cautionary tale for the gold standard cheerleaders who would like to return to an era of rigid monetary policy and fixed exchange rates. The modern story of Greece is the tale of a country locked into a currency that it cannot print or devalue.

The Great Depression in Greece

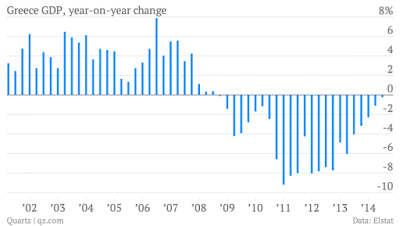

While there are benefits of the gold standard, namely the inability of governments to print money and inflate, the price is a high degree of economic volatility that citizens of developed economies have been unaccustomed to in the last 50 years. An article in Quartz shows that the Greek GDP has tanked so much that it rivals America during the Great Depression:

That collapse in economic output puts the Greek recession right up there with the worst depressions in recent memory. At its trough in the first quarter of 2014—which was revised lower in today’s report—the decline in Greek GDP was roughly 33% from the peak. That’s actually worse than the US peak-to-trough GDP decline of 27% between 1929 and 1933, during the most acute phase of the Great Depression.

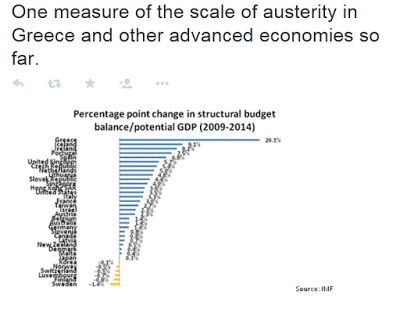

Wow, talk about rigidity and adjustments! For another perspective, RBS) showed the scale of the kind of austerity measures that the Greeks have to endure:

Hope, not despair

The pain has been so great that a number of prominent economists written an open letter in the FT to Greece`s creditors, pleading for "hope not despair":

Sir, The future of the EU is at stake in the negotiations between Greece and its creditor institutions, now close to a climax. To avoid failure, concessions will be needed from both sides. From the EU, forbearance and finance to promote structural reform and economic recovery, and to preserve the integrity of the Eurozone. From Greece, credible commitment to show that, while it is against austerity, it is in favour of reform and wants to play a positive role in the EU.

In a letter to the FT in January, several of us said: "We believe it is important to distinguish austerity from reforms; to condemn austerity does not entail being anti-reform." Six months on, we are dismayed that austerity is undermining Syriza's key reforms, on which EU leaders should surely have been collaborating with the Greek government: most notably to overcome tax evasion and corruption. Austerity drastically reduces revenue from tax reform, and restricts the space for change to make public administration accountable and socially efficient. And the constant concessions required by the government mean that Syriza is in danger of losing political support and thus its ability to carry out a reform programme that will bring Greece out of the crisis. It is wrong to ask Greece to commit itself to an old programme that has demonstrably failed, been rejected by Greek voters, and which large numbers of economists (including ourselves) believe was misguided from the start.

Clearly a revised, longer-term agreement with the creditor institutions is

necessary: otherwise default is inevitable, imposing great risks on the economies of Europe and the world, and even for the European project that the eurozone was supposed to strengthen.

Syriza is the only hope for legitimacy in Greece. Failure to reach a compromise would undermine democracy in and result in much more radical and dysfunctional challenges, fundamentally hostile to the EU.

Consider, on the other hand, a rapid move to a positive programme for recovery in Greece (and in the EU as a whole), using the massive financial strength of the Eurozone to promote investment, rescuing young Europeans from mass unemployment with measures that would increase employment today and growth in the future. This could both transform the economic performance of the EU and make it once more a source of pride for European citizens.

How Greece is treated will send a message to all its eurozone partners. Like the Marshall plan, let it be one of hope not despair.

Tech bubble and the Commercial Crisis of 1847

Still not convinced? Liberty Economics, the blog of the NY Fed, had a fascinating post recounting what happened during the railway tech bubble of 1840s and its aftermath.

British railway mania had a long fuse. The nation went through a lesser, “hypomanic” railway episode in the 1830s, but with the economy weak in the late 1830s and early 1840s, owing partly to the aftermath of the Panic of 1837, the spark did not catch. By 1843, however, the economy was recovering, interest rates were low, railroad construction costs were falling, and railway revenues were rising, thus setting the stage for a full-blown manic episode.

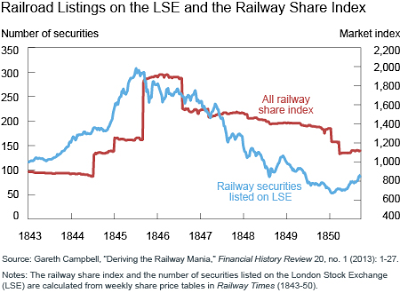

As is usually the case with technology booms, extravagant claims about the transformative powers of the new technology abounded: “Verily railways are the wonder of the world! Nothing during the last few years has created so marvelous a change as the great iron revolution of science” (Evans). Instead of “Internet speed,” as heard during the telecom bubble, the talk then was of “railroad speed.” The growing middle class in Britain, thanks to the industrial revolution, created a larger new cohort of eager investors wanting in on the action. With investors crowding, the number of railroad securities listed on the London exchange—and their prices—roughly tripled between 1843 and 1845 (see chart below).

To make a long story short, the railway bubble ended the same way as the NASDAQ bubble:

The mania, or “collective hallucination,” subsided in late 1845 as expectations seemed to turn, in part because of naysaying by the Economist (founded in 1843) and the London Times. On October 16 of that year, the Bank of England raised discount rates, and as credit tightened, railroad share prices began a long, steep decline, wiping out many fortunes along the way.

That wasn't the end of the story. The effects of the railway crash was exacerbated by a crop failure:

With collapsing railroad prices as background, the proximate cause of the Commercial Crisis of 1847 was the shock to the agricultural sector and the subsequent financial and monetary fallout (Dornbusch and Frenkel). Both Ireland and England suffered massive harvest failures in 1846, which led to food shortages and drove up commodity prices. As food imports from the United States and elsewhere surged, the British trade deficit turned sharply more negative (doubling in absolute terms between 1845 and 1847) and gold bullion reserves drained from the Bank of England to finance food imports. In April, to hoard its dwindling reserves, the Bank raised the discount rate and severely limited the bills it would discount (lend against), causing, as C.N. Ward-Perkins (p.78) mildly put it, “much complaint in financial and commercial circles.”

Aggravating the tightening monetary conditions was a rash of failures of “commercial” firms occasioned by failed speculative plays (via derivatives!) in foodstuffs, particularly corn. With the failed 1846 harvest as prologue, many merchant houses bought corn and other foodstuffs forward, expecting higher prices in the future. By the time these contracts matured in mid-1847, prospects for a strong harvest that summer caused spot prices to fall sharply, catching many speculators short. Further, the Bank of England raised rates again in August, and the confluence of falling prices and higher rates led to widespread financial panic that brought down more than fifty corn merchants in August and September, along with many of the commercial firms that funded their positions. The deflating railway bubble, which bankrupted many enterprises and raised doubts about the stability of the financial system, set the stage for the panic (Dornbusch and Frenkel).

The Bank of England’s ability to respond to the crisis was limited as its hands were tied because the currency was tied to gold. The crisis ended when the Parliament suspended the gold link (emphasis added):

The Bank of England’s ability to contain the crisis as a lender of last resort was severely constrained by the Bank Charter Act of 1844 (Humphrey and Keleher). The Act gave the Bank of England a monopoly on new note (essentially money) issuance but required that all new notes be backed by gold or government debt. The intent, per Currency School doctrine, was to prevent financial crises and inflation by inhibiting currency creation. Adherents recognized that the Act might also limit the central bank’s discretion to manage crises, but they argued that limiting currency creation would prevent financial crises in the first place, thus obviating the need for a lender of last resort. But, of course, not all crises originate in the financial sector. In the case of the Commercial Crisis, the perverse effect of the Act was to cause the Bank to tighten monetary conditions in both April and October as gold reserves drained from the Bank (Dornbusch and Frenkel). In July, a coalition of merchants, bankers, and traders issued a letter against the Bank Charter Act, blaming it for “an extent of monetary pressure, such as is without precedent” (Gregory 1929, quoted in Dornbusch and Frenkel).

The panic culminated in a “Week of Terror,” October 17-23, with multiple banks failing or suspending payments to depositors in the midst of runs. The Royal Bank of Liverpool shuttered its doors on Tuesday, followed by three other banks, and by the end of the week the Bank of England held less than two million pounds in reserve, down from eight million in January. Systemic collapse seemed imminent. On Saturday of that week, London bankers petitioned Parliament to suspend the Bank Act, and by midday Monday it had done so, thus enabling the Bank to issue new notes without gold backing and to “enlarge the amount of their discounts and advances upon approved security” (J. Russell and Charles Wood, Bank of England). The ability to expand fiat note issuance increased liquidity and helped the Bank restore confidence, and the seven percent discount rate the Bank was charging attracted gold reserves back to its vaults (hence the maxim “seven percent will draw gold from the moon”). By December, interest rates were down substantially from their panic levels.

Volatility indeed! The New York Fed then compared the BoE response in 1847 to the Fed response to the Lehman Crisis:

In contrast to the Bank of England in 1847, the Federal Reserve during the Panic of 2007-2008 was authorized to act as lender of last resort, and, in fact, the Fed acted aggressively to provide liquidity to the financial system in unprecedented ways. Through a variety of newly created facilities, the Fed expanded the types of institutions it would lend to, including nonbanks, and the types of collateral it would lend against, including asset-backed securities.

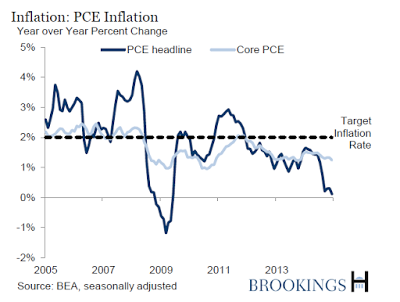

What about the inflation that a gold standard was supposed to prevent? Here is how inflation has behaved after several years of QE and ”money printing” (via the Brookings Institute):

Here is what has happened to inflationary expectations:

So what is more important, an adherence to a rigid ideological dogma, which creates wild and unwanted economic volatility in the form of economic depressions, or a more flexible regime that has resulted in a benign inflationary outlook?

DISCLAIMER: Cam Hui is a portfolio manager at Qwest Investment Fund Management Ltd. ("Qwest"). This article is prepared by Mr. Hui as an outside business activity. As such, Qwest does not review or approve materials presented herein. The opinions and any recommendations expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or recommendations of Qwest.

None of the information or opinions expressed in this blog constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or other instrument. Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and any recommendations that may be contained herein have not been based upon a consideration of the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient. Any purchase or sale activity in any securities or other instrument should be based upon your own analysis and conclusions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Either Qwest or Mr. Hui may hold or control long or short positions in the securities or instruments mentioned.